THE government has been urged to invest in stem cell donor research after a study revealed that Asian children were more than twice as likely to die as their white counterparts following a donor transplant.

Asian children face the highest risk of fatal complications among all ethnicities, with a 32 per cent chance of death within five years of a donor transplant, compared with just 15 per cent for white transplant patients.

The data comes from a report published last Wednesday (4) by stem cell charity Anthony Nolan and the British Society of Blood and Marrow Transplantation and Cellular Therapy.

Dr Neema Mayor, director of immunogenetics and research services at Anthony Nolan and lead author of the study, told Eastern Eye that addressing the reasons behind these health inequalities is now vital.

“I am of mixed Asian heritage. To me, this is a very sad and disappointing finding,” she said.

“However, it’s incredibly important that we’ve done this research. We now know the inequity exists, and we can finally start tackling it to improve the lives of all affected patients.”

A stem cell transplant involves replacing a patient’s unhealthy blood stem cells with new cells from either the patient or a genetically matched donor. It can treat conditions such as leukaemia, aplastic anaemia, and multiple myeloma

Ethnicity was found to have a significant impact on patients who received a transplant using donor cells, with no impact of ethnicity seen for patients who had a transplant using their own cells.

Adult patients from a black and Asian background had the worst survival rates after treatment and were 1.5 times more likely to die within five years of a donor transplant compared to white patients.

The research looked at more than 30,000 patients who had a stem cell transplant between 2009 and 2020 in the NHS, including 19,000 cancer patients.

It accounted for factors including age, disease type, transplant type and level of donor matching. Patients had previously identified whether their ethnicity was Asian, black, white or other (patients of more than one ethnicity or any other declared ethnicity).

“Despite stem cell transplants having been used as a treatment for blood cancer and blood disorders for more than 50 years, until now there was little known about the health inequalities experienced by patients in the UK,” said Mayor.

“While our analysis cannot explain why this difference occurs among ethnicities, we know there are likely complex genetic, socioeconomic, and systemic factors intersecting with ethnicity to affect outcomes.”

“Our research is investigating the impact of many of these factors, so we can continue to work to ensure all patients have equal access to, experience of and outcomes from a stem cell transplant.”

Mayor added that whilst there has so far been no official response from the NHS, transplant centres across NHS sites have been supportive of the study and shown a willingness to support the research going forward looking at the reasons for the inequalities.

Caitlin Farrow, director of strategy and influencing at Anthony Nolan said: “A stem cell transplant is a last-chance treatment for thousands of patients each year with blood cancer or a blood disorder, and it’s shocking to see the stark disparity in outcomes for patients from black, Asian and other minority ethnic groups.

“Understanding the scale of the issue is the first step to drive change. Now, it’s essential that charities, healthcare providers and government alike act on these findings by investing in research to unpick and address the causes of disparities in stem cell transplants.”

The results reinforce research in other countries like the US which indicate patients from minority ethnic backgrounds have worse outcomes from stem cell transplants using donor cells.

Mayor revealed her team is currently working on multiple projects that are looking at the different stages of the transplant process and trying to determine whether inequity existed at these different stages and if it does exist, coming up with strategies to address it.

“It’s also important to say that although there is a difference in outcomes for patients from Asian and black backgrounds, it’s still an incredibly important treatment option for them,” she said.

“For any patient who needs to have a stem cell transplant, their option otherwise might not be very good. It’s often a last chance treatment for patients with blood cancers. This is still a very, very important treatment option.”

Previous research has shown that ethnic minority patients have only a 37 per cent chance of finding a well-matched stem cell donor, compared with white patients having a 72 per cent chance.

There is a particular need for more young men to become stem cell donors because clinical data shows us that transplants from young, male donors are more successful as they provide the highest doses of healthy stem cells.

An estimated 75 per cent of people who go on to donate stem cells are males aged under 30 but only 12 per cent of people on the UK’s combined registry are from black or Asian background.

