By Amit Roy

JONATHAN GLANCEY now lives in north Suffolk by the River Waveney, sometimes getting up at 6am to dig a trench to plant hedges.

The setting could not be more English, but Glancey is just the right man to compare and contrast the railways in America and in India.

A specialist publisher called Sheldrake Press has just brought out a lavishly illustrated book, Logomotive: Railroad Graphics and the American Dream, co-authored by designer Ian Logan and Glancey, who used to write about design and architecture for the Independent and Guardian dailies.

Glancey says it is possible to tell a great deal about a country from its architecture. The same, he adds, is true of railways, especially in the US and in India.

Logomotive is full of evocative pictures, many of them taken over several decades by Logan himself.

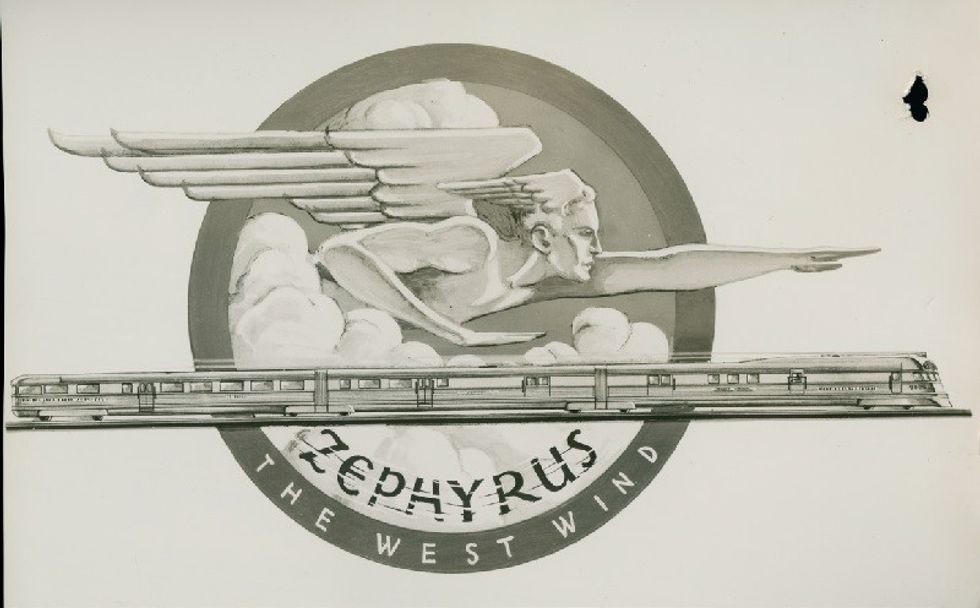

There is, for example, a Union Pacific X-18 gas turbine electric locomotive in Armour yellow and vermilion livery; the logo of the Burlington Zephyrus, the West Wind; the Southern Belle’s viewing car on the Kansas City Southern; the vast art deco waiting room of the Los Angeles Union Station; and passengers gathering beneath the zodiac vaults of New York’s Grand Central Terminal.

There is an illustration of the Orange Bloom Special going through the orange groves in Florida – “there is nothing like it anywhere in the world”.

There is also John Gast’s 1872 painting, American Progress, with three classic locomotives following the wagon trains of white settlers, “bringing with them the infrastructure of the Industrial Revolution”.

In a foreword, the architect Norman Foster admits: “In the 1940s as a pre-teenager, I would stand for hours at the end of the cul-de-sac next to my home in a Manchester suburb waiting for a glimpse of an express locomotive.”

He adds: “The ultimate marriage of machinery, branding, graphics, colour and lifestyle found its apex in American railroad systems.”

Glancey writes: “Even today the US railroad network is the world’s largest in terms of operating length. What has gone for the most part, and notably in the great land mass between east and west coasts, is the passenger train, its role usurped from the mid-1950s by the automobile and airplane, both supported by government subsidised interstate freeways and airports. This, though, was American progress. Mile-long run freight trains, meanwhile, continue to thunder on by, and profitably so, from the Atlantic to the Pacific coasts.”

