“MY POLITICAL journey was so quick,” former prime minister Rishi Sunak told Nick Robinson during a two-hour BBC podcast on his lessons from Downing Street.

Sunak’s meteoric rise and demise makes him a former prime minister at 44. Was it too much, too young? Did he make a mistake in grabbing a couple of years as prime minister after the implosion of Liz Truss?

Sunak cited his dharma – his sense of duty – as the reason to serve, acknowledging that being unelected meant he never quite had the full authority of the role. Was he dealt an all-but-impossible hand – or did he play it badly? Probably both. Any successor to Truss would have needed a miracle to secure more than a halfterm in office. Yet Sunak made unforced political errors that contributed to his landslide defeat.

He is now the youngest former prime minister since William Pitt the Younger left office at 42 in 1801. Sunak laughed off the idea he might one day get back to Downing Street. “I don’t want being prime minister to be the only thing that defines me professionally,” he told Robinson.

His best model could be William Hague, his constituency predecessor in Yorkshire, who was a failed party leader at 40, but has had several careers since – as an author, foreign secretary and now the chancellor of Oxford University.

Sunak’s biggest policy impact in office came not as prime minister, but as a rookie Covid chancellor. The furlough scheme gave economic security to many millions at a time of mass uncertainty. That is ironic – since the BBC interview captured Sunak’s Thatcherite aspirations to be a taxcutting small-state Tory. He would not put the net zero climate target in law. He would invest in defence, but slash billions from benefits. He declared against Louise Casey’s attempt to build consensus on social care.

“Do we as a country think it’s right to pay more taxes for a more generous social care policy?” he asked Robinson. “I personally think the answer is no.”

Sunak regretted raising expectations in how his pledge to ‘stop the boats’ was communicated – this gentle interview did not interrogate that he had never believed Rwanda could work when he was chancellor.

He governed as a prisoner of his party – explaining he reappointed Suella Braverman as home secretary to try to keep a “big tent” – but could not control it. His reasoning for his summer election – ending his time in Downing Street several months before he had to – claimed he still hoped to win it, but it was essentially a choice of suicide by electorate, with an ungovernable party going increasingly mad.

Braverman’s animus towards Sunak may partly explain her ill-judged to decision to come in behind podcaster Konstantine Kisin – who made the ill-informed, ugly claim that Sunak is too “brown and Hindu” to ever qualify as English – to say that she and he could never hope to qualify.

“Of course, I’m English – born here, brought up here,” Sunak said. His graceful riposte to what he called Braverman’s “ridiculous” argument noted the irony of those who claim to want integration declaring this form of it may be impossible for five generations. “It is not enough to support England – it turns out it might not even be enough to play for England, at football or cricket, on this definition.”

What was Suella thinking? She has a subjective certainty that, if she does not feel English, this how everybody else sees it. In the 1970s, both Commonwealth migrants and the white British made her distinction between a civic British citizenship, that could be multi-ethnic, and a narrower English identity. English-born minorities felt they could be both. Black players playing football for England for half a century means there has been a common sense consensus that you do not have to be white to be English for 30 years, at least.

The impact of sporting symbolism may be why the English identity of the Sunak and Patel generation is perhaps less familiar. It seems ironic and regressive, as Robinson noted, for Sunak’s ethnicity and faith to now become a greater focus after his premiership than it was during it.

But, ultimately, the most important legacy of Sunak’s premiership is a symbolic one. He likes to emphasise how little was made of his ethnicity or faith. “It is worth noting it as notable but not that notable,” he says.

Asian and black chancellors, home secretaries and foreign secretaries – unknown before 2018 – have become remarkably frequent. The leader of the nation is different. So it was good that Sunak became prime minister, even if he was handed a poisoned chalice electorally.

What his short premiership shows is that no sphere of political, economic or cultural power in this country should set any ceiling to how high British Asian talent can rise.

Sunder Katwala is the director of thinktank British Future and the author of the book How to Be a Patriot: The must-read book on British national identity and immigration

