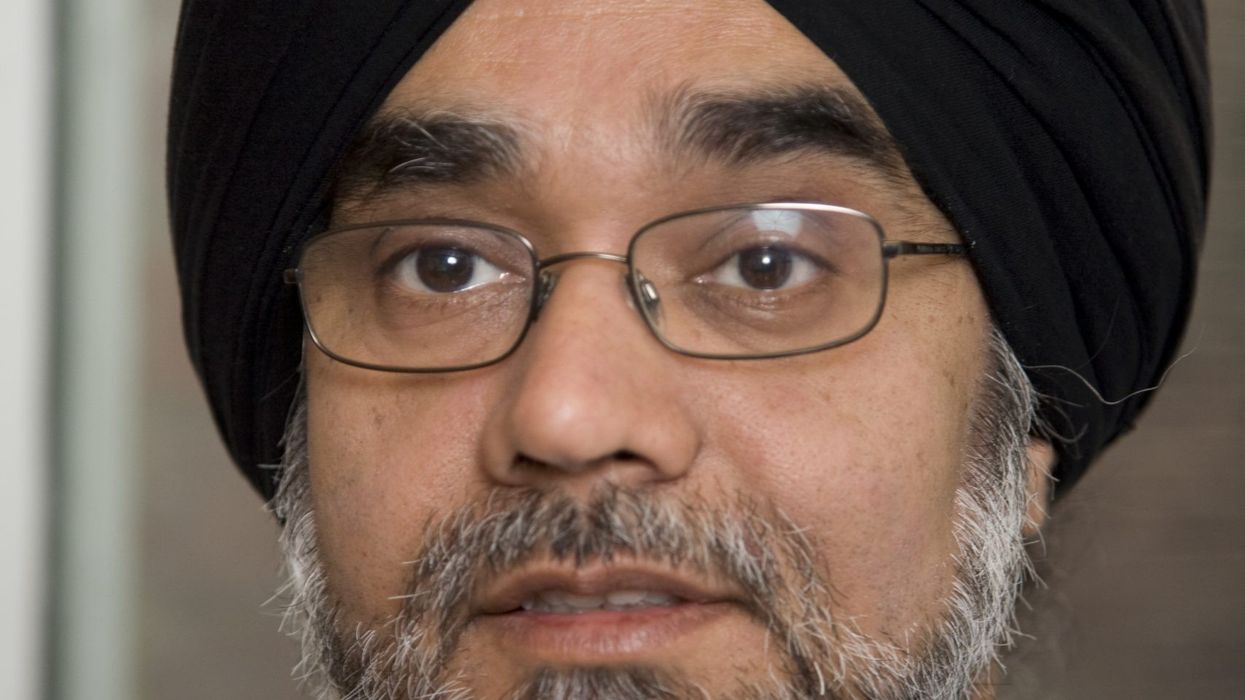

ONE OF the most significant rulings relating to immigration in the past 12 months had an Asian judge behind it.

In June 2022, Justice Rabinder Singh of the Court of Appeal in London ruled that the first flight to take migrants arriving illegally in Britain to Rwanda could go ahead, dismissing campaigners' attempts to win an injunction to stop it.

It was a win for the Conservative government for whom keeping migrant numbers down was a key manifesto pledge.

Early last year, then Home Secretary Priti Patel signed a controversial partnership deal with Rwanda to send some migrants to the African country for resettlement even as illegal migrants tried to make their way to the UK on small boast across the English Channel.

However, charities and a trade union launched an appeal against the government's plan to send asylum seekers to the East African nation after the High Court ruled the first planned flight could take place.

In his ruling in summer, Judge Singh said the Court of Appeal could not interfere with the High Court judge's “clear and detailed” judgement and refused permission for further appeal.

Singh has served as a Court of Appeal judge (since October 2017) and has been president of the Investigatory Powers Tribunal (since September 2018).

Other prominent cases in the past year included a ruling in April 2022 that the use by ministers of Whatsapp and personal email for official government purposes did not break the law.

Justice Singh and Justice Johnson said the existing law on keeping public records said "nothing" about the use of personal devices for government business.

While campaigners argued that the use of messaging services such as Whatsapp made it easier to delete information and cover up possible wrongdoing, the judges said the use of auto-delete software was not unlawful.

Singh is known for his insight and impeccable knowledge on complex legal matters, such as judicial review, equality and privacy, human rights as well as criminal and international law.

