EASTERN EYE readers should definitely see The Merchant of Venice 1936 at the Trafalgar Theatre in Whitehall.

When Shakespeare wrote his play between 1596 and 1598, it seems he anticipated what Robert Jenrick would say in 2025. Shylock, the moneylender, is derided as an “alien” – yes, that exact word.

It is easy for an audience to imagine Shylock, the Jew, replaced by a Pakistani, who explains why he is demanding his “pound of flesh” cut out from Antonio’s Christian heart as stipulated in the legal bond: “If it will feed nothing else, it will feed my revenge. He hath disgraced me, and hindered me half a million, laughed at my losses, mocked at my gains, scorned my nation, thwarted my bargains, cooled my friends, heated mine enemies, and what’s the reason? I am a Muslim.

“Hath not a Muslim eyes? Hath not a Muslim hands, organs, dimensions, senses, affections, passions? Fed with the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject to the same diseases, healed by the same means, warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer, as a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed? If you tickle us, do we not laugh? If you poison us, do we not die? And if you wrong us, shall we not revenge?

“If we are like you in the rest, we will resemble you in that. If a Muslim wrong a Christian, what is his humility? Revenge. If a Christian wrong a Muslim, what should his sufferance be by Christian example? Why, revenge. The villainy you teach me I will execute, and it shall go hard but I will better the instruction.”

Just replace “Muslim” with “Jew” to return to the original. This speech, one of the most important in the entire Shakespeare canon, is at the centre of The Merchant of Venice.

And contemporary British politics. One can also imagine various right wing politicians prancing around on stage in black shirts and wearing arm bands, decreeing not that the Muslim become a Christian – as is the sentence for Shylock – but be forced to take out membership of the Reform party. With due apologies, it would not be too difficult to write in parts for the likes of Jenrick, Kemi Badenoch and Nigel Farage.

Of course, all this is a bit fanciful, but we are in the makebelieve realms of theatre and in a land where free speech and artistic freedom are cherished.