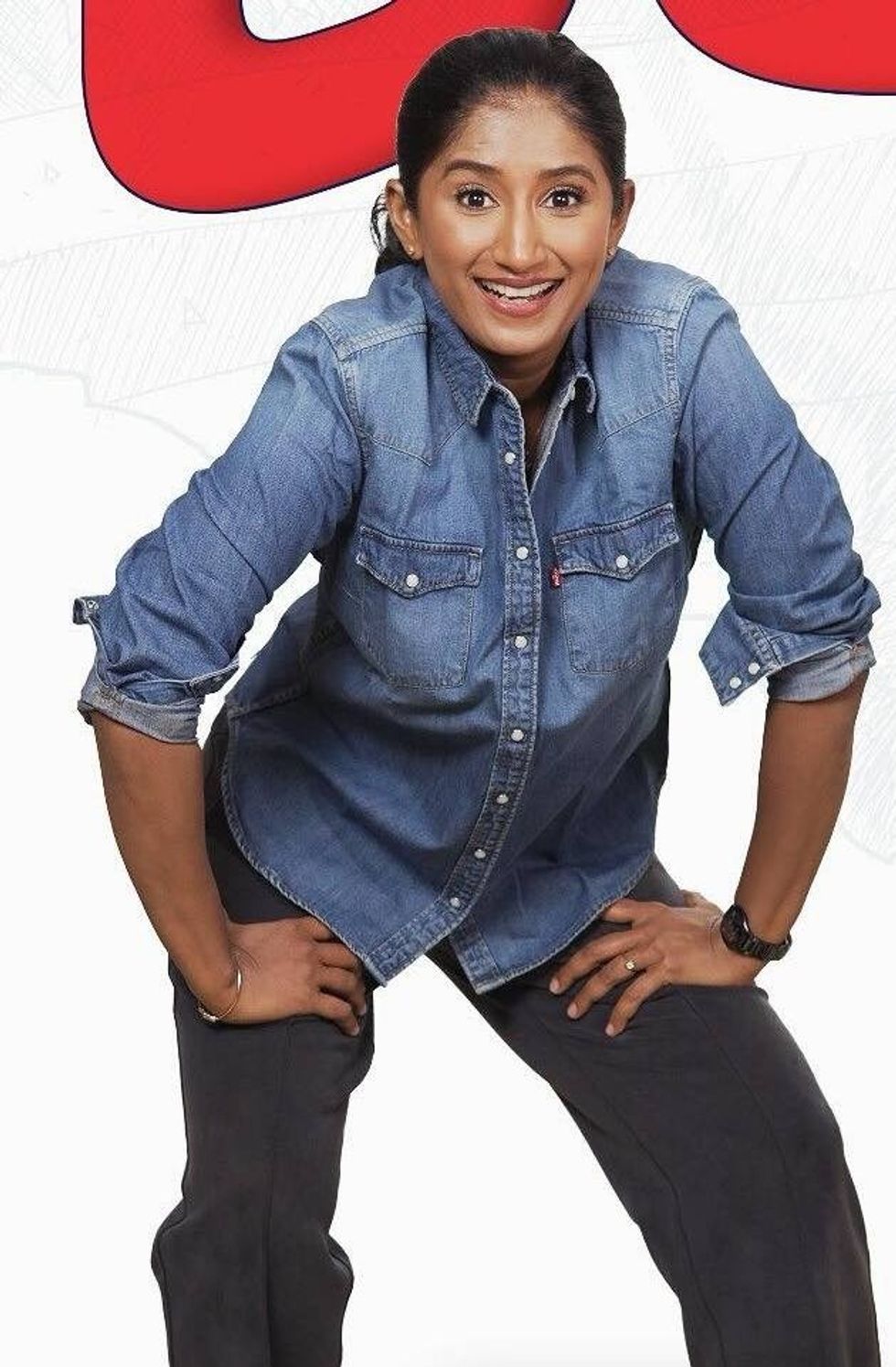

Shraddha Jain

Shraddha Jain Arundhati Roy

Arundhati Roy William Dalrymple and Onjali Q Rauf

William Dalrymple and Onjali Q Rauf Ravie Dubey and Sargun Mehta

Ravie Dubey and Sargun Mehta Money Back Guarantee

Money Back Guarantee Homebound

