British voters rarely choose to change the government at a General Election, doing so only three times in the last half century: in 1979, 1997 and 2010. You need to be older than prime minister Rishi Sunak – born in 1980 – to have an adult memory of the last time a Labour government came to power.

That will change on Friday (5) morning. General election night 2024 will be at one the most and least predictable of modern times. There can never have been less doubt about which party will govern. Everything else about the result is unusually open.

“It’s not over until it’s over,” tweeted Sunak as he celebrated England’s great escape against Slovakia to survive in the Euro 2024 football championship. Jude Bellingham saved the Gareth Southgate era from fizzling out in the most disappointing fashion imaginable. Sunak has endured a still more frustrating election campaign.

But there is simply no political equivalent of a spectacular injury time equaliser when a party is 20 points behind in the polls. The Conservatives are no longer, realistically, competing with Labour to form a government: they are rather trying to avoid relegation by still coming second, by winning more votes than Nigel Farage, or stopping the Lib Dems becoming the official opposition in the House of Commons.

Sunak has a place in history as Britain’s first Asian prime minister. If he now combines that with leading his party to its worst ever general election defeat, how much of a shadow might it cast over that achievement?

Racism against the prime minister hit the headlines last week. Sunak reacted with passion to undercover footage of a canvasser for Reform in Clacton using the p-word against him. It is not language his daughters should ever have to hear. Their generation – as Sunak’s has – should benefit from our significant shift in social norms against racial prejudice. This episode shows how fair chances to reach the very top do not in themselves guarantee an equal experience of public life for Asian and black politicians, across parties.

Farage’s Reform Party responded to the racism against Sunak with sketchy conspiracy theories. Reform did finally suspend three overtly racist parliamentary candidates, once Farage could simply not defend the indefensible when read their quotes during the BBC Question Time special. The party has now suspended seven candidates for overt racism and BNP links since nominations closed. Farage has proved much more reluctant, however, to suspend racist candidates, in sharp contrast to the commendably firm line taken, albeit reactively, by his predecessor Richard Tice earlier this year.

So, Reform still retains parliamentary candidates who have blamed Jews for importing Muslims to the UK, declared themselves proud Islamophobes, and called for the deportation of Labour MP Diane Abbott – primarily, it seems because those specific quotes were not also read out to Farage on Question Time.

Even as he called out the racist abuse, Sunak spoke about the value of his ethnicity and faith having been “not that big a deal” for most people. Rationally, the evidence supports this claim. Sunak’s public reputation has soared and crashed over four short years in the public eye, yet his visible ethnicity has been constant throughout. No modern politician has ever hit the heights of public approval recorded for Sunak, as chancellor during Covid, after introducing the furlough scheme. Yet Sunak ends his premiership not far from hitting similar depths of public disapproval to Liz Truss.

Sunak was significantly more popular than his party on entering Downing Street. That gap has narrowed since. His political and policy choices have lost him the benefit of the doubt with the voters who initially preferred Sunak to the Conservative Party. That seems a clear proof that – for most people - it is much more the blue colour of Sunak’s party rosette, not the colour of his skin, that is at the heart of his electoral difficulties.

A new YouGov survey of ethnic minority voters finds Sunak has an unfavourable rating by 72 per cent to 21 per cent, matching his general public score exactly. Sunak had a 51 per cent to 29 per cent positive rating with ethnic minorities as chancellor – easily the best score ever recorded by a Conservative politician with minority voters.

He does also poll somewhat better with Indian voters – 36 per cent are favourable, though 57 per cent unfavourable – meaning British Indian voters on election eve prefer Keir Starmer to Sunak, giving a 53 per cent to 40 per cent approval rating to the Labour leader. Both leaders score negative ratings with Muslim voters of Pakistani and Bangladeshi origin.

Sunak’s final duty as prime minister will be to advise the King to call Starmer to form a government. Sunak will become Britain’s youngest former prime minister for two centuries, since Pitt the Younger left office in 1801. For Starmer, the challenge to deliver on his slogan of “change” will begin.