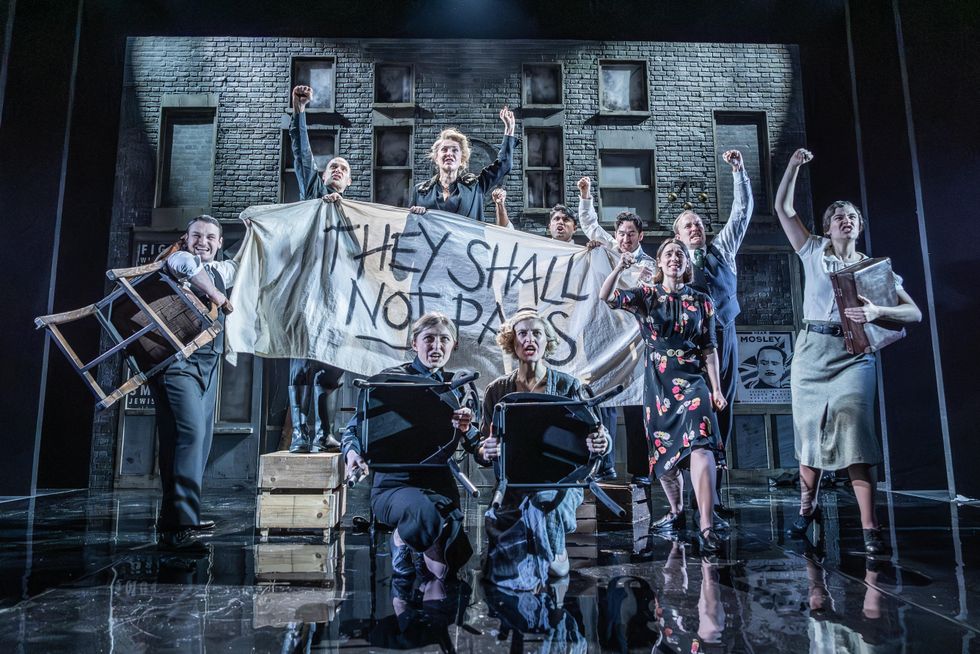

In the production at the Trafalgar Theatre, Shakespeare’s play is transposed from Venice to the East End of London in 1936. This is when Sir Oswald Mosley and his British Union of Fascists demonstrated against Jewish settlements in the East End, protected by the police (much like what happened when the National Front marched through Southall in the 1970s). In the famous battle of Cable Street, the fascists were resisted by what would today be called “woke” forces.

The play leaves out a few Somali Muslim sailors who joined the resistance.

TracyAnn Oberman gives a stunning performance as Shylock, a Jewish woman moneylender. Hers is a much more sympathetic characterisation of Shylock. Perhaps that is what Shakespeare intended. The play has been adapted by Oberman and the director, Brigid Larmour.

The programme contains a director’s note which says this production began as a conversation in 2018. “Tracy told Brigid she wanted to play Shylock as an East End matriarch in the 1930s, inspired by her greatgrandmother Annie and other workingclass Jewish matriarchs in the East End, who escaped the violent anti Jewish pogroms in the countries of the Russian Empire and thought of London as a safe haven.

“Brigid was excited by the opportunity this gave to frame the problematically antiSemitic characters of Portia, Antonio and Gratiano as British fascists of that time. Choosing the year 1936 would enable a very different ending for Shylock’s story, in the context of the Battle of Cable Street. This production gives us a chance to address contemporary issues of antiSemitism and prejudice.”

Given the passions raised by the IsraelGaza war, a traditional rendering of Merchant would have been problematic.

There is also a paragraph on the “historical context” which has a resonance to today’s politics: “During the 1930s, Britain had an active Fascist party, the British Union of Fascists, led by (Sir) Oswald Mosley. As it doesn’t fit within our national myth that ‘Britain stood alone’ against Hitler in 1940, this inconvenient truth is often forgotten. Mosley’s marriage to the beautiful socialite Diana Mitford actually took place at the house of Goebbels, Hitler’s propaganda minister, and Hitler was an honoured guest. Mosley’s ideas, and those of Hitler and Mussolini, appealed to a wide cross section of English society, from ‘leftbehind’ veterans of the First World War unemployed in the Great Depression, to aristocrats fearing the spread of egalitarian ideas from Soviet Russia would lead to social disorder and their own removal from power.”

In an essay on “Female Jewish Moneylenders”, Rebecca Abrams, author of The Jewish Journey: 4000 Years in 22 Objects, makes the point that “Shakespeare’s Jew (the most famous in Western literature with the possible exception of Leopold Bloom in James Joyce’s Ulysses) has continued to serve – adapted over the centuries to meet the fashions and prejudices of wildly different productions, from the philosemitic to the rabidly antiSemitic. The play was staged multiple times in Germany in the 1930s, with Shylock cast as the exemplar of the monstrous Jew and justification for the Nazi regime’s own monstrous antiJewish ideology.

“Whatever Shakespeare’s intention, Shylock has undoubtedly served to embed in popular imagination a negative stereotype of the Jewish moneylender as rich, rapacious and male.”

The splendid Mikhail Sen (who was Amit Chatterji in Mira Nair’s BBC TV adaptation of Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy), plays Lorenzo, a friend to Antonio (Joseph Millson) and Bossanio (Gavin Fowler).

Lorenzo, a Christian, is brave enough, to romance and marry Shylock’s daughter, Jessica (Grainne Dromgoole). Instead of the Prince of Morocco, who fails to win the hand of Portia (Georgie Fellows), Mikhail also does a wonderful cameo as the Maharajah (“Dislike me not for my complexion”), who chooses the gold box and is rejected as a suitor. Naturally, Bossanio wins because he is cast as an “Englishman”.

