“Success is when the boats have been stopped”. He has been short of political victories in the past six months, but prime minister Rishi Sunak was not content to hail the Safety of Rwanda bill finally getting through parliament without continuing to raise expectations about how much he will achieve with it. So the prime minister’s prize is to show if he can now make the Rwanda scheme finally happen – and that it would “stop the boats” if he does.

That plan could go wrong in two different ways. One is if the plans stall and no planes go to Rwanda, after all. The other, bigger headache arises if planes do go to Rwanda – and the theory of deterrence behind the policy is put to the test.

New polling for British Future finds only a quarter of the public would consider planes taking off for Rwanda as a successful outcome for the policy. Four in ten would need to see small boat arrivals reduced by half, as a result of the Rwanda scheme, before the policy could be considered a success.

The one certain consequence of the bill passing is that the UK government will now send president Paul Kagame of Rwanda his next instalment of £50 million. That increases to £290m the cash received by Rwanda, to be kept whether or not flights commence. Financially, that is a remarkable coup for Kagame – amounting to around three per cent of Rwanda’s GDP. Pro rata, this would be the equivalent of a £75 billion payment to the UK public finances. There will be further payments per person should anybody ever be sent to Rwanda.

Will any flights to Rwanda follow? Sunak was bullish about how much the government is doing to prepare, albeit while announcing a further delay: he now expects to take 10 to 12 weeks before the first flights to go to Rwanda. At the start of the year, seeking to head off a Commons rebellion, the government briefed

that a flight would be ready to go “within hours” of royal assent. Even a fortnight ago the government’s official message was that there would be flights this spring.

So the first rule of the Rwanda scheme is never to trust the government’s rather cloudy crystal ball or its media briefings. If the aim now is mid-July, that too might slip again.

Sunak is doubling down on the argument that the Rwanda policy will be transformative once it begins. “The only way to stop the boats is to eliminate the incentive to come by making it clear that if you are here illegally, you will not be able to stay,” he said on Monday (22).

It is an identical argument to the one Sunak made 13 months ago, in his March 7, 2023 speech, declaring that the illegal migration bill was the game-changing solution. He declared then that “if you come on a small boat today, the measures in this bill will apply to you,” – and that everybody who arrived from that day onwards would be removed within weeks.

The problem is that Sunak was bluffing - 52,000 people have come to the UK to claim asylum since he made that speech a year ago. Next to nobody has been removed or returned – outside of the UK government’s returns deal with Albania. The UK government had no real-world plan about where they could go.

The idea that the Rwanda scheme could fix this problem falls foul of basic mathematics. Rwanda will not be able to take even 500 people this year – so the scheme might or might not remove about one per cent of those already here. And using any of Rwanda’s capacity for those already in the UK would give the government no capacity at all to remove or deter the next arrivals.

Sunak promises a “regular rhythm of multiple flights every month over the summer and beyond until the boats stop”. Few others in government are anything like as optimistic about the number of flights.

But the Rwanda deterrent is another bluff – and one that is too easily called when the first flights go. Sunak’s vision is that sending the first flight will quickly deter crossings – and that continuing to send flights will see them reduce quickly to zero. It is a theory that collapses should more people arrive across the Channel this summer than are removed – something which the scale of the Rwanda policy makes all but inevitable. That would prove, within a week or two, that the policy is much less a deterrent than an expensive distraction from the government having no plan for 99 per cent of those it claims it can bar from the asylum system.

“Start the flights. Stop the boats. That’s what this bill delivers” is Sunak’s message. Testing the theory may simply prove it is a promise that he cannot deliver.

