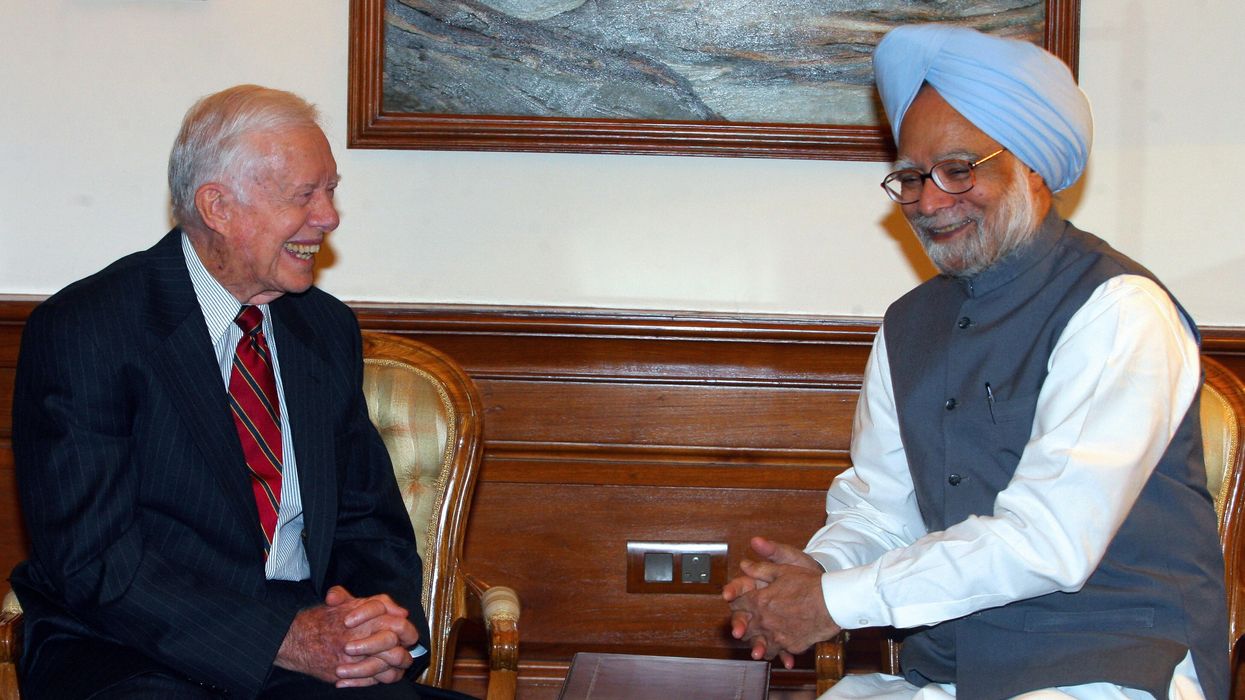

THE world lost two remarkable leaders last month – the 13th prime minister of India, Dr Manmohan Singh, (September 26, 1932-December 26, 2024).and the 39th president of the US, Jimmy Carter (October 1, 1924-December 29, 2024).

We are all mourning their loss in our hearts and minds. Certainly, those of us who still see the world through John Lennon’s rose-coloured glasses will know this marks the end of an era in global politics. Imagine all the people; /Livin’ life in peace; /You may say I’m a dreamer; / But I’m not the only one; /I hope someday you’ll join us;/ And the world will be as one (Imagine, John Lennon, 1971) Both Singh and Carter were authentic leaders and great humanists. While Carter was left of Singh in policy, they were both liberals – Singh was a centrist technocrat with policies that uplifted the poor. They were good and decent human beings, because they upheld a view of human nature that is essentially good, civil, and always thinking of others even in the middle of bitter political rivalries, qualities we need in leaders today as our world seems increasingly fractious, self-absorbed and devolving. Experts claim authentic leadership is driven by:

1. Purpose: Authentic leaders rely on purpose and vision to achieve longterm goals.

2. Discipline: Strong work ethic for management and the team.

3. Empathy: Heart and compassion.

4. Transparency: Incorruptibility. To be clear, Carter and Singh were no martyrs or saints, but they had sagacity and vision. They seemed high on human personality traits, such as:

■ Introspection (a high score means you are self-aware, reflective, and emotionally engaged);

■ Agreeableness (a high score means you are kind, sympathetic, affectionate, and you are likely to engage in prosocial behavior and volunteerism; and

■ Conscientiousness (a high score means you are hardworking, ambitious, energetic, persevering, and like to plan things in advance).

These traits made them effective and empathic leaders, maybe not the best of the communicators to their public.

Their humble origins accounted for their humility in public service. Singh rose from the Punjabi plains – the wheat capital of India – before the Partition that created India and Pakistan. He witnessed the scourge of political violence and poverty at the end of colonialism, when, at the age of 15, his family relocated from what is now Pakistan and settled in Amritsar, Punjab.

