BENEGAL is considered the father of parallel, or new wave cinema in India. So central is his work to the movement that it forged an aesthetic of alternate or realistic Hindi cinema that reflected his socially conscious, yet deeply humanist mind.

In the 1970s, Benegal’s films revealed a world previously unseen, bringing stories of rural Indian reality to the forefront and heightening our awareness of class, caste, and gender politics – the winds of change sweeping across the nation. Here were characters in micro stories, but who represented much larger worlds where old feudal structures were collapsing and new, liberal ideals were growing.

Benegal made his first film Ankur (1974), based on the history of the Telangana movement (in south India) and the peasant revolt, in which a landlord’s son has an affair with a maid.

He shot on location in (then undivided) Andhra Pradesh state, cast Shabana Azmi – a fresh graduate from the Poona Film Institute – to play the central role of Lakshmi. There was a fresh pool of trained actors and technicians who became part of Benegal’s repertory. Naseeruddin Shah said the director cast him in Nishant (1975) at a time when the actor was being rejected by everyone else.

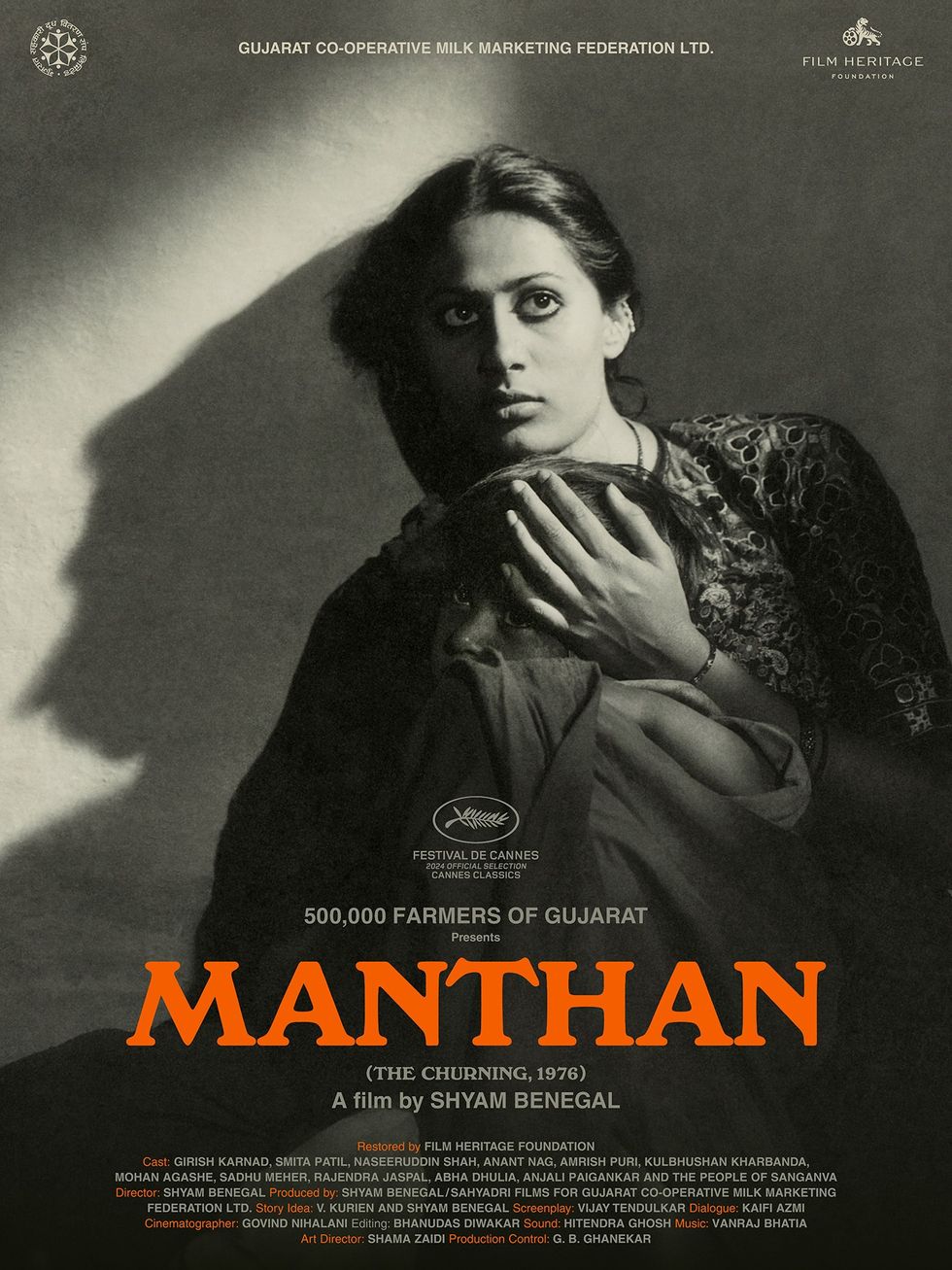

Girish Karnad, freshly returned from Oxford, stayed in Benegal’s home to write his scripts. He was cast as the urban doctor who tries to bring change and reform in the village in Manthan (1976). And we all recall Smita Patil’s smouldering performance in that film as the village girl who wants change, but is held back by patriarchal structures.

Benegal was on a roll and there were a host of actors – Amrish Puri, Om Puri, Anant Nag, Pankaj Kapoor and Neena Gupta – who were cast in these films.

While Benegal’s best films remain outstanding cinematic achievements, almost all his work is a vast cultural document – an insider’s view of the contemporary nation, its history, its heroes and underdogs, its women and outcasts.

For me, Benegal’s finest film is Bhumika (1977), based on the autobiography of the Marathi actress, Hansa Wadkar. Those were early days of the women’s movement in India and there was a vigorous cultural search for women’s writing and validation of women’s voices. Bhumika, with the excellent Patil as protagonist, takes us through the early days of theatre and cinema in (then) Bombay and the complex, emotional turmoil in her personal journey.

While Benegal’s biopics are very linear in structure – in Bose: The Forgotten Hero (2003) and Mujib (2023), the director often experimented with storytelling types in his features. The delightful Suraj ka Satwan Ghoda (1992) employs the Rashomon technique to question the basis of truth and perspective.

