CHARRED walls, collapsed tin roofs and smashed windows in a burned Kuki community church illustrate how deadly ethnic violence has led to brutal sectarian attacks in India’s troubled Manipur state.

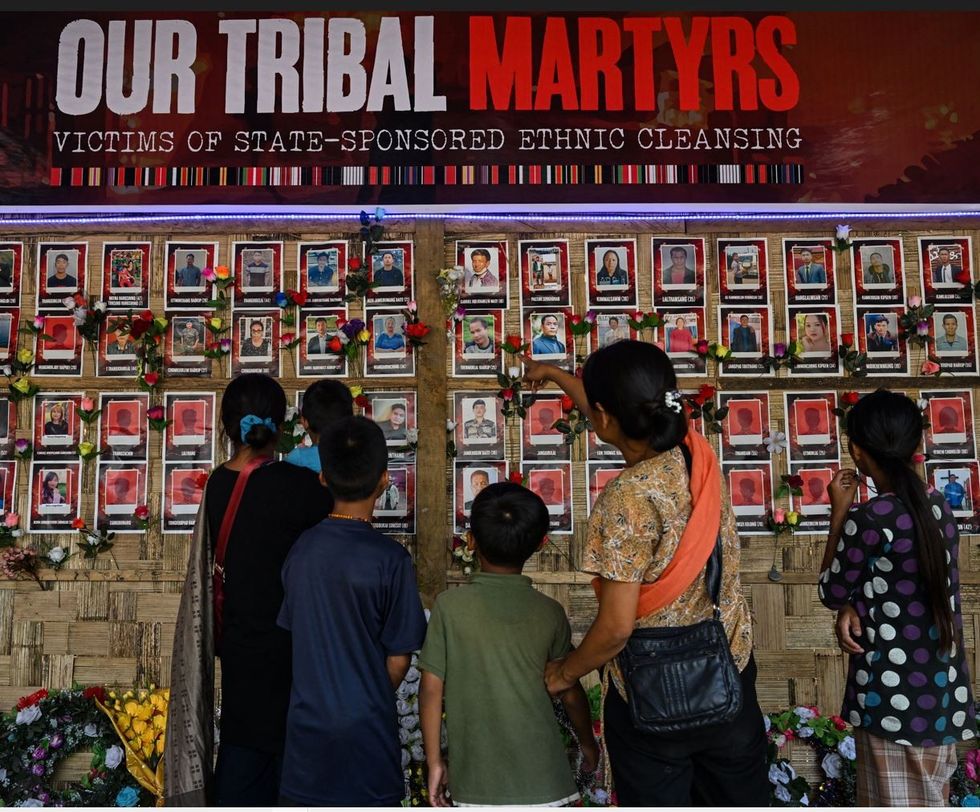

At least 120 people have been killed since May in armed clashes between the predominantly Hindu Meitei majority and the mainly Christian Kuki in the northeastern state.

Many in Manipur believe the number could be higher.

The bitter fighting has lasted for almost three months, a deep embarrassment for India’s prime minister Narendra Modi as he prepares to host a summit of G20 leaders in September and contest a general election next year.

Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) also heads the state government in Manipur.

Street protests spiralled into armed conflict and now, rival gunmen have dug into bunkers and outposts along the highway and in other places in Manipur. They regularly fire at each other with assault weapons, sniper rifles and pistols.

Tens of thousands of people have fled their homes because of the fighting, villages have been set on fire and many women sexually assaulted, residents and media reports say. The Meitei-dominated state police are seen as partisan, while army troops have been ordered to keep the peace but not to disarm fighters. There is no sign of any early resolution.

Historian and author Ramachandra Guha said the situation was “a mixture of anarchy and civil war and a complete breakdown of the state administration”.

“It is a failure of the prime minister at a time of grave national crisis,” Guha added, speaking in a TV interview. “Narendra Modi lives in a bubble of his own, he does not like to be associated with bad news and somehow hopes he will ride it out.”

The prime minister’s office and a state government spokesman did not respond to requests for comment.

Kukis make up around 16 per cent of Manipur’s roughly 2.8 million people, according to India’s last census in 2011. However, their demands for a separate state administration for them are rejected outright by the Meitei, who form more than half of the population.

Conflict erupted from a mix of causes including competition for land and public jobs, with rights activists accusing local leaders of exacerbating ethnic divisions for political gain.

The politicians deny that, but months into the crisis, divisions are hardening into bitter cycles of revenge attacks that have included killings and the burning of homes, Christian churches and Hindu temples. The rivals have formed militia forces who insist they will not be laying down their guns any time soon.

Much of the violence and killings have taken place in buffer zones near Manipur’s foothills where intense gun battles erupt regularly, security officials said.

The stretch of the national highway where the Meitei-dominated Bishnupur district meets Kuki-controlled Churachandpur is one of the zones that has seen some of the worst fighting.

According to government estimates, 2,780 weapons stolen from the state armoury, including assault rifles, sniper guns and pistols, remain with the Meiteis, while the Kukis have 156.

Kae Haopu Gangte, the general secretary of the Kuki Inpi Manipur, an umbrella Kuki civil society group, blamed the conflict on what he said was the desire of the Meiteis to dominate Kuki land.

The Kukis now want a separate state within India, he said.

“Until and unless we achieve statehood we will not stop,” Gangte said. “We are fighting not only Meiteis, we are fighting the government.”

Pramot Singh, founder of Meitei Leepun, a prominent Meitei organisation that has members on the frontlines, said all Meiteis supported the conflict.

Three months ago, 16-year-old Paominthang was a student from the farming Kuki people who dreamed of being a football star. Now he is armed with a .303 rifle and said he is ready to kill rival Meitei community fighters if needed.

Paominthang, who gave only one name for fear of reprisal, said he abandoned his books after a Meitei mob attacked his family. “They burnt down my house – I had no other choice,” he said, cradling his gun and insisting he had no qualms about using it in defence. “I will shoot.”

His base, dubbed ‘Tiger Camp’, is reachable via a thin path up steep and lush hills. Similar camps run by rival forces are dotted across the area.

In militia camps in both Kuki and Meitei areas, reporters saw men armed with an array of sophisticated weapons, including Kalashnikov assault rifles and homemade guns crafted out of metal pipes.

“We can’t show you, but we have ammunition that can last for more than two months,” claimed Phaokosat Hokip, 32, a Kuki fighter, who in May worked for an aid agency.

Hokip’s group conduct dusk-till-dawn sentry duty from their sandbagged post, staring into the dark using high-powered binoculars, with other militia members resting in shelters made of plastic sheeting attached to bamboo poles.

“If we are not here with guns, they will turn up in thousands and burn down our houses,” Hokip said.

Across the divide, in the Meitei camp, gunmen say they are fearful of the Kuki. “Even the state forces are not able to control it,” said KB, a 55-year-old Meitei who spoke on condition of anonymity. “It is a civil war.”

The Meitei people have long accused the Kuki of supporting undocumented immigrants from Myanmar and poppy cultivation, claims the Kuki deny.

“We used to live together,” added KB. “Suddenly, they attacked us, and now want a separate administration – that will not happen”.

India’s home minister Amit Shah has promised an “impartial investigation” into the violence and has said the government “stands shoulder-to-shoulder with the people of Manipur”.

DS Hooda, a retired Indian general who served in Manipur, said the government had to tackle the crisis in “a nonpartisan manner”.

“If civilian vigilante groups are going to take up weapons to protect themselves, it is a sad commentary on the authority of the state,” he said. (Agencies).