PLAY SET IN THATCHER ERA EXPLORES TENSION BETWEEN OPPOSING POLITICAL VIEWS

by AMIT ROY

WITH so much poison currently circulating at Westminster, you do wonder what happens especially to male MPs when they go home to their wives.

What if a Brextremist has a remain-leaning wife or possibly the other way round? Jo Johnson’s resignation from his elder brother Boris Johnson’s government indicates blood is thicker than water – but only up to a point. Brexit is certainly taking its toll on family life.

But Hansard, a new play at the National Theatre, directed by Simon Godwin and written by Simon Woods, is not about the consequences of Brexit, despite its name. After all, Hansard is the name given to transcripts of the day-to-day parliamentary exchanges that take place in the Commons and the Lords.

However, Conservative MP, Robin Hesketh, played by Alex Jennings, and his wife of 30 years, Diana, portrayed by Lindsay Duncan – their acting is very persuasive – argue with each other as though they were in the Commons. There seems to be little love between them.

The play is set in 1988 when Margaret Thatcher was prime minister. Robin, a junior minister, has supported passage of the Local Government Act 1988 which contained the controversial clause 28. Basically, this made it illegal for local authorities or schools to promote homosexuality. His wife, however, is a left-leaning woman with views diametrically opposed to those of her husband.

It is only towards the end of 90-minute piece that the dark secret in the lives of the Heskeths comes to light. That is probably the best bit of the play.

Hansard begins with an emotionally and physically drained Robin returning to his Cotswolds home. It is nearly midday, but he finds Diana lounging around in her dressing gown and he discovers an empty gin bottle in the bin.

“And the Dubonnet too – my God!” he says. “Denis Thatcher has nothing on you.”

The couple are expecting friends to lunch, but the fridge is bare. Diana has not bothered to get in any food.

Later, Robin chastises Diana for not being able to manage lunch: “And nobody else has to put up with this sort of performance. Do they? Even the Tebbits can manage a Sunday lunch, and she’s paralysed from the neck down. If I did murder you, I’d bring this up as a mitigating circumstance.”

Perhaps Woods might want to reconsider this unkind reference to the Tebbits.

The back and forth between Robin and Diana delves into some of the political issues of the day. By and by, the exchanges get increasingly bitter.

Robin admits the great offices of state have eluded him: “Here I am – cursed with emotional intelligence.”

Diana offers another explanation: “I thought you hadn’t made it to the top because you didn’t have the right sort of wife.”

“Nobody thinks that,” her husband assures her.

“Of course, they do,” she insists.

Robin wasn’t being kind: “No, they don’t think you’re left-wing, darling. They think you’re highly strung.”

He absolutely refuses to watch cinefilm of their son Tim cartwheeling. The reason will be revealed towards the end.

She has a withering assessment of Robin’s Eton education: “That’s the trouble with the class system, isn’t it? So easy to mistake an expensive education for an actual understanding of the world.”

He says he would like a minimum level of support from her: “I’m not asking for the full Norma Major.”

Diana berates her husband for not reading a novel: “When did you last read a novel?”

When he points out “I read that Jeffrey Archer over Easter,” she responds dismissively, “Jeffrey Archer doesn’t count.”

It so happened that on the night I went, Lord Archer was in the audience, having that very day released his latest novel, Nothing Ventured. In fact, we chatted for a while. Charming man, and one of the most successful authors in the world. There’s nothing to be snide about.

Diana suggests that Robin should distribute Margaret Drabble or Doris Lessing to his ministerial colleagues, “even slip Virginia Woolf into Margaret’s box. That’ll shake her up. Take Margaret to Hedda Gabbler – could change the whole course of British history.”

He has had enough: “These liberal-arts people, with their jumpers and their beards and their profound moments of epiphany, who don’t have a clue about running the country, and yet somehow because they’ve read the latest Ian McKellan novel, they think they can look down on those of us who are doing these appalling, oppressive things like worrying about employment figures and exchange rates and whether the pension funds have any bloody money in them!”

Robin sneers at his wife: “You’ve been at the Guardian again, haven’t you? It’s why I keep telling them in the village shop not to sell it to you. Terrifying combination of righteous indignation and typographical inaccuracy.”

Truce is declared when husband and wife finally confront the truth about their son, but that is a spoiler and should not be given away.

Hansard is the National’s Lyttelton theatre, London, until November 25.