Glancey tells Eastern Eye these trains can take several minutes to pass a given point: “If you stand by a railroad crossing in El Paso in Texas or something like that, and the bells ring and you hear the horns of the trains coming, the trains can be a mile long. And they can be longer than that – five huge, modern diesels [engines] on the front, pulling the train.”

The romance of American trains is captured in many films, among them High Noon and North by North-West. “Clint Eastwood loves them – here comes the train and the sheriff,” says Glancey.

That compares with such Indian films as the 1972 Hindi classic, Pakeezah, which has a famous train scene; and Train to Pakistan in 1988, based on Khushwant Singh’s partition novel.

Today, there are very few passenger trains crossing America. And the journeys can take between three and seven days, compared with a few hours by plane.

When it comes to passenger miles, China and India are far ahead, Glancey says. When he was 21, he went to India, travelled around the country by train and worked for a year in and around Calcutta (now Kolkata), where his father, Clifford George Alexander Glancey, who came from an Indian army family, was born.

The other day, the author Sathnam Sanghera, taking a dig no doubt at Michael Portillo’s TV travel documentaries, made fun of “white men getting off trains in India”. The Indian MP Shashi Tharoor has also argued the British built the railways in India so that they could get their loot out of the country.

But Glancey is grateful that he was encouraged to write about Indian railways by his editor at the Independent on Sunday, Ian Jack, who knows the country as well as any journalist in Britain.

Glancey points out that his father “spent most of his childhood in India, which was quite rare. In those days, the British tended to send their children back to England to be educated.

“But my very old grandfather – and my father had some of this in him – loved India the way it was. They just loved the place, the landscape, the culture.

“He came to England eventually when he was about 21. Then he became involved in helping to do geographical surveys of India. And during the Second World War, he signed up to the RAF.

“So then, life changed. He was assigned to Burma and was very much involved in the world of the ‘Forgotten army’ in that fight against the Japanese in north Burma and into the Naga Hills.”

Glancey went to India knowing something of its history. “Being English I had a romance slightly, a Raj romance. It’s generational and inevitable.

“And then you start to learn about India as you travel by train. English was a common language that could get me through any part of India.”

Glancey, who was fascinated by steam trains, travelled to Dimapur junction in Nagaland. In 2011, he wrote a book, Nagaland: A Journey to India’s Forgotten Frontier. On a trip in 1992, he rode the footplate of an Indian Railways WP-class Pacific steam locomotive from Delhi to Chandigarh. He also sat in the driver’s seat.

He assures Eastern Eye: “The drivers are big characters.”

These journeys are apparently musts for English steam enthusiasts. The BBC broadcaster Mark Tully had once said that “if I don’t get covered in soot, I would want my money back”.

Comparing India and the US, Glancey gives his considered opinion: “I think it’s the differences rather than the similarities between the railway systems of India and the US that stand out.”

Logomotive: Railroad Graphics and the American Dream, by Ian Logan and Jonathan Glancey with a foreword by Norman Foster, is published by Sheldrake Press. Illustrated hardback, £35.

Sudha Murty and her husband Narayana Murthy with their daughter Akshata, son Rohan and her sister Dr Sunanda Kulkarni

Sudha Murty and her husband Narayana Murthy with their daughter Akshata, son Rohan and her sister Dr Sunanda Kulkarni Rishi Sunak’s parents Usha and Yashvir Sunak

Rishi Sunak’s parents Usha and Yashvir Sunak

A street vendor looks at his smartphone on April 27, 2024 in Bengaluru, India. (Photo by Valeria Mongelli/Getty Images)

A street vendor looks at his smartphone on April 27, 2024 in Bengaluru, India. (Photo by Valeria Mongelli/Getty Images)