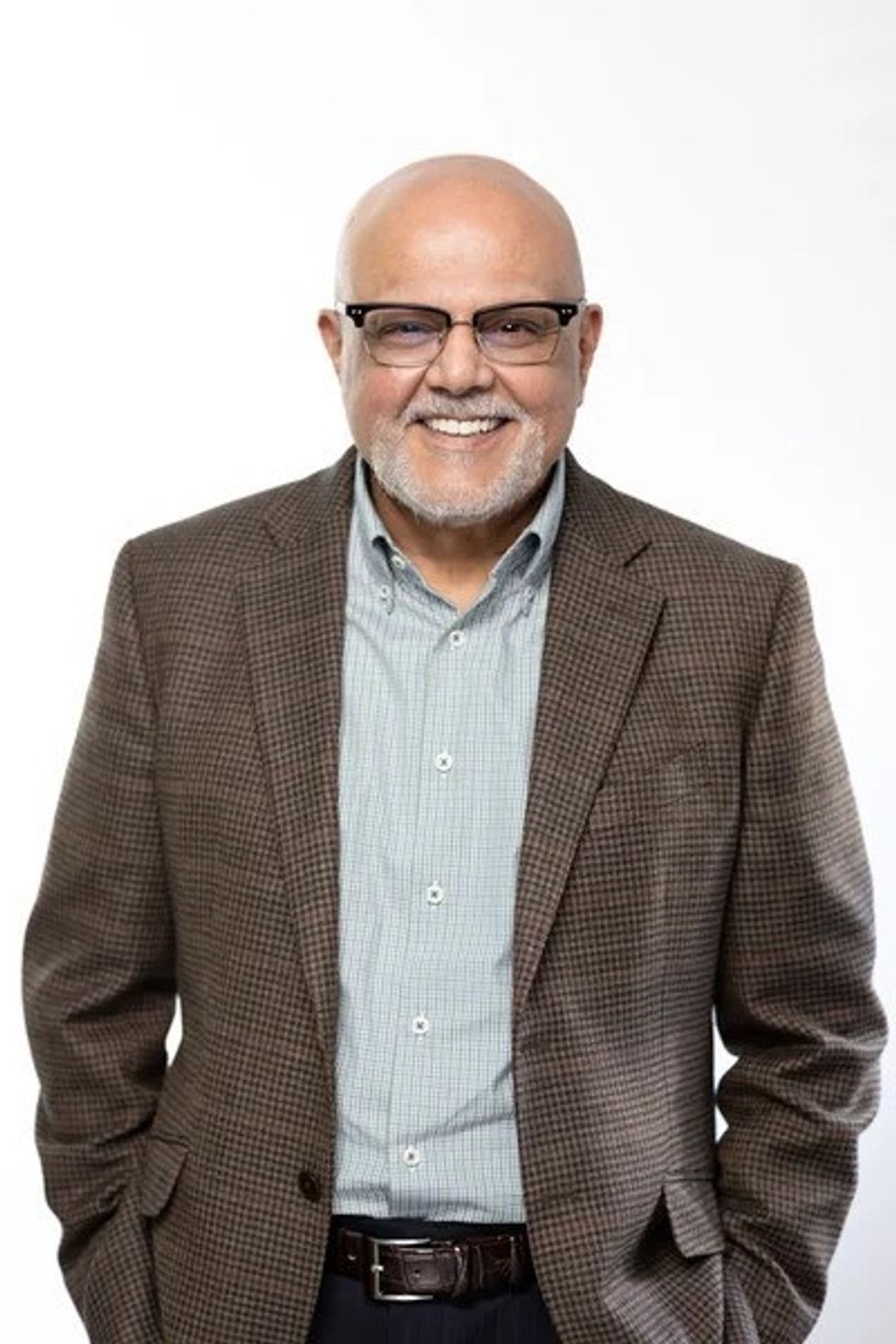

“Every offer to donate is valuable. But if you are a young black or Asian man, you are one of the most urgently needed people that we need to register as a potential blood stem cell donor. Your generosity and good health could save a stranger’s life,” said Dr Khaled El-Ghariani, consultant in haematology and transfusion medicine at NHS blood and transplant.

An inquiry by the all-party parliamentary group (APPG) for ethnicity transplantation and transfusion into organ donation in the UK found what it described as a “double whammy of inequity” faced by minority ethnic and mixed heritage people.

It revealed that people from black, Asian and minority ethnic communities are disproportionately affected by conditions such as sickle cell and kidney disease, making them more likely to require donors. However, they face a significant hurdle in finding suitable blood, stem cell, or organ matches on donor registers. Matching tissue types, a crucial factor for successful treatment, are more likely to be found among donors from a similar ethnic background.

The charity DKMS is the biggest stem cell register in the UK and have registered over million blood stem cell donors and helped to give over 2,500 people a second chance at life.

Hasnein Alidina, managing director (finance and operations) for DKMS UK told Eastern Eye that many people from ethnic minority backgrounds can’t find a compatible stem cell match due to under-representation on the stem cell donor register.

“We are working to ‘level up’ equality of access to stem cell transplants for patients in need from UK minority ethnic backgrounds by partnering with leaders in their communities to raise awareness,” said Alidina. Dr Jill Shepherd, senior lecturer in stem cell biology at the University of Kent, is leading a project to help address the inequality in stem cell transplants between white and black patients.

She has been running workshops with the local black community to give them a platform to voice their thoughts on barriers to stem cell donation and solutions.

Black donors make up only one per cent of the UK stem cell registry, meaning black patients are far less likely than white patients to find a suitably matched donor and get a transplant. “It is more difficult for people from ethnic minority backgrounds to find a matched, unrelated donor,” said Dr Shepherd.

People from a minority ethnic background are more likely to have a rare or even completely unique tissue type which can make it harder to find a fully matched unrelated stem cell donor.

“This is especially true for people of mixed heritage. Charities like Team Margot and DKMS are working in this area to try to recruit more donors from ethnic minority and mixed backgrounds,” said Dr Shepherd.

Dr Shepherd said not finding the best possible match was directly linked to the earlier deaths of ethnic minorities post stem cell transplant. “The key thing is to recruit more donors, and that’s where my team has been doing our work,” she said. “We’ve been particularly looking to speaking with people with black African heritage about these sorts of issues

“We’ve been working with a couple of local community organizations, the New Life Pentecostal church in Canterbury, and a group called Health Action Charity Organisation (HACO) in Medway. We’ve also done on campus workshops at the University of Kent with students.”

Dr Shepherd’s team are looking to work with south Asian communities next but it’s dependent on getting funding.

“Communication is first and foremost absolutely key. The relevant information needs to reach people and it needs to be sustained,” she said.