Khaled Hosseini

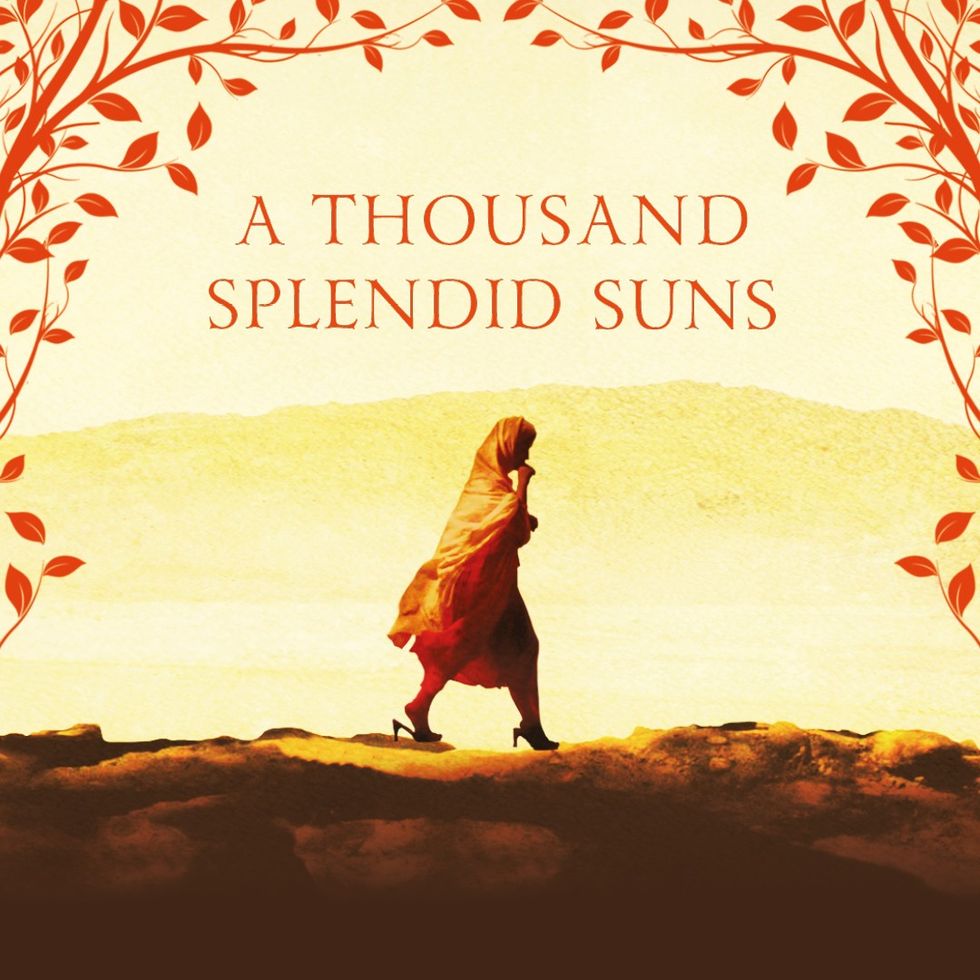

Khaled Hosseini The poster of the stage adaptation

The poster of the stage adaptation

Mrunal Thakur in Sita Ramam

Mrunal Thakur in Sita Ramam  Director Anjali Menon

Director Anjali Menon Actress Nayanthara

Actress Nayanthara

Seated Jain enlightened teacher meditating, about 1150-1200The Trustees of the British Museum

Seated Jain enlightened teacher meditating, about 1150-1200The Trustees of the British Museum Gaja-Lakshmi ('Elephant Lakshmi') goddess of good fortune, about 1780 The Trustees of the British Museum

Gaja-Lakshmi ('Elephant Lakshmi') goddess of good fortune, about 1780 The Trustees of the British Museum Ardhanarishvara, lord who is half woman, Shiva and Parvati combined in one deityThe Trustees of the British Museum

Ardhanarishvara, lord who is half woman, Shiva and Parvati combined in one deityThe Trustees of the British Museum

Stunning still from the Songs of the BulbulAngela Grabowska

Stunning still from the Songs of the BulbulAngela Grabowska Stills from Songs of the BulbulAngela Grabowska

Stills from Songs of the BulbulAngela Grabowska

Anurag Bajpayee's Gradiant: The water company tackling a global crisis