WHEN the England women’s team won the 2022 European Championships, its head of medical Ritan Mehta felt joy and relief after years of near misses in major tournaments.

The final was the most-watched women’s football game on UK television, with a record 87,192 fans in attendance at Wembley Stadium.

“It was an incredible moment,” Mehta told Eastern Eye.

“We had to navigate lots of challenges with Covid, and injuries and illness.

“It was amazing to support the players to be able to achieve their dreams. It also had a wider societal impact which was a real privilege.”

Mehta has been the England women’s team’s head of medical/team doctor for more than a decade. He admitted he could never have imagined the explosion the game has experienced in that time.

The Women’s Super League (WSL) clubs generated £48 million in aggregate revenue in the 2022-2023 season, a rise of 50 per cent on the previous campaign.

The cumulative attendance surpassed one million for the first time across the WSL and the second-tier Championship in the 2023-2024 season, a knock-on effect after England finished runners-up at the 2023 World Cup.

As clubs capitalised on the surge in popularity by having women’s teams play in their main stadiums, matchday revenues among WSL clubs grew to £7m, while average attendance was up nearly 200 per cent on the previous season.

Arsenal’s women will play 11 of their home games at its 60,000-capacity Emirates Stadium next season, making it the primary venue for the team.

Mehta said, “I knew very little about women’s football when I first started. The clubs weren’t p r o f e s s i o n a l . They were still working semi pro – players were either working or studying alongside training.

“It’s been amazing to see the growth of the women’s game, but I think there it has much more room to grow.”

One area where Mehta believes the game can grow is to have more women and girls from ethnic minority backgrounds take up the sport.

During the 2021- 2022 season, the PFA estimated that only 10 per cent of players in the WSL were from black, Asian or ethnic minority backgrounds. While this figure appears to have increased slightly, a visual lack of any non-white players in some WSL line-ups this season has sparked a wider conversation about the need for diverse talent in the women’s top flight.

The number of British Asian professionals in the top division of women’s football stands at a paltry 0.3 per cent. That is despite south Asian women making up the largest single ethnic minority female group in the country.

“I think equality in this country is got a long way to go still. Football is a real big tool to try and improve that,” said Mehta.

“I have a young daughter and I think it’s inspiring for her to have these role models and see what they’ve achieved.”

Mehta balances his role with the FA with being the club doctor at Reading Football Club. He is one of many prominent British Asian doctors working at football clubs, along with Zafar Iqbal, head of medicine, Arsenal, and Imtiaz Ahmad, head of sports medicine and science at Crystal Palace.

“I live near Wembley, and I never imagined someone of my background or my community would ever step foot on Wembley Stadium or work at the FA,” said Mehta. “My dad used to take us (to Wembley) as kids, my brother and me, but there were very few Asians in the crowd. You felt conscious that maybe we don’t belong and there was this concern of racism.

“You never thought football stadiums could be a place where I’d belong. But when I started, I saw people like Zaf (Zafar Iqbal), Imtiaz (Ahmed), and Shabaaz (Mughal, former club doctor at Leyton Orient) in those environments. That made me think maybe it’s a place where I could belong too, and hopefully inspire others to feel they can belong as well, whether in football or other sports.”

Mehta added that there is a unique environment within women’s football, where people are working in unison for the development and growth of the game.

“No matter your background, there is a sense of community, there is a sense of belonging,” he said.

“Diversity is welcomed, because it helps to achieve the ambitions of the women’s game. I would tell people that ethnic diversity, or any diversity, is welcomed, respected and your skills will be utilised and given support to succeed.”

For Mehta, his long-term goal is to do research medicine and exercise science, specifically looking at female athletes. “There’s such little research out there. I actually did an article a few years ago about the lack of research in women’s sport, and particularly in women’s football, especially in comparison to what’s been done in the men’s game,” he said. “Females are different to males. We have to understand how an injury presents in a female is different to a male, and where do things like hormonal fluctuations come into play, and how does that affect the body, such as the joints.

“ T h e r e ’s still much to be done to better understand female athletes and how to support them. We can’t simply apply research done on men to women. It’s important to push the agenda for research in women’s football and sport in general.”

Mehta revealed sport was always his first passion, but felt that becoming an elite sportsman wasn’t possible for him, so he looked at a way to combine his love of sport and science.

He qualified in 2003 from Kings College London and initially trained and worked in general practice. He completed a masters in sport and exercise medicine and went on to complete a four-year specialist training programme in sport and exercise medicine.

Mehta said his career has been an “incredible journey,” including working at football World Cups, European Championships, and the London 2012 and Tokyo 2020 Olympics.

He is keen to inspire the next generation of British Asians to consider careers in a sports medicine.

“It’s really important to paint a picture where sport is a place where people of ethnic minority backgrounds can thrive and succeed,” he said.

“I’ve been able to work with a senior men’s team and women’s England football team, worked in multiple Olympic Games – these are experiences that I guess money can’t buy.