By this time, I was teaching at St Xavier’s College, Bombay, and Shyam babu (as we fondly called him) would readily agree to visit as a guest lecturer for my film studies students.

We would also often meet at the Film Society screenings and talks.

At one such event, I did a presentation on Suraj Ka Satwan Ghoda and sat with Shyam babu for a discussion on the film. Editor Anil Dharker liked the paper and published it in the Sunday Times the following week. I wrote long essays on Benegal’s films for Cinema in India, which Khalid Mohamed edited for the National Film Development Corporation (NFDC).

Soon after, I was on a post-doctoral project at the University of Sussex. I was curating for the India 50 Conference and programmed Bhumika for the screening.

We invited Shyam babu to be a keynote speaker and his presentation was one of the highlights of the conference. He stayed on in our London home for a few days and we binged on films and Chinese food in the heart of Soho.

When the British Film Institute (BFI) commissioned two books on Indian directors as part of the world directors series, I was asked to write the book on Benegal. With his extensive filmography, I travelled to Bombay and Pune to watch all the films, which included the fabulous documentary on Satyajit Ray. Shyam babu’s own archives are impeccably kept, and I found most of his films there.

Over cups of tea, we talked films in his office for three weeks. He said to me, “I don’t know if cinema can actually bring about change in society. But cinema can certainly be a vehicle for creating social awareness. I believe in egalitarianism and every person’s awareness of human rights. Through my films I can say, ‘Here is the world and here are the possibilities we have.’ It is difficult to define the purpose of my art… Eventually, it is to offer an insight into life, into experience, into a certain kind of emotive or cerebral area”.

The BFI book was launched in London by Karnad, an old friend and colleague of Shyam babu, who was then minister of culture at the Nehru Centre. The British Council organised a series of launch events in India – in Delhi, Bombay and [then] Calcutta.

In the past two decades, every trip to (now) Mumbai involved a meeting with Shyam babu in his Tardeo office. Over 50 years, his daily routine meant being at the office from 9am to 5pm, with a short lunch break at home. Even after he turned 90, he would be in his office regularly meeting people, taking calls, planning projects.

I travelled with the unit on several of his films. In Jaipur, Rajasthan, for Zubeidaa (2000), the shoot was at the Deegi Palace Hotel. A long table was laid out in the lawn and all the cast and crew assembled there for meals. This was a love story, but Shyam babu placed it in a historical context and gave it credibility.

