NOTEWORTHY among the dazzling new crop of Asian crime writers is Ram Murali, who has come up with Death in the Air, a remarkably clever murder mystery (where it’s difficult to guess the identity of the killer).

Among crime writers, Abir Mukherjee and Vaseem Khan are now established names. In fact, the latter was elected chairman of the Crime Writers’ Association in 2023.

This year has belonged to AA Dhand, one of whose crime novels set in Bradford has been turned into a six-part TV series, Virdee, by the BBC. Another author showing promise is Atima Srivastava.

Murali’s novel is set in Samsara, a world-class hotel spa in Rishikesh in the Himalayas.

His central character is Ro Krishna, whose family come from Tamil Nadu. He has easy charm and an Oxford education behind him, but he has come to Samsara to decide what to do next in life, since he was forced out of his last job by a woman described as a “latrine with a face”.

There are other characters – Indian, American and British– who gather at Samsara, which is owned by a Mrs Banerjee. The resident yoga teacher is Fairuza. Sanjay Mehta is a not very nice Indian politician. Ro appears destined to have an affair with a ravishing Bengali beauty, Amrita Dey, who has turquoise-coloured eyes. But, alas, she turns out to be the first murder victim. Ro becomes a sort of assistant to an Inspector Singh, who takes charge of the investigation.

There is a feel of an Agatha Christie thriller about Death in the Air. In fact, her 1935 novel, Death in the Clouds, about murder on an aeroplane, had been published originally as Death in the Air.

It turns out Murali is a devotee of the “Queen of Crime” and has scattered Christie references and clues through his novel as though he was organising a treasure hunt for the reader.

He told Eastern Eye: “I’ve probably read every Agatha Christie book five times, and I probably read them all three times by the age of 15. She’s like a deity to me. She’s the best-selling fiction writer ever in the English language, but I don’t think she gets enough credit for the quality of her writing. She was a huge influence on me as I was writing the book. It’s filled with secret Agatha Christie jokes.”

Murali said he loves Conan Doyle as well – “one of my first memories is my father reading me The Hound of the Baskervilles”.

His favourite authors also include John Buchan and Somerset Maugham, as well as the writer Hector Hugh Munro, who was better known as Saki.

But if he were ever on Desert Island Discs, “I would say that I’m not taking Shakespeare, but the classic works of Agatha Christie instead. I can read Agatha Christie over and over and over again. I probably read at least some Agatha Christie every week.”

He does not consider himself to be a professional writer and reveals Death in the Air came about almost by accident. “I never wanted to be a writer, at all. I never wrote a word of fiction until I wrote this book. It was not a dream of mine. But I have always been a reader. I probably read almost a book a day.

“Just before the pandemic, in Christmas 2019 I had left my last job and was taking time to figure out what to do next. I ended up at a hotel called Ananda in Rishikesh, just like Samsara. And while I was there, I kept thinking, well, this would be such a great place for an Agatha Christie-style murder mystery, but I’d never written in my life.

“For the first time in my life, I started taking random notes. And actually, almost all the characters in the book are based on people I saw there.” When he imagined the character of the yoga teacher Fairuza, the plot fell into place. In the summer of 2021, he rented a cottage in Scotland. His 100-page outline became the manuscript. He found an agent the following April and the book “sold to HarperCollins in the US a year and a week after I started writing. I was very lucky. It has been published by Atlantic in the UK and Penguin in India”.

He has his own ideas about how a murder mystery should end. “To be honest, I think a lot of crime writers want everything sort of tied up at the end and feel like there was justice.

But I don’t know. I think one of the points of my book was there’s more than one kind of justice.” He said the story of Ro Krishna, “is very similar to mine. My family’s from Tamil Nadu. My parents came to the UK to study. They are both doctors who lived in Scotland for a very long time. My sister was born in Scotland. Then my father went to New York for a fellowship, and I was born there (in 1978). They never left. I grew up in New York.”

His parents now live in California, but London has been Murali’s home for the past seven years. Prior to that, he lived in Paris for 15 years. He first attended Dartmouth College, an Ivy league institution in New Hampshire in the US. He said: “I then did a master’s at the LSE in London, then went to Law School in Columbia. Then I did a LLM in commercial law at Queens’ College, Cambridge (where he got a First).”

As a lawyer in private practice in London and Paris, his CV says he worked for many years across all aspects of film and TV development, production and distribution.

Death in the Air is written in a deceptively simple style, but that disguises its depth and subtleties. He said: “I wanted the book to be very accessible. I wanted this to be a book that an 11-year-old could read, but then maybe read it again when they are 25 and find it completely different.“There’s not a single obscenity in the book, which was one of the first choices I made as I started writing it, because the book is dedicated to my grandmother. And it’s a love letter to Agatha Christie, so I wanted it to be a book that the two of them could have read and not found distasteful. The book was going to be very chaste, because also I was always thinking about India. I wanted it to be a book that Indian people could appreciate. I wanted it to be a book that my parents could read and send to their friends.”

Murali added: “Maybe my biggest motivation in writing the book was to make India look glamorous and desirable and alluring as a place. My father always says that the west is obsessed with making India look dirty and poor and filthy. I wanted to write something very different.

“Really, for me, the core of the book was I wanted to tell the story of reconnecting to your ancestors, and talk about the cost of immigration and being uprooted from your past and from your ancestors and where they lived.

“Every person in the last 1,000 years of my family on both sides probably was born within the same 500-square-mile part of India. And so what does that mean when you’re the first person not to have been born there?