“In the Asian community, we’ve been so academic focused, especially with our parents’ generations. I was pleased that my parents were supportive of my different endeavour, of not just going down the traditional route and being able to do something a bit different and that’s opened so many doors for me and my family.”

Mehta isn’t the only son his parents supported towards an unfamiliar career choice. His brother Nikesh is the UK’s ambassador to Singapore.

Asked if there is competition between the brothers in their high-flying careers, Mehta said: “Where sport comes in, we always used to play sport together, so yeah, but not in our careers, because we work in such different careers.

“We’re very close. Our families are very close. We’re actually going to go and see him and the family in Singapore soon.”

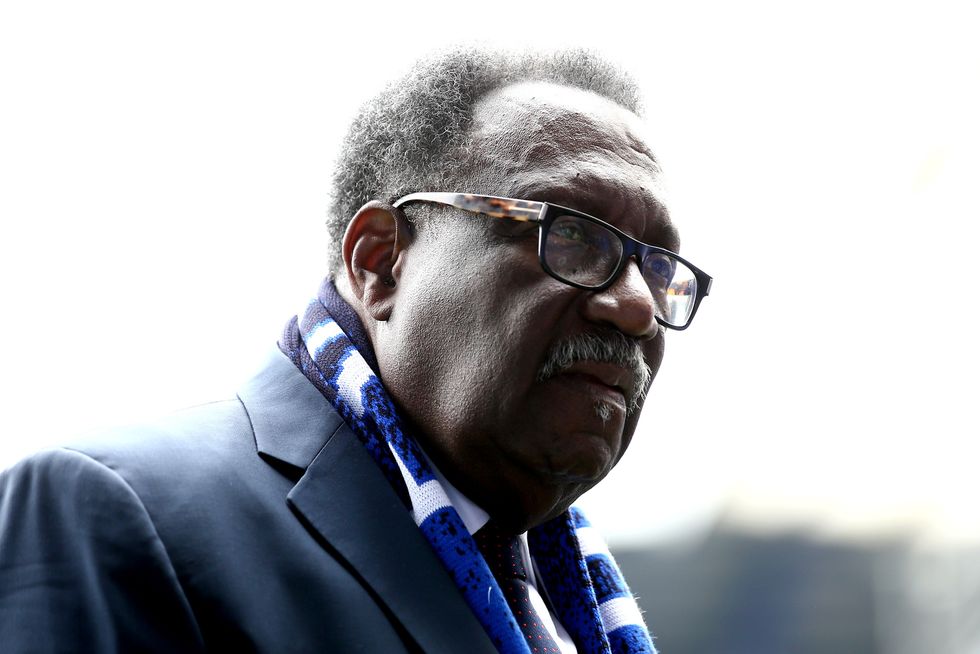

Clive Lloyd

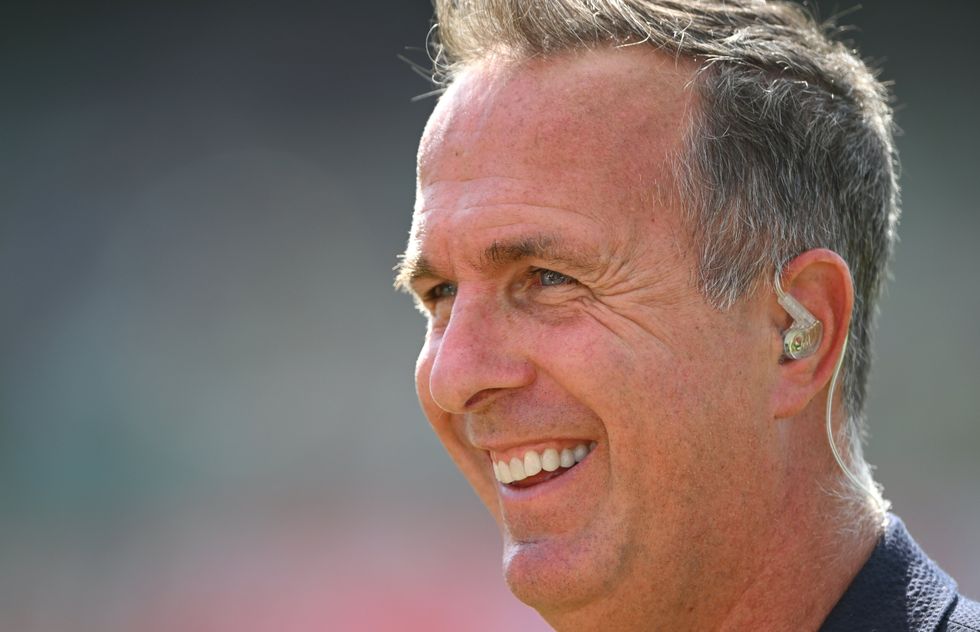

Clive Lloyd Michael Vaughan

Michael Vaughan