Portia, dressed as the young male lawyer who saves Bossanio from Shylock’s knife, delivers the other famous speech in Merchant (which we had to memorise at school in India): “The quality of mercy is not strained;/ It droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven/ Upon the place beneath. It is twice blest;/ It blesseth him that gives and him that takes.”

But in the final courtroom scene, when Shylock is outwitted – she cannot spill a drop of Christian blood – Portia, Bossanio and Antonio and the local policeman all wear blackshirts. Shylock is spat on, has water thrown in her face, has her property confiscated and is repeatedly called “Jew, “Jew”, “Jew”.

To be sure, the grooming gangs are to be condemned in the strongest possible terms, but today, it is “Pakistani”, “Pakistani”, Pakistani”, “Muslim”, “Muslim”, “Muslim”.

The Merchant of Venice 1936 is at the Trafalgar Theatre until next Saturday (25), before going on tour to Liverpool, Bath, Leeds, Salford, Fareham, Cardiff, Southend and Birmingham.

Mythili Prakash

Mythili Prakash Prakash in She’s Auspicious

Prakash in She’s Auspicious

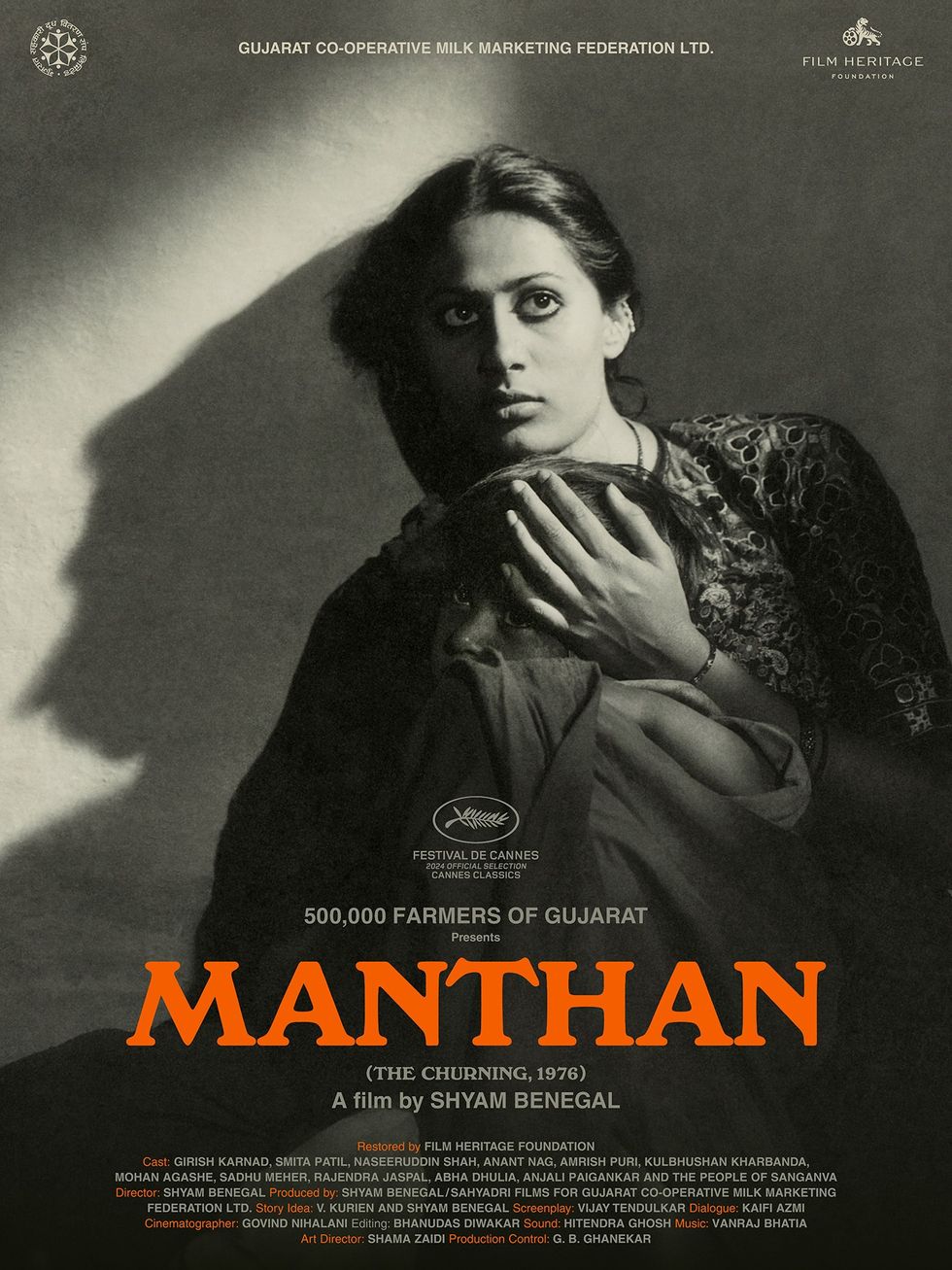

A scene from Ankur (1974)

A scene from Ankur (1974)

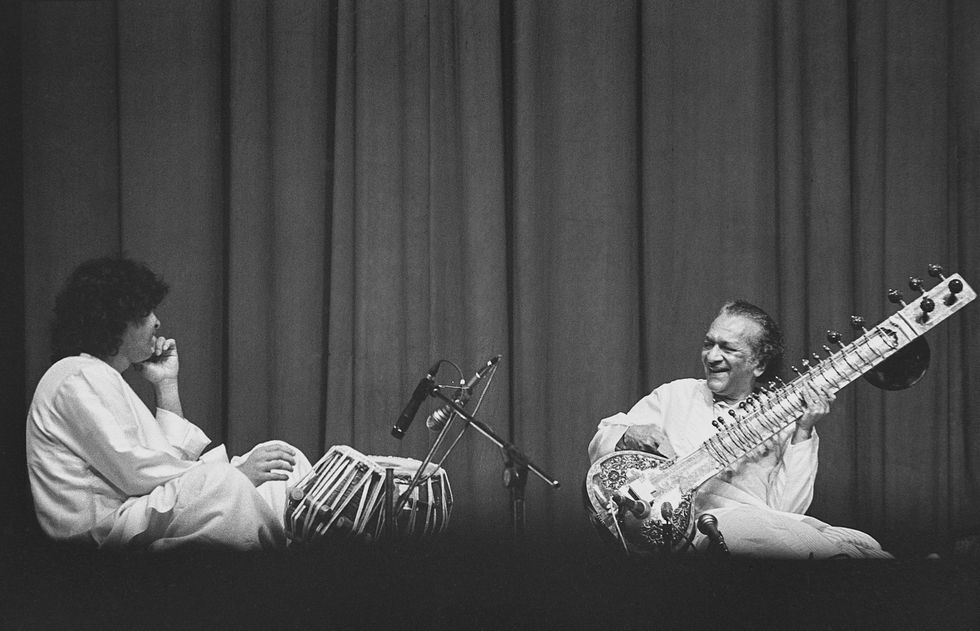

With flautist Pandit Hariprasad Chaurasia in 2023

With flautist Pandit Hariprasad Chaurasia in 2023 With his wife Antonia Minnecola and daughter Anisa Qureshi with sitar maestro Ravi Shankar

With his wife Antonia Minnecola and daughter Anisa Qureshi with sitar maestro Ravi Shankar  Shankar Mahadevan, Hussain, V Selvaganesh, and Ganesh Rajagopalan after winning the Global Music Album award for This Moment in 2024

Shankar Mahadevan, Hussain, V Selvaganesh, and Ganesh Rajagopalan after winning the Global Music Album award for This Moment in 2024