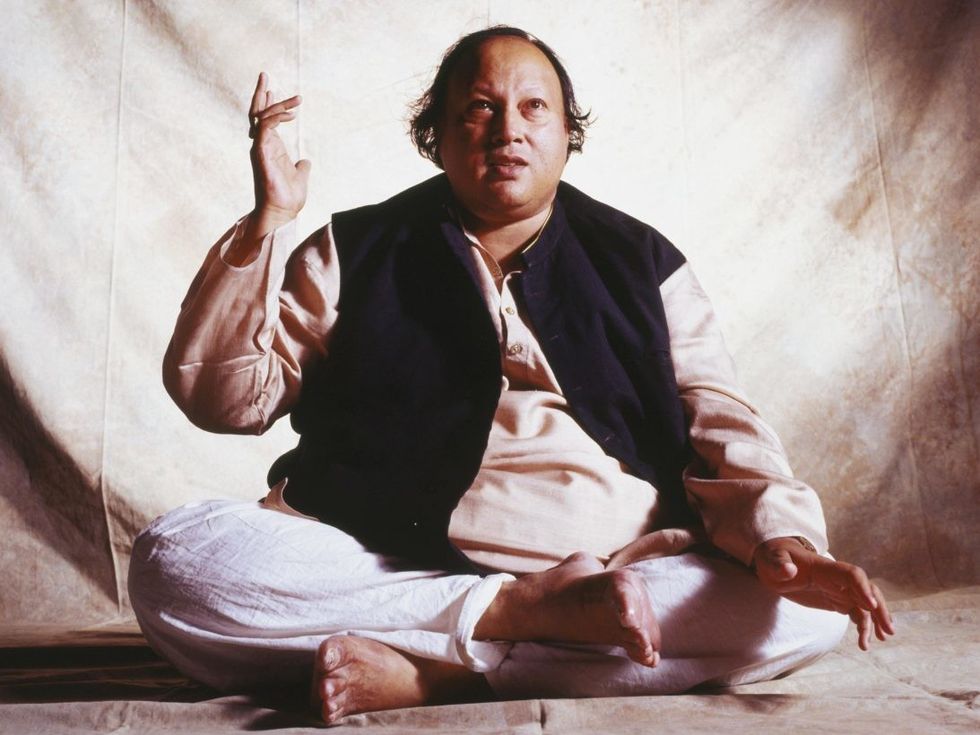

THE late great singer Ustad Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan took qawwali to unimaginable heights before he prematurely passed away aged 48 in 1997.

After his death, there was a void that had to be filled. His nephews, Rizwan and Muazzam, headed a qawwali group that should have been the natural successor – they took the same starmaking steps as Nusrat with a performance at Womad festival, along with getting the influential record label Real World to sign them up. Despite being truly talented, the young maestros were thrown into the deep end too early and were not able to capitalise on those early breaks.

Meanwhile, Rahat Fateh Ali Khan, who had been performing with Nusrat since a teenager, saw himself as a natural successor. But, he struggled to make a mark, despite working with many of his late uncle’s group members.

Rahat would regularly perform concerts at smaller venues for negligible remuneration.

Then, one day, his career changed course when actress turned film producer Pooja Bhatt signed him to sing for her directorial debut Paap in 2003.

This was followed by her father, Mahesh Bhatt, giving him the chance to sing the super-hit song Jiya Dhadak Dhadak for his film Kalyug two years later.

After that there was no looking back, as he became hot property in Hindi cinema and delivered a string of successful songs. Bollywood raising his profile saw him performing at prestigious venues.

He then teamed up with big-thinking promotor Salman Ahmed and went from performing to relatively small crowds to delivering sold-out shows at arenas around the world. Even when Bollywood put a ban on Pakistani singers, he still had enough songs to sell out shows globally. The singer who once performed for a few thousand pounds became a multi-millionaire.

Despite the presence of more talented qawwali singers, the global fame meant he became the natural successor to his late uncle Nusrat despite having just a fraction of his creative ability. What most people didn’t see, and some only got glimpses of, was the dark side to the singer’s personality.

I remember going to see him at a major Pakistani concert at Wembley arena and subsequently writing about how he seemed to be clearly intoxicated on stage. He struggled to mime to his own song and slurred his words. Within music and media circles there was always talk about his heavy consumption of alcohol. Then, with the advent of social media, people started getting glimpses of him being allegedly intoxicated via embarrassing videos.

A basic online search using the query ‘Rahat Fateh Ali Khan drunk’ will reveal numerous videos and news articles depicting him in an alleged intoxicated state. In Islam, alcohol is strictly prohibited, especially for Sufi singers due to their spiritual practices.

Thus, his alleged regular consumption of alcohol brought disgrace to the esteemed reputation of his uncle, whom he was expected to succeed as the heir apparent, as well as to his family’s musical lineage spanning centuries.

This leads to what happened recently. Shortly after announcing he was terminating a long-term partnership with his international tour manager, another embarrassing video went viral on social media, where he can be seen beating up a staff member for losing a ‘bottle’. It was widely reported that he was drunk and angry that his liquor had been misplaced. Those who listen to the way his words are slurred in the video would likely agree.

Rahat then shared a video with the man he was shown beating and denied all the allegations. He gave the most laughable explanation about the bottle in the video being spiritual water and said he had apologised to the man whom he had assaulted. The staff member backed up the account.

But it was hard to find anyone who believed him and not surprisingly, he was once again heavily trolled. After realising his explanation was utterly ridiculous, Rahat released another video where he asked for forgiveness from everyone, including his fans, family, god, and females he had worked with, for any bad behaviour. He promised to never put himself in such compromising situations again. The apology was undone, however, with him admitting that more embarrassing videos from the past might turn up. Pakistan’s Federal Investigation Agency has also reportedly initiated a money-laundering and tax evasion inquiry against him.

What has been clear is that Rahat Fateh Ali Khan has balanced his talent, stardom, and opportunities with shameful behaviour on a regular basis. His illustrious uncle has never faced accusations of being in a drunken rage, assaulting staff members, performing intoxicated on stage, or undergoing investigation for serious tax evasion and money laundering.

However, a Google search reveals that Rahat has consistently been the target of such damaging allegations.

Those who believe there is no smoke without fire, will agree that he doesn’t deserve to wear the crown of Ustad Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. He has regularly shamed himself and his family that has proudly carried the torch of spiritual Sufi music across different generations.

Him promising to do better, won’t undo shameful behaviour that has lasted so many years.