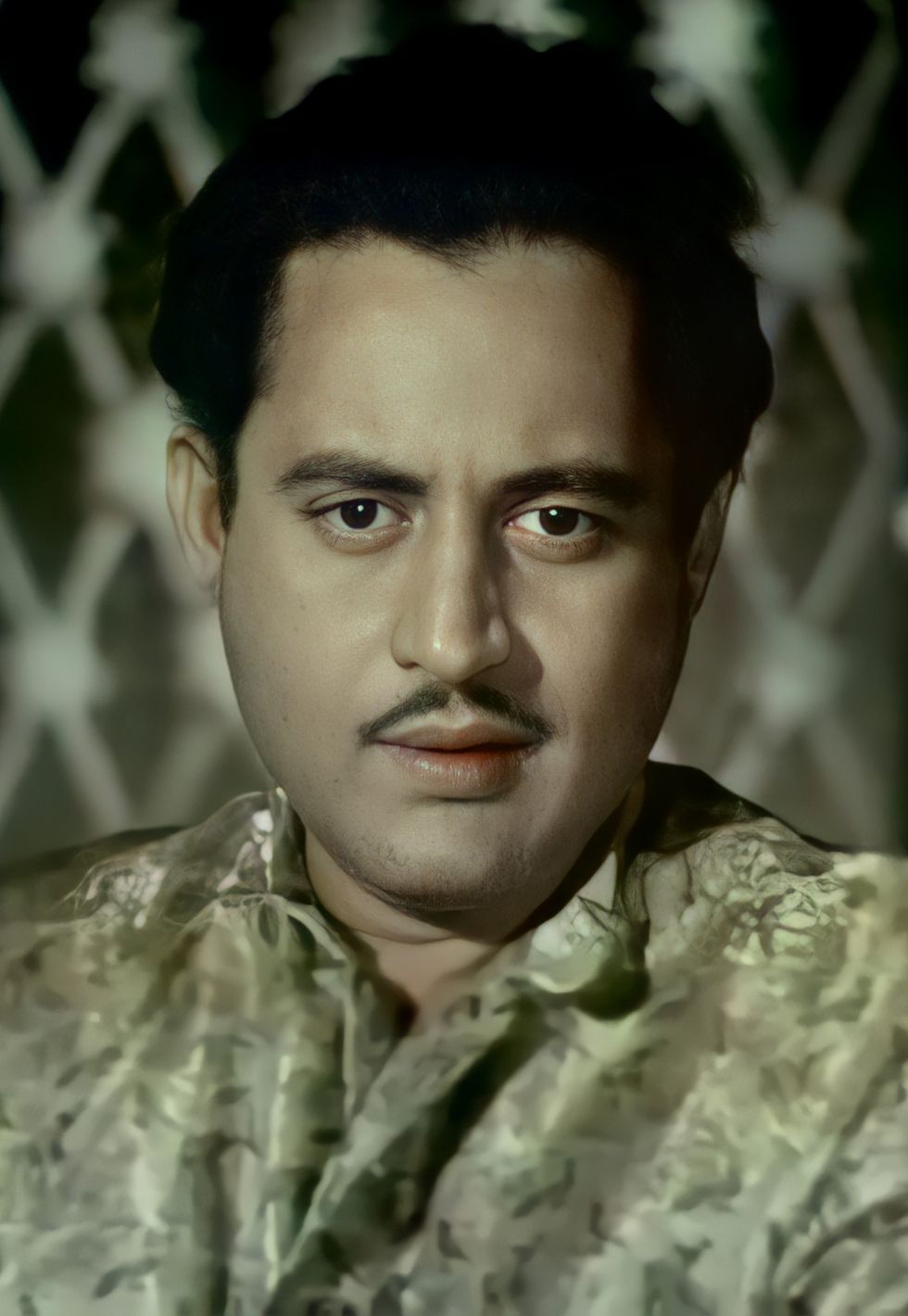

Homebound Guru Dutt in Chaudhvin Ka Chand

Guru Dutt in Chaudhvin Ka Chand Sarita Choudhury

Sarita Choudhury Detective Sherdi

Detective Sherdi

Doctor Who

Doctor Who Aishwarya Rai Bachchan

Aishwarya Rai Bachchan  Mohini Dey

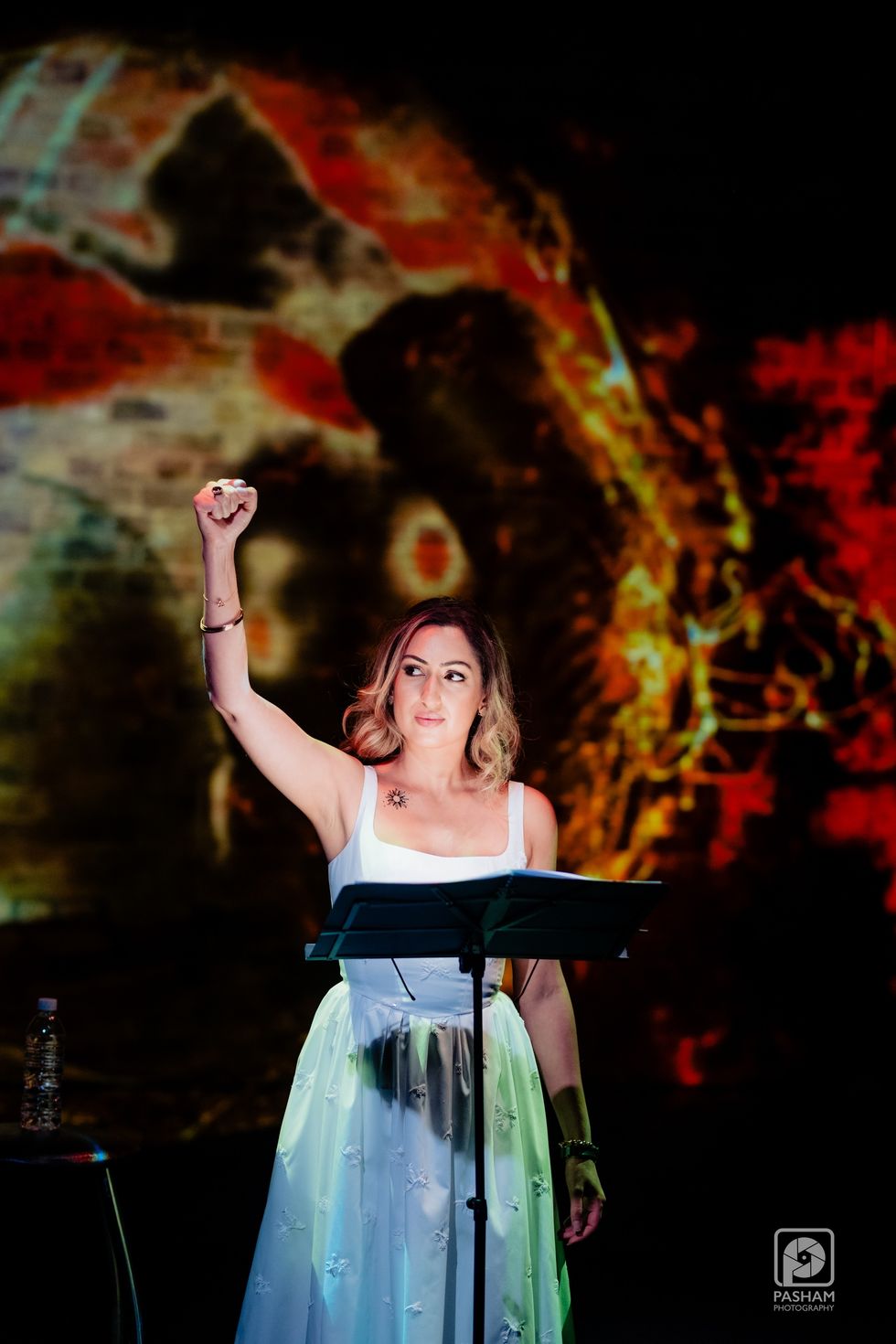

