A NATIONAL exhibition celebrating the role of migrants in the NHS opened in Leicester in June and will tour the country later in the year.

The Migration Museum’s Heart of the Nation aims to highlight the contribution of those who moved to the UK to work in the NHS, which celebrates its 75th anniversary this year.

“The NHS really wouldn’t have survived without migrants who came to work in all levels of the organisation, particularly in general practice and specialities that were less attractive to British trained medical professionals,” said exhibition curator Aditi Anand, who is also artistic director at the Migration Museum.

Founded in 1948, the NHS recruited migrants as consultants, doctors, nurses, midwives and dentists. Today, one in six people working in the health service has a non-British nationality, while many others are the children and grandchildren of migrant healthcare workers.

Anand told Eastern Eye, “Not only did migrants fill gaps in staff shortages, they also brought in a huge amount of innovation – in pioneering surgeries and medical treatments.”

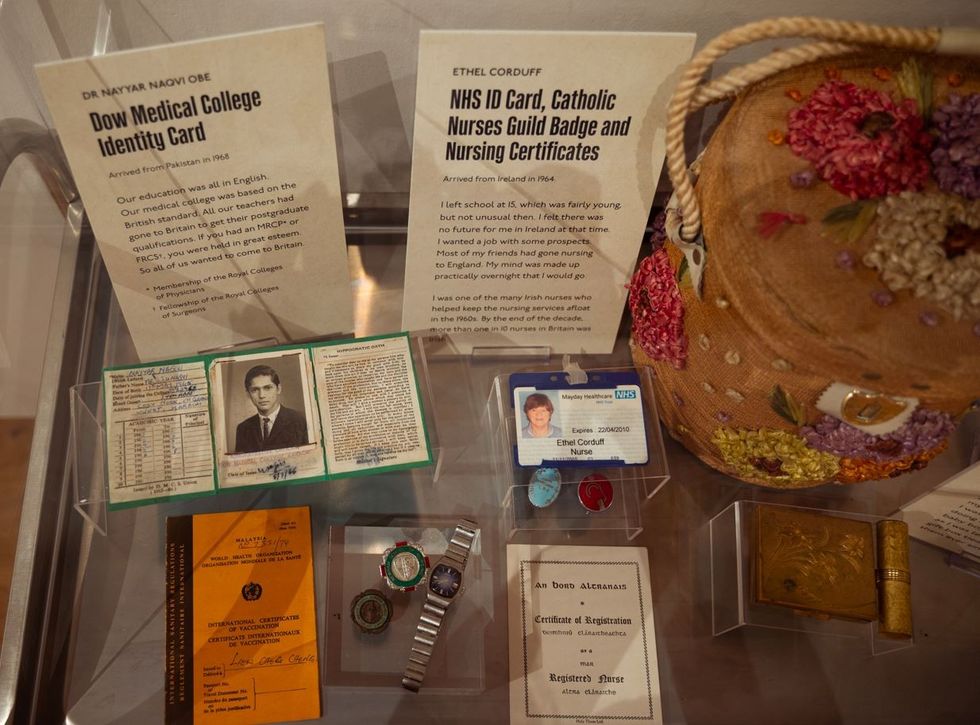

The exhibition features personal stories from healthcare workers – bought to life through photography, film, newly commissioned artwork and unique artefacts – from the 1940s to the present day.

“In many ways, migrants have been written out of the story of the founding of the NHS,” said Anand.

“When we go to hospital or see a GP, we see migration, it’s visible to us, but I don’t think it’s as obvious just how central it is, particularly in the early years, early decades, when there were huge staff shortages, because, essentially, this was a new system. At the time, many British trained doctors were emigrating to Canada, Australia and the United States, where they were getting paid a lot more money than if they stayed in the NHS.”

Heart of the Nation builds on a digital show the museum unveiled in 2020, when the sacrifices of migrant doctors became evident.

“When the pandemic hit, we decided it was a really important moment to acknowledge the NHS migrant story. The digital experience was responding to migrants in the NHS, but also looking at the fact that many of them were disproportionately affected by the pandemic. Some of the earliest doctors and nurses who died were from migrant backgrounds. It was obvious there was a disproportionate effect,” said Anand.

“Since then, we’ve continued to add stories and we’ve now launched it as a physical exhibition.”

The latter opened in Leicester in June. Its centrepiece is a newly commissioned interactive music and video installation, created and performed by seven NHS staff, exploring themes of care through song and storytelling.

“We worked on this piece for six months. The NHS workers, from migrant backgrounds, worked with a music director,” said Anand.

“It’s an immersive experience that takes place inside a big pod, six metres in diameter. Visitors can sit on these blood transfusion-type chairs which give the sense of being in a hospital setting.

“Then the film is projected all around you, 360 degrees, and you listen to people talking and singing about care and what it means to them.”

Anand said the idea came from a story by children’s author and poet Michael Rosen, who had Covid and was put in an induced coma in March 2020. At the time, the 77-year-old was given a 50:50 chance to live.

When he woke up, 40 days later, it was to the sound of singing. “When he was in the wards, not sure whether he was going to live, Rosen heard a Jamaican nurse singing No Woman, No Cry. When he tweeted this, suddenly, others started responding and saying, ‘something like that happened to me as well. My mother was essentially in her final hours and the nurse sang to her’; or ‘my daughter was about to go into chemotherapy and the nurse sang a song to her to comfort her’,” said Anand.

“It seemed like singing was a way for people to demonstrate care and healing. That’s sort of where the idea came from – to do something around music. For all of us, songs make us feel certain emotions that are difficult to put into words.”

Dr Adil Akram, a psychiatrist working in the NHS, is one of the singers and co-creators of the music and video installation. His father moved to the UK from Pakistan in the 1960s to practise as a doctor in the heath service.

Akram said, “This exhibition is close to my heart – it’s about the contribution of people like my father who came to this country and spent their lives and careers helping to build the NHS into the fantastic institution it is today, that symbolises all the good things about the UK.”

Visitors finish their tour at an interactive “healing space”, where they can share their stories and add messages for NHS workers who have cared for them.

Anand said, “For all its challenges, the NHS remains an immense source of national pride and is often painted as a distinctly British success story.

“Heart of the Nation highlights the vital role migrants played in the NHS and the extent to which – just like the NHS – migration is central to the very fabric of who we are in Britain, as individuals, communities and as a nation.

“Now more than ever, this is a story that needs to be told.”

- The Heart of the Nation exhibition opened at Leicester Museum & Art Gallery on June 30 and runs until October 29, the first leg of a national tour. Future confirmed locations include Leeds and London.