WATCHING