“That territory has obviously been covered in books like The Namesake by Jhumpa Lahiri. But I wanted to write that in an entertaining way. I wrote a murder mystery because I wanted to make it fun. But those were the themes I really wanted to explore.”

Death in the Air by Ram Murali has been published by Atlantic Books. £16.99

His memoir

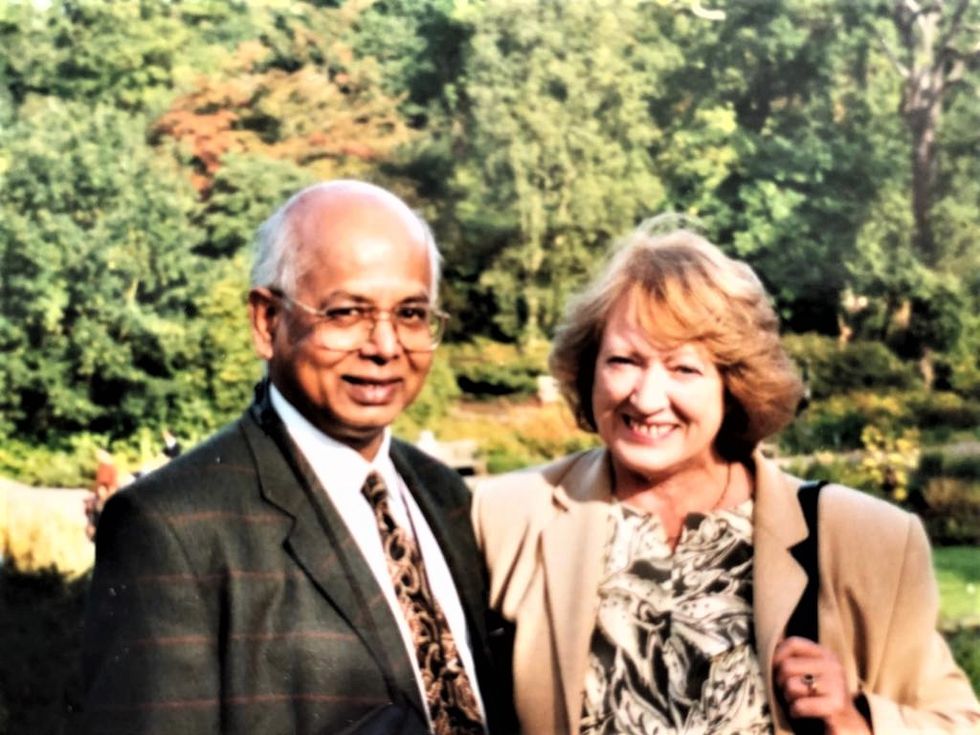

His memoir His parents Dr Pankaj and Enid Basu

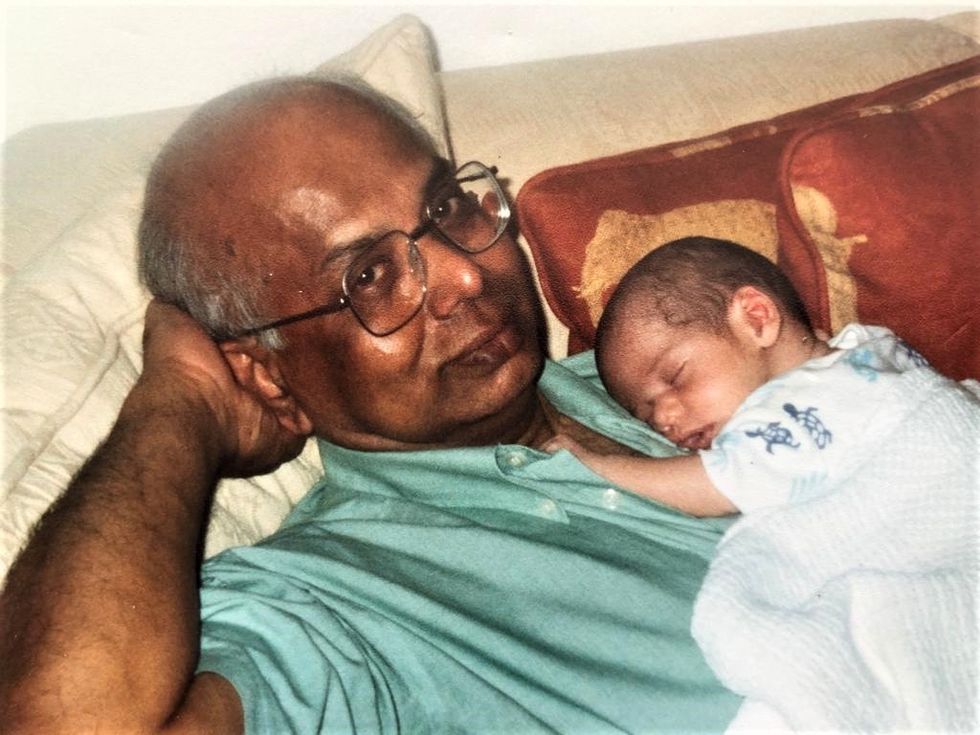

His parents Dr Pankaj and Enid Basu Dr Basu as a grandfather

Dr Basu as a grandfather

Her new novel

Her new novel Her cottage in Glengarriff

Her cottage in Glengarriff The view of the Caha mountains

The view of the Caha mountains

'The Guilt Pill' her latest booksaumyadave.com

'The Guilt Pill' her latest booksaumyadave.com