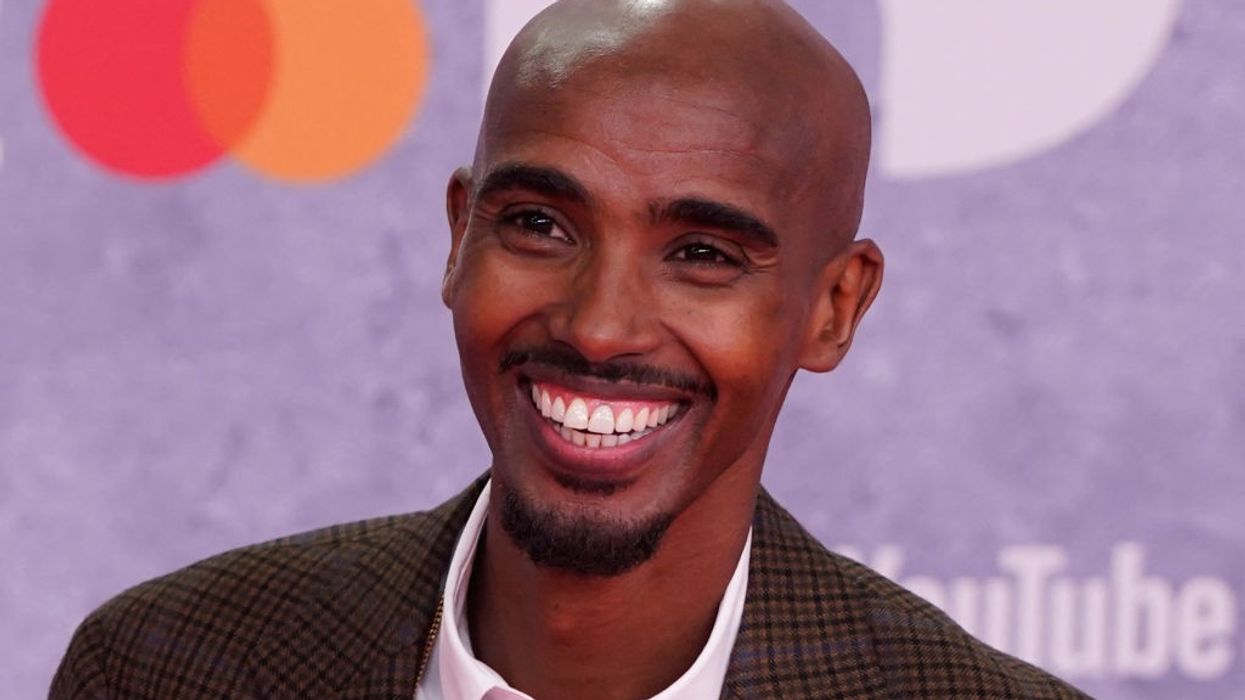

Olympic great Mo Farah won praise from across Britain's political spectrum Tuesday after the shock revelation that he was illegally trafficked as a child to the country and forced to work in domestic servitude.

The 39-year-old distance runner, one of Britain's best-loved and most successful athletes, told a BBC documentary that his real name is Hussein Abdi Kahin.

Rather than moving to the UK as a refugee from Somalia with his parents as previously claimed, Farah said he came from Djibouti aged eight or nine with a woman he had never met, was given a false identity, and then made to look after another family's children.

In fact, he said, his father was killed in civil unrest in Somalia when Farah was aged four and his mother, Aisha, and two brothers live in the breakaway state of Somaliland.

"The truth is I'm not who you think I am," Farah said in the documentary, explaining that his mother wanted him far removed from Somalia's civil wars.

He said his children had encouraged him to tell the truth about his past.

"That's the main reason in telling my story because I want to feel normal, and don't feel like you're holding on to something."

The admission could have raised questions about Farah's UK citizenship, but the interior ministry said he was in the clear.

"No action whatsoever will be taken against Sir Mo and to suggest otherwise is wrong," a Home Office spokesperson told AFP.

The ministry's guidance absolves children of blame if parents or guardians are later found to have obtained their immigration status under false pretences.

'Heartbreaking'

Popularly known as "Sir Mo" after he was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II in 2017, Farah completed the 5,000m and 10,000m double at both the London 2012 and Rio 2016 Olympics.

The London Games in particular catapulted him to stardom in Britain. Finance minister and Conservative leadership candidate Nadhim Zahawi said Farah remained "truly inspirational".

Zahawi, whose Kurdish family fled Iraq for Britain when he was 11, told BBC TV that hearing Farah reveal his life story made him feel "heartbroken, painful".

"All I can say is I salute Mo Farah," he said.

Lisa Nandy, a senior member of the opposition Labour party, said Farah's decision to speak out could be a "gamechanger" for other victims of trafficking.

"I spent a decade working with children who were trafficked to the UK and everything about this is heartbreaking," Nandy tweeted.

London's Labour mayor Sadiq Khan said: "Everything Sir Mo has survived proves he's not only one of our greatest Olympians but a truly great Briton."

"We must build a future where these tragic events are never repeated," he added, at a time when the UK government is trying to send asylum claimants to Rwanda under a scheme to deter cross-Channel migrants.

'Get out and run'

Farah's wife Tania said in the year leading up to their 2010 wedding she realised "there were lots of missing pieces to his story" but she eventually "wore him down with the questioning".

When he arrived in the UK, Farah said the woman who accompanied him took a piece of paper from him that had his relatives' contact details and "ripped it up and put it in the bin".

"At that moment, I knew I was in trouble," he recalled.

Farah said he was forced to do housework and childcare "if I wanted food in my mouth", and was told: "If you ever want to see your family again, don't say anything."

"Often, I would just lock myself in the bathroom and cry," he says in the documentary.

His life was transformed for the better when he went to live with Kinsi Farah, the sister-in-law of the woman who is alleged to have brought him to England.

He started regular schooling and Farah's physical education teacher, Alan Watkinson, noticed how the troubled youngster's mood changed when he was on the running track.

"The only language he seemed to understand was the language of PE and sport," says Watkinson.

Farah eventually told Watkinson the truth about his status, and the teacher informed social services.

It was Watkinson who applied for Farah's British citizenship, which he described as a "long process" that finally reached fruition in July 2000.

Farah revealed in the programme that he had since spoken to his now namesake and said he was "proud" he knows what he has achieved.

(AFP)