(The author is the director of British Future)

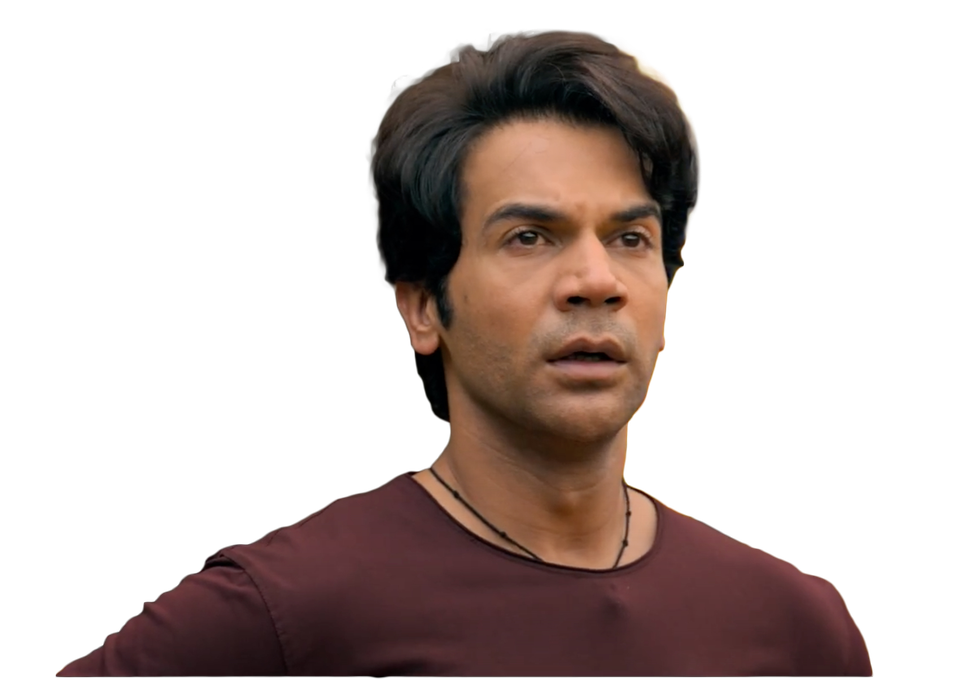

Bhool Chuk Maaf

Bhool Chuk Maaf If You Know You Know

If You Know You Know Asif Khan

Asif Khan Sanam figure out why. Teri Kasam

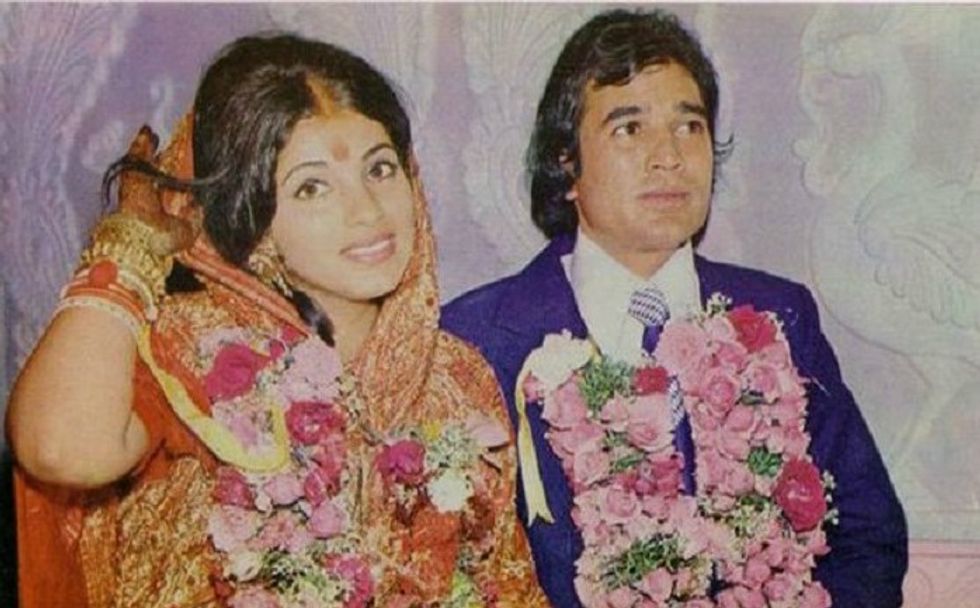

Sanam figure out why. Teri Kasam Dimple Kapadia and Rajesh Khanna on their wedding day

Dimple Kapadia and Rajesh Khanna on their wedding day Atif Aslam

Atif Aslam

Anoushka Shankar

Anoushka Shankar Nilesha Chauvet

Nilesha Chauvet

Pieter Elbers

Pieter Elbers