(The author is the director, British Future)

The actor with Kareena Kapoor, Sharmila Tagore and Saba Ali Khan

The actor with Kareena Kapoor, Sharmila Tagore and Saba Ali Khan Sharmila Tagore, Saba Ali Khan, Lord Jeffrey Archer, Soha Ali Khan, Saif Ali Khan and Kareena Kapoor at a 2013 event

Sharmila Tagore, Saba Ali Khan, Lord Jeffrey Archer, Soha Ali Khan, Saif Ali Khan and Kareena Kapoor at a 2013 event Saif's father, Nawab of Pataudi, Mansur Ali Khan

Saif's father, Nawab of Pataudi, Mansur Ali Khan

Farhan Khan

Farhan Khan Laapataa Ladies

Laapataa Ladies

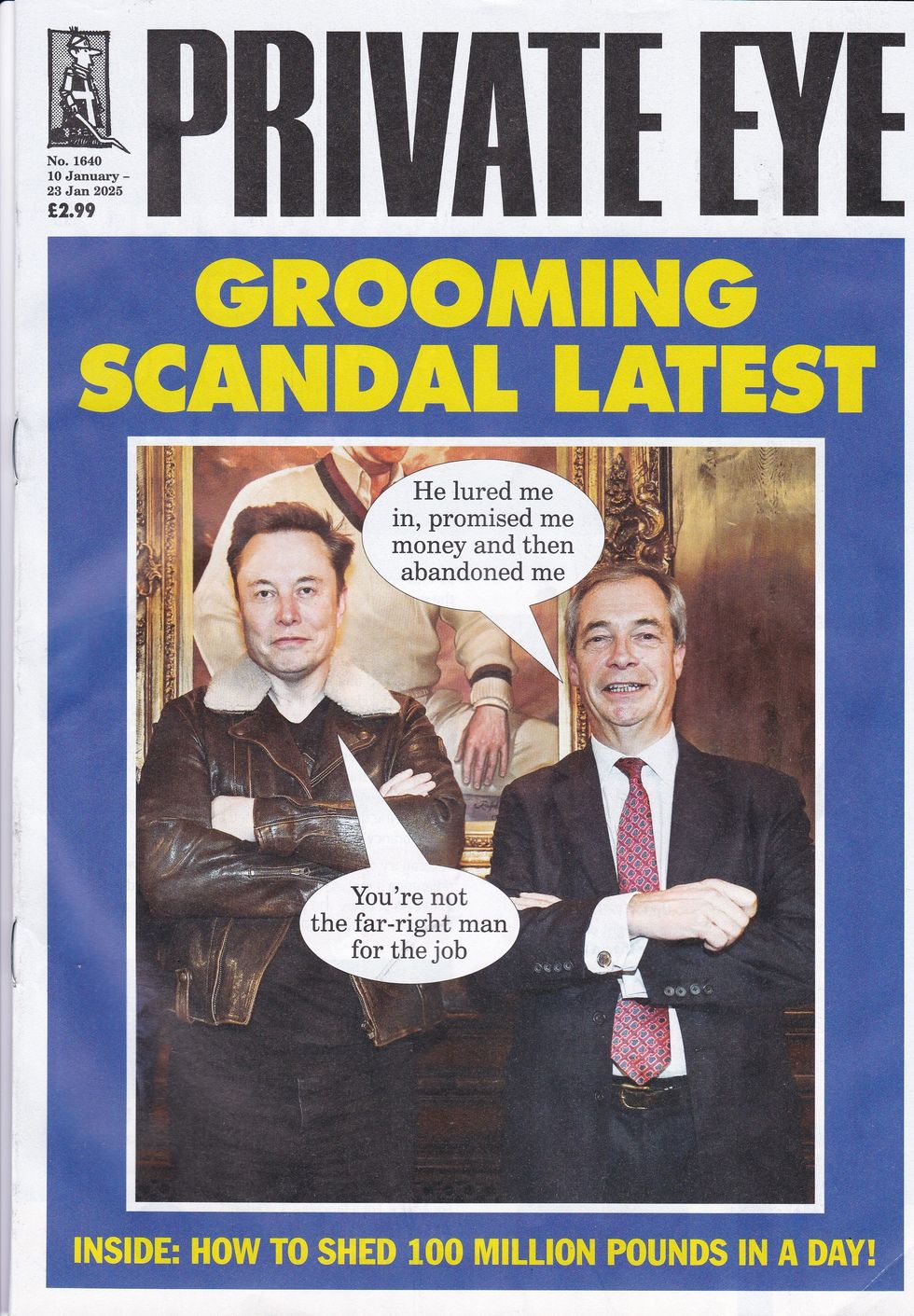

the Nigel Farage Private Eye cover

the Nigel Farage Private Eye cover Kemi Badenoch

Kemi Badenoch

Donald Trump

Getty Images

Donald Trump

Getty Images