Singh lost his mother at a young age, which (I have written elsewhere) is a key driver of innovative leadership. Similar to (former US president) Barack Obama, his daadi (paternal grandmother) raised him. Like (US ex-president) Abraham Lincoln, he studied under candlelight during his school days, as his village had not yet been electrified. Singh married Gursharan Kaur in 1958 and they have three daughters – Upinder (a historian at Ashoka University), Daman (an independent author) and Amrit (a civil rights attorney at ACLU [American Civil Liberties Union]).

Carter was a son of a peanut farmer from the plains of Georgia, who grew up during the Great Depression and under the brutal Jim Crow laws that continued to divide American society well after the Emancipation Declaration.

He was the first American president born in a proper hospital. He grew up with poor African-American children who were part of hired help on the farmland, and his mother was often absent, because she worked long hours.

Scarcity and suffering are great character builders – adversity turned Carter into a man of faith, and Singh into a man of economics. Both were brilliant students as young men, and joined government service as young adults, which shaped their global identity.

As finance minister and later as prime minister, Singh became a transformative technocrat who changed India-US relations by structuring two major paradigm shifts – India’s economic liberalisation in 1991 and the India-US civil nuclear agreement in 2005.

He was part of the ‘silent generation’ shaped by his education at Cambridge and Oxford. His policies may have moved a billion people out of poverty, and created the Indian middle class, the engine of economic growth of the third-largest economy in the world.

Singh told Mark Tully that two professors shaped his intellect (Joan Robinson and Nicholas Kaldor): “Robinson propounded the left-wing interpretation of [John Maynard] Keynes, maintaining that the state has to play more of a role if you really want to combine development with social equity.

Kaldor influenced me even more – I found him pragmatic, scintillating, stimulating. Joan Robinson was a great admirer of what was going on in China, but Kaldor used Keynesian analysis to demonstrate that capitalism could be made to work.”

In addition to his many political achievements, Singh was known for his humility and dearth of speech. I met him as a young graduate student at the Delhi School of Economics (1994), when he was the finance minister under prime minister PV Narasimha Rao, while I was researching Indian villages at the outskirts of Delhi . He wore his signature starched, white kurta with a light blue turban, and his greyish Sikh beard. I shook his hand and shared stories.

He previously served as a professor before heading the Reserve Bank of India. Singh is credited for jettisoning the Nehruvian legacy of Fabian socialism.

While Singh became prime minister during the Obama years, his authentic leadership style had much in common with president Carter. For their purposeful visions, strong values, and transparency, they may not have been the most brutal of politicians. Yet, their personalities grew larger in the rearview of history and acquired a humanistic persona.

President Carter was part of the greatest generation, sandwiched between the two world wars, that saved millions of lives. He contributed hugely to eliminating guinea worm disease in Africa, saved the first nuclear meltdown as a naval physicist off the coast of Canada, and amended the clean air act to ban CFCs that depletes the ozone layer. Banning CFC was a big deal at the time, but nobody may have even noticed. Just like his solar panels on the roof of the White House were immediately removed, because he was granted only one term. But Carter’s impact only grew in his post presidency as he went on to win the Nobel Peace Prize for his humanitarian work.

Carter is also known for Carterpuri, a village in Haryana his family visited (in 1978) and where his mother was a peacecorps volunteer in the 1960s (see related story, page 17). He was the third US president to visit India, after [Dwight D] Eisenhower and [Richard] Nixon, and continued the alignment between the two longstanding democracies:

In his address to India’s parliament in January 1978, he said, “For the remainder of this century and into the next, the democratic countries of the world will increasingly turn to each other for answers to our most pressing, common challenge – how our political and spiritual values can provide the basis for dealing with the social and economic strains to which they will unquestionably be subjected.”

One of my psychology professors used to say, ‘Americans will never elect a person like Mahatma Gandhi as a US president.’ Will Americans ever re-elect Jimmy Carter? Conversely, will Indians ever vote for a person like Singh again? Seems highly unlikely in the age of half-truths and misinformation.

Carter’s authentic leadership style seems to be from a bygone era – a Bible school teacher, peanut farmer, naval engineer and physicist, southern governor turned US president. Carter’s passing seems to mark the end of the American century, and his full century.

I never met president Carter, but I have an early memory of looking at his portrait at the US Consulate in New Delhi, through the thick looking glass, when as a young teenager I arrived for an immigration interview.

The year must have been 1976 or 1977, which marked America’s bicentennial celebrations, and the year that the Indian government instituted the Emergency. That’s the year that changed everything.

Dinesh Sharma is a director and chief research officer at Steam Works Studio, an edtech venture in Princeton, NJ, and a faculty member at Fordham University and NYU.

Anurag Bajpayee's Gradiant: The water company tackling a global crisis