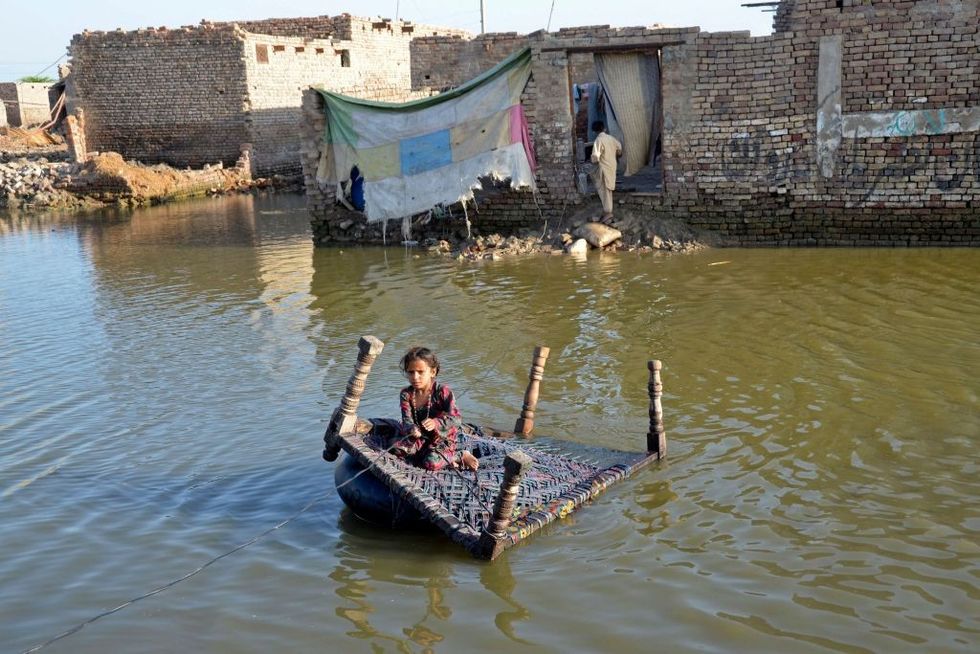

The devastating floods that affected lives and economy in the South Asian nation of Pakistan this year have rung the warning bells across the globe. Environmentalists and conservationists have raised serious concerns over the deadly disaster that has killed nearly 1,700 people and displaced almost eight million people.

The extreme environmental conditions in Pakistan, which also experienced heatwaves besides the floods, are being seen as a new normal not only for that country but overall for South Asia.

Chatham House, an independent policy institute in London, recently came out with a study explaining how the impacts of climate change in South Asia, one of the most populous regions in the world, can witness knock-on effects that go beyond borders and adversely influence other areas such as trade, security, financial markets, and migration.

The study also explored how nations in South Asia can join hands to address these pressing issues and the innovative solutions that can be identified to improve resilience.

Pakistani prime minister Shehbaz Sharif recently gave an emotive address at the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, where he said that despite its low carbon footprint, Pakistan became a victim of something with which it had nothing to do.

But the challenges posed by climate change are universal. Growing greenhouse gas emissions are causing extreme weather events across South Asia and the world.

South Asia one of the most vulnerable regions to climate change

According to the Chatham report, South Asia is one of the most vulnerable regions to climate change with more than half of all people in the region having been affected by at least one climate-related disaster in the last two decades. The year 2022 saw an early, and prolonged, heatwave in India and Pakistan which led to subsequent flooding in wide swathes of Pakistan as well as parts of India and Bangladesh.

These events appear to present a sample of the ‘new climate normal’ in the region. According to the World Bank, more than 800 million people across South Asia are living in climate hotspots.

South Asia is already struggling with several challenges in the form of poverty, high inflation, slow economic growth, and climate change. The region's youthful population also presents a source of optimism and there is a potential for growth, particularly regarding investment in climate resilience and adaptation.