Mohini Dey Queen of Wands

Queen of Wands Kabhi Main Kabhi Tum

Kabhi Main Kabhi Tum  Raja Shivaj

Raja Shivaj Suswagatam Khushamdeed

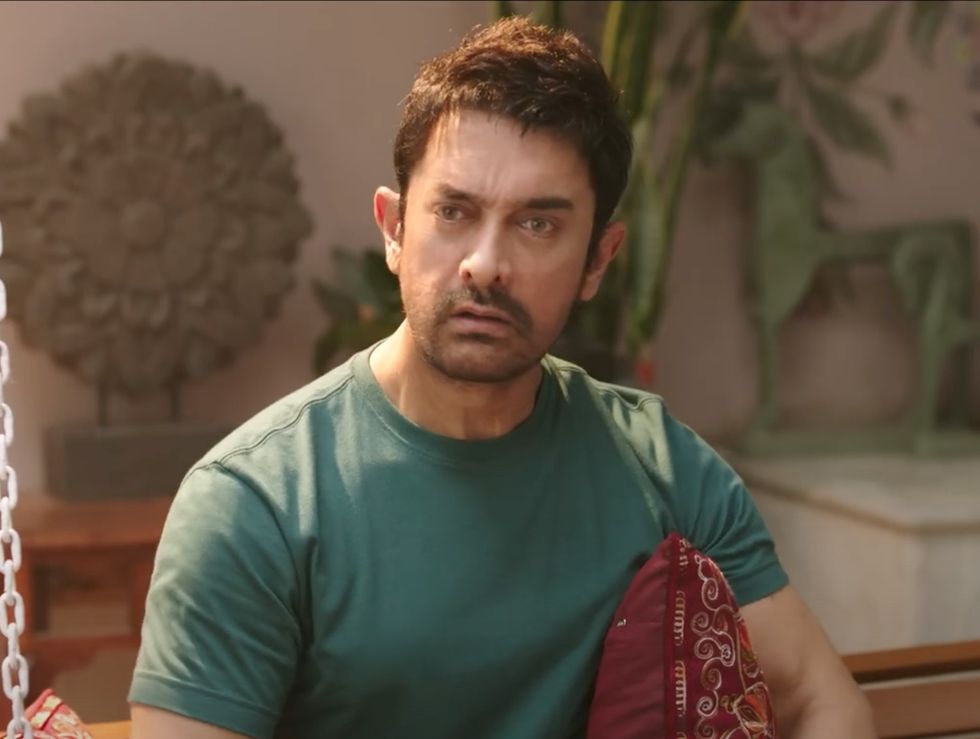

Suswagatam Khushamdeed Sitare Zameen Par

Sitare Zameen Par Arijit Singh

Arijit Singh Sneha Shankar

Sneha Shankar