THE power of sport is its compelling, unscripted drama.

But triumph can rarely have turned to disaster so quickly as when Pakistan turned a 556-run total into an innings defeat to England.

England’s football fans may want to join India and Pakistan to make cricket our national sport too. As records tumbled in Multan last week, Greece beat England 2-1 at Wembley. They could have scored more.

In emotional celebrations after the final whistle, the team dedicated this first ever win over England to teammate George Baldock, who had died aged just 31. The good-natured Greek fans were as likely to take the Tube back home across London as to head to the airport.

The defeat seems to have ended England’s caretaker manager Lee Carsley’s appetite to replace Gareth Southgate permanently. He prefers to return to managing the under-21 team, a crucial talent pipeline for the England team beyond the crucible of media pressure.

Before the match, the Football Association (FA) was thinking ahead, not just to a new England manager, but in unveiling its strategy for 2024 to 2028. The past four years saw much progress, despite a pandemic. England men’s team reached two European finals in a row. The Lionesses won the European trophy and reached a women’s World Cup final.

Lord Herman OuseleyHigher hopes feel tantalisingly within reach. Both teams have a new Cup Final habit. I believe England’s men must be fated to win the 2026 World Cup. Sixty years on from 1966, three decades after starting to sing “30 years of hurt” and “football’s coming home” while hosting Euro 96, with a young team coming into their prime, a victory in North America feels almost too neatly scripted to come true.

The FA’s four-year strategy culminates with the UK nations and Ireland co-hosting Euro 2028 – an occasion with enormous reach and potential. ‘Inspiring positive change through football’ is the golden thread that the FA sees linking the power of major tournaments to inspire and connect with its broader vision for social change.

‘A game free from discrimination’ is another game-changing FA ambition by 2028. Lord Herman Ouseley was also warmly remembered in tributes at Wembley. The peer – cofounder of the Kick It Out anti-racism campaign three decades ago – died in early October.

For all the progress, new Kick It Out chief executive Samuel Okafor says “stubborn challenges” remain, emphasising accountability and data transparency to track progress on Asian players, black and female coaches and a football workforce that reflects our society. Reporting unacceptable behaviour – at the grassroots, in stadiums and online – matters to feel safe.

Yet the core point of kicking racism out was to pursue a shared goal – a national game where we can all feel that we belong.

The growing status of the women’s game helps that, though equal opportunities and status remain a long way off. ‘The Three Hijabis’ – Amna Abdullatif, Shaista Aziz and Huda Jawad – who have championed sport’s power for social change, pointed out at the Wembley launch contrasting strengths and weaknesses of the men’s and women’s game. Women’s football champions an inclusive culture – but with more to do to realise that vision across ethnic and faith groups.

Sunder KatwalaThe parliament will legislate on football regulation. Minimum standards matter – to protect clubs from misgovernance, and places from losing clubs that mean so much locally.

Positive cultural change needs other catalysts too. A core theme of Huddersfield Town’s third annual Inclusion and Empowerment conference earlier this month was how to move beyond compliance to become pacesetters for change. I heard Charlton Athletic’s ambitious vision, to be top of the league for community connection, when watching their impressive league win over Birmingham at the Valley recently.

The year 2028 will offer an opportunity to reflect on the scale of the black legacy in English football, half a century after Viv Anderson became the first of over 100 black full England international players. A focus on thousands more ethnically diverse qualified coaches will seek to narrow the stark gulf between the black presence on and off the pitch.

The British Asian presence in football remains much more nascent. Asian fans of my generation did feel benefits from the visible black presence. A multi-ethnic England team did broaden what it meant to be English – even without south Asian players in the team yet. The culture in stadiums, for club and country, did become less hostile, then more welcoming, over time.

The FA will now need to set stretching and achievable benchmarks to ensure these four years do see the emerging British Asian contribution break new ground at all levels.

Sports lovers know that winning every game can never be possible. But an increasingly diverse society should place a high value on setting – and achieving – meaningful shared goals.

(The author is the director of British Future)

A resident in Odessa, Ukraine, as smoke rises from a fire following a strike earlier this month amid the Russian invasion

A resident in Odessa, Ukraine, as smoke rises from a fire following a strike earlier this month amid the Russian invasion

Shweta Warrier

Shweta Warrier Harbans Singh Jandu

Harbans Singh Jandu Aamir Khan

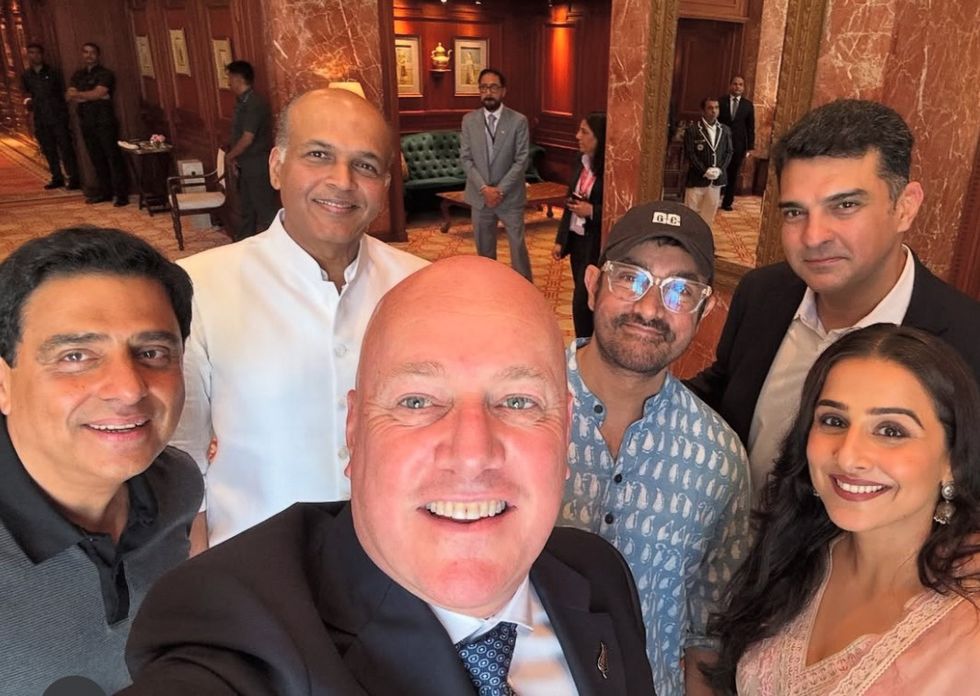

Aamir Khan Ronnie Screwvala, Ashutosh Gowariker, Christopher Luxon, Aamir Khan, Siddharth Roy Kapur and Vidya Balan

Ronnie Screwvala, Ashutosh Gowariker, Christopher Luxon, Aamir Khan, Siddharth Roy Kapur and Vidya Balan Madhuri Dixit

Madhuri Dixit

Manjeet Singh Riyat

Manjeet Singh Riyat