Therefore, if the region fails to deal with the climate change threat successfully, the consequences will be global and hence, finding an effective response to the threat should be viewed as global public good, the Chatham report added.

In March 2022, Pakistan, along with its eastern neighbour Pakistan, faced a heatwave well before the usual months when the summer peaks. While India recorded its hottest March since 1901, temperatures peaked at close to 50 degrees Celsius in the Pakistani city of Nawabshah.

Another Pakistani city Jacobabad recorded the hottest temperature, 51 degrees, in May.The heatwave was one of the longest for decades and a late, and incessant, monsoon followed it, resulting in the massive flooding in Pakistan. The two events are connected, the report said.

"Extreme heat increases the risk of subsequent flooding because warmer air can hold more moisture, drier ground is less able to absorb rainfall and, for countries in South Asia, hotter weather in the Himalayas brings the risk of increased glacial melt," the Chatham report said.

The consequences of the extreme events were exacerbated by two unconnected phenomena -- the Covid-19 pandemic and Russia's invasion of Ukraine. While the first affected availability of agricultural labour, the second saw a rise in fuel and food prices.

It is not that countries of South Asia had seen riverine flooding for the first time as swollen rivers burst their banks during the monsoon. But the 2022 floods in Pakistan were an order of magnitude which was different from the past, stemming from intense downpour, including in areas that do not see heavy rainfall.

Heatwave, flooding effects cascade across gepgraphies

The twin events of heatwave and flooding had effects that cascaded across sectors and geographies because of several inter-dependencies. They are both direct and indirect and show the manner in which the challenges are inter-linked. According to the World Bank, they threaten ‘Pakistan’s development ambitions and its ability to reduce poverty. The country needs fundamental shifts in its development path and policies, requiring substantial investments in people-centric climate adaptation and resilience, that will require international support'.

Direct consequences of extreme weather include heat waves leading to increased forest fires, for instance, or flooding destroying infrastructure, eroding riverbanks, saline intrusion and the destruction of buildings and crops. The heatwave in the breadbasket of South Asia – Pakistan and northwest India – was particularly harmful for the wheat crop.

The indirect consequences range from migration within, and between, countries, food insecurity, health risks and disruption to trade and finance. While the means by which societies can become more resilient to the direct impacts are relatively well-established – if often politically difficult – resilience needs to be extended downstream into the indirect threats.Extreme heat has also had bigger environmental, economic and social ramifications across the region.

Between 2017 and 2021, the damage caused by wildfires in India's Himalayan state of Uttarakhand more than trbled, while between November 2021 and June 2022, the state recorded almost 13,000 wildfires.

The most immediate economic impact from heatwaves is a rise in demand for power for cooling which has put a massive load on power grids across the region and led to power outages. To counter them, India has tried to ramp up electricity generation using coal-fired power stations.

While demand for power has gone up, that for most goods have fallen, and productivity has been lower.

India alone, by some estimates, suffers half the 200 billion days of labour lost globally owing to heatwaves. This could account for up to 4.5 per cent of the country's GDP by 2030, while its neighbours Pakistan and Bangladesh could see losses of five per cent of GDP due to lost labour.

The impact is worse for informal workers and those who work outdoors in sectors such as construction, transport and agriculture. But cooling is something which goes beyond the individual. Some medicines and food products also require cooling. Currently, less than four per cent of fresh produce in India is transported by cold-chain logistics (keeping foodstuffs cool along the supply chain), the report said.

While South Asia has a huge potential market for cold-chain technology, there would be major implications for energy demand if it were to develop. Demand for air-conditioning is rising fast as access to energy increases but from a low base.In 2019, one study suggested just 10 per cent of India’s population had an air-conditioning unit.

The massive untapped market offers business opportunities – by some estimates up to $1.5 trillion by 2040 in India alone – but also points out the need for a significant rise in energy production and/or the development of fresh cooling technologies.Investment in sustainable cooling solutions will be crucial to a just and equitable energy transition.A number of surveys in Bangladesh have suggested that the vast majority of people who move into urban areas cite environmental reasons for their movement, including erosion, flooding, and cyclones.