During the filming for Bose: The Forgotten Hero, we were in Berlin working with a large number of German actors, including one who played Adolf Hitler in the film. During the pandemic, I saw him helming a 200-crew unit in Film City, filming the pivotal scenes of Mujib, an Indo-Bangladesh co-production. At 88, he paced up and down in the sun with a cap on his head, making sure things were on schedule, even as the sun went down in the western sky. Once the shoot was complete, his assistants gathered around him as they read the scenes for the next day.

It was amazing to see the strict disciplinarian at work, yet how kind and compassionate he was with every person he interacted with.

Earlier this year I was in his office, sipping chai and watching Mujib, his last film, a biopic on the Bangladesh liberation leader. He was happy talking to us, sharing stories, and excited about the film screening in London.

After a great deal of persuasion, we were able to send him home for lunch and rest. But, he was back within an hour, fussing about whether we had lunch, what we would like.

I am so glad that last summer we were able to do a digital tribute event for Shyam babu’s 50 years in cinema, partnered by BaithakUK and the London Indian Film Festival. We had director Adoor Gopalakrishnan, Bina Paul, Naseeruddin Shah, Shabana Azmi, Nandita Das, Nandita Puri, Ila Arun, his long-term writers Shama Zaidi, Atul Tiwari, composer Shantanu Moiitra and the Mujib star Arifin Shuvoo from Bangladesh.

With his typical humility, he said he wasn’t sure whether he deserved this honour, but then warmed up as each speaker came on screen and was finally excited as a child, declaring, “this calls for a party!”

His last words for the book were, “I’d like to go on making films. I don’t think I can do anything as well, I’m not even sure I do this well enough… India continues to inspire with a variety of different subjects to work on.

“I love doing films on the temperature of society and capture the transition of this amazingly diverse structure of our nation. But I need to be driven by the subject, to be completely possessed by it.”

We will miss Shyam babu, a giant filmmaker and an amazingly compassionate man. A teacher for life, someone who the late Om Puri constantly referred to as his “encyclopaedia” and many of his illustrious cast consider as a mentor.

But, we will celebrate the amazing storyteller, the prolific maker of 25 feature films, 40 documentaries, six television series including the legendary Bharat Ek Khoj and Samvidhan (The Constitution), the man of incisive historical sense and of deep empathy.

The best tribute is to celebrate his work and make the films accessible to the younger generation. In 2024 the Film Heritage Foundation has restored Manthan, and a mint copy has circulated in major film festivals, starting with Cannes in May 2023.

While watching the film at the Festival of 3 Continents in Nantes, France, a few weeks ago, I was elated to see a large number of young French film students in the hall. During the 50 years tribute to Shabana Azmi, several of Bengal films were shown. As we watched Mandi, with every scene the best screen talent appeared – Shabana Azmi, Naseeruddin Shah, Om Puri, Smita Patil, Neena Gupta, Pankaj Kapoor, Annu Kapoor, some in tiny cameos just because they wanted to be in a Benegal film.

What a revolution Shyam Benegal had ushered in Indian cinema. Hurrah to that.

With actor Kanwar Dhillon in 'Ram Bhavan'Instagram/ rahultewary

With actor Kanwar Dhillon in 'Ram Bhavan'Instagram/ rahultewary Udne Ki AashaScreen Grab 'Udne Ki Aasha'

Udne Ki AashaScreen Grab 'Udne Ki Aasha'

Mrunal Thakur in Sita Ramam

Mrunal Thakur in Sita Ramam  Director Anjali Menon

Director Anjali Menon Actress Nayanthara

Actress Nayanthara

Seated Jain enlightened teacher meditating, about 1150-1200The Trustees of the British Museum

Seated Jain enlightened teacher meditating, about 1150-1200The Trustees of the British Museum Gaja-Lakshmi ('Elephant Lakshmi') goddess of good fortune, about 1780 The Trustees of the British Museum

Gaja-Lakshmi ('Elephant Lakshmi') goddess of good fortune, about 1780 The Trustees of the British Museum Ardhanarishvara, lord who is half woman, Shiva and Parvati combined in one deityThe Trustees of the British Museum

Ardhanarishvara, lord who is half woman, Shiva and Parvati combined in one deityThe Trustees of the British Museum

Mahesh Kale at his concert 'Abhangwari'Instagram/ maheshmkale

Mahesh Kale at his concert 'Abhangwari'Instagram/ maheshmkale