THE yoga craze hit east Asia in a big way but took a temporary hit from a pandemic called SARS.

After the threat ended, in 2003, I resumed my search for yoga classes like many others in Hong Kong, and within a week, I signed up with a centre offering a variety of yoga classes, taught by teachers from India. I got a membership limit of five classes per month.

After finishing my third class in my first month, I walked past another room and through the glass saw people jumping around. They were moving their arms and legs, with a foreign song playing in the studio, and they all had a certain look on their faces. They were all smiling and having fun.

This sense of joy was, in some ways unusual, as we live in a fast-paced and crowded city of eight million and are always busy making money and definitely too busy to smile. (We ranked consistently around 70 out of 150 countries since the UN published its World Happiness Index in 2012).

I wanted to be part of this experience. Two days later, I was in a class called Bollywood Dance, taught by a teacher from India. I distinctly remember the first song was Chaiyya Chaiyya from the film Dil Se. The melody was beautiful and sounded very different to the music I was used to. The choreography was graceful and fun. To put it mildly, I was instantly hooked.

That started a long love affair with Bollywood dance. Not long after, I upgraded my membership to unlimited number of classes to fuel my addiction. Dance would pretty much be the only thing I did other than work. My family thought I had joined some kind of cult.

Some 18 years and 60 days later, I am still learning and appreciating what Bollywood dance is and what it has given me – an awareness of rhythm, movement and control of every muscle. The emotions and combination of these with the music into the mind, body, and soul are indescribable. The expression and experience are unique each time. It is just magical.

Bollywood dance led me towards Hindi movies, and Indian classical dance forms like Bharatanatyam. It fuelled my appreciation for Carnatic and classical Hindustani music. It also drew me towards Indian arts, festivals, cuisine, people and travelling to the country.

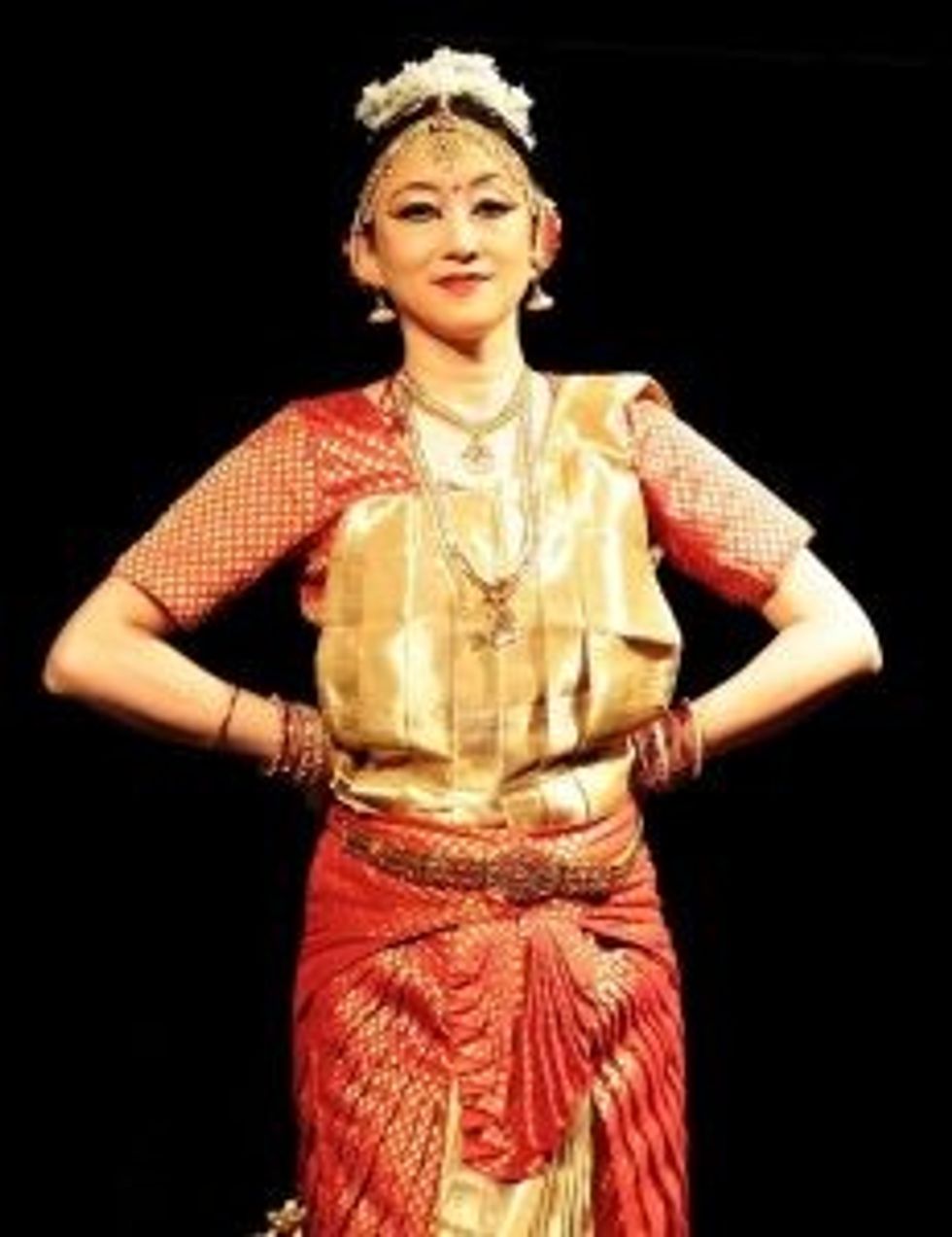

When I started, I never thought I would perform Bollywood dance and Bharatanatyam on stage, but miraculously I did, and I do. I never imagined visiting the Kalakshetra Foundation in Chennai, teaching Bollywood dance part-time and participating in the first Bollywood movie made in my home city.

Did all these happen accidentally or by some divine intervention? It is a blessing to have met wonderful friends, fellow dancers, great teachers, choreographers, actors, and performers from around the world through dance. Collaborating with different dancers, artists, and community leaders to share the joy of Indian dance with diverse audiences continue to provide me with a source of inspiration and happiness.

Jai Hind.

Teresa Cheung is a Hong Kong-based accountant who is also a dancer and fan of Indian culture. She also enjoys taking photographs of sunsets and clouds and

loves elephants.