Those who move into slums are frequently the worst affected by extreme weather due to over-crowded spaces with less green space and less access to cooling technology.

BRAC, an international development organisation from Bangladesh, has partnered with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to develop the Climate Resilience Early Warning System Network (CREWSnet) to forecast the community-level impacts of climate change in the country.

By fusing climate science with development programming, BRAC can use this tool for informed decision-making.

For example, BRAC can identify when a heatwave will become particularly severe, or which communities will need to be evacuated during a cyclone, and provide the necessary knowledge and resources to strengthen affected communities’ abilities to respond, and adapt, to future extreme weather or climate impacts.

Historically, migration provided one means of dealing with environmental degradation, and cities in South Asia continue to expand because of rural challenges. The abandoned Moghul capital of Fatehpur Sikri in north India proves that cities require a perennial water supply. But, in contemporary South Asia, the scope for mass migration within the region is less apparent and those areas with the prerequisites for urbanisation are largely already built upon.

Scientists predict that this extreme weather phenomenon, in particular ‘urban heat islands’ where 45 degree temperatures feel like 50 degrees, will become more frequent and severe.Yet, while these impacts have generated understandable anger among politicians in South Asia, it seems they have neither generated widespread public demand for action nor concrete actions to prioritise climate action.

Rather, the greater the frequency of extreme weather events becomes, the greater becomes the ambivalence towards them. While nations such as Pakistan highlight their lack of responsibility for climate change, yet their vulnerability to its effects; for many this emphasis on vulnerability provides an excuse for inaction.Every country in South Asia has a national level policy or plan to deal with the impacts of climate change. But, while implementation of those plans is less apparent, the capacity to implement plans at a local level differs dramatically.

Some are even close to non-existence. While solutions to the specific impacts of climate change such as extreme rainfall and heatwave are largely known and often simple in theory, they are sometimes harder to implement in practice. Increasing vegetation in cities, for example, is one way of dealing with the urban heat island effect. Vegetation reflects, rather than absorbs, sunlight and plants release moisture helping lower temperatures.

As part of the Cooling Singapore project, for instance, 56 per cent of the island has been lined with shady Angsana and rain trees to reduce heat and improve outdoor thermal comfort. The construction of more green public spaces, such as parks or playgrounds, would also serve to absorb heat and allow better circulation of air. The Dhaka North City Corporation is an admirable example whereby 20 parks and playgrounds are being developed through the greening of urban open spaces. A less costly alternative would be the construction of rooftop gardens.

Traditional roofs absorb heat while heating the building below. By reflecting heat, rooftop gardens could serve to lower the cost of air conditioning, and of heating in colder months. Depending on the plants grown, additional benefits could be to filter pollutants, provide food or increase biodiversity. An alternative to rooftop gardens is to simply paint roofs white so they reflect rather than absorb heat. Various pilot projects in India have seen that this reduces indoor temperature and also helps in bringing down the demand for power.

Need for regional engagement

The starting point for regional engagement in relation to disasters, particularly in regions with concerns regarding sovereignty and political tensions, has generally been through meteorological information-sharing and the development of early warning systems.

For riverine floods, in particular, data held by upstream countries can warn those downstream of impending threats though sensitivities between upstream and downstream riparians regarding river-flows can stymie efforts towards information-sharing.

There are several arguments to justify greater cooperation across South Asia, including between India and Pakistan. One is that in the absence of cooperation, climate change will serve to heighten tension, in particular, over shared rivers. Another argument is that there is scope for mutual benefit from early-warning systems and information-sharing along with learning from examples of best practices.

Finally, because the challenges are shared, so too are countries’ interests. Engaging regionally and forging joint positions in international forums, most obviously the Conference of the Parties (COP), would amplify their voices. This is particularly the case where India and Pakistan need to stand together on climate-change related issues despite their other political differences.