He has previously credited his success to Cambridge university, where he acquired a law degree from Trinity College, and also the University of California, Berkeley, from where he did his master of laws (LLM.).

“Cambridge offered a very good technical legal education, while the University of California complemented that. Americans always tend to think of law in its social and political context,” Singh said to LSE Law School’s Professor Conor Gearty, discussing his new book ‘The Unity of Law’ in 2022.

The son of immigrant Indian parents, Singh’s journey to the top echelons of the UK justice system is one of hard work, struggle and eventually, success.

He grew up in Bristol and in a 2011 interview said his interest in law was sparked by watching barristers on television.

Another source of motivation was the book, To Kill a Mocking Bird, by Harper Lee, set in a southern US state during the late 1930s. The story centres around Atticus Finch, a white lawyer who defends a black man accused of raping a white woman during the depression.

“Atticus Finch talks about the law as the great equaliser. It’s clear he is a lawyer who regards himself as having a vocation. He will do his duty, even if he knows he’s going to lose the case, because it’s the right and just thing to do,” Singh said.

He is also an avid reader of plays and literature, with a particular fondness for Greek and Latin classical works and authors who “can put themselves into the character of someone completely different.”

In an interview given to Counsel Magazine, Singh said literature enables judges “to understand the world from different people’s perspectives.”

From a young age, Singh had an interest in human rights. However, human rights were not really taught at UK universities when he was a student.

While at Cambridge, Singh heard about the work of professor Frank Newsman, the co-author of the first book on international human rights law for the English-speaking world.

Singh subsequently was awarded a Harkness Fellowship and taught by professor Newman, whom he described as a “very inspirational figure”.

Singh has said, “Human rights principles seep into everything. They are found in family law, criminal law, and they are even found in commercial law. If you cannot see it, you cannot be a good lawyer.”

When he returned to the UK from America, Singh was called to the Bar (Lincoln’s Inn) in 1989.

However, his finances did not permit him to take the bar exam, so Singh turned to academics and became a law lecturer at the University of Nottingham. Later, he won a scholarship and

took silk in 2002. He was elected a Bencher of Lincoln’s Inn in 2009 and Singh served as a deputy High Court judge from 2003 to 2011 and as a recorder of the Crown Court from 2004-11.

In October 2011, he was appointed a High Court judge (Queen’s Bench Division, now King’s).

Singh has touched upon “the values that underpin the common law of a society”.

The interesting facet of common law, Justice Singh said, is that it is sufficiently flexible as well as adaptable.

“The common law has been capable of embracing new and different values from time to time.

“There are values like the importance of liberty and equality. However, if you consider law as a system, the relationship between the law and values is very a complicated one,” he said to Professor Gearty.

In his long career, Singh has represented a variety of people and organisations, including those accused of terrorist offences, pressure groups such as Liberty, as well as the government itself.

In the 2004 Belmarsh case, Singh successfully representing the campaign organisation Liberty in the House of Lords against the indefinite detention without charge or trial of non-nationals suspected of terrorist activities.

Last year, the Court of Appeal in November upheld legislation which allowed the abortion of babies with Down's syndrome up until birth.

Heidi Crowter, 27, who has Down’s, took the Department of Health and Social Care to court in the hope of removing a section of the Abortion Act.

Judges had previously ruled in September 2021 that the legislation was not unlawful, but the case was reconsidered by the Court of Appeal at a hearing in July 2022.

Lord Justice Singh and Mrs Justice Lieven had said at the time that the legislation was a matter for MPs, rather than the courts.

Singh is clear about the role of judges. He has said “It is not the function of judiciary to impose values on societies. But we need to make sure that the common law is able to meet the needs and requirements of a democratic society.”

As a judge, Singh has said, “I have a loyalty to the law and I try to find what the right legal answer is.”

On the role of the Investigatory Powers Tribunal, Singh said, “We as a society entrust the so-called investigation agencies with abundant power. However, the public wants to know that the power is exercised properly and lawfully.

“So, a number of mechanisms have been introduced over the last 20 or more years. They include the creation of the Office of the Investigatory Powers Commissioner (IPCO) in 2016 among others. The idea is to ensure law in the first place protecting the interests of the nation.”

In 2021, he published a book titled ‘The Unity if Law’, which reflects on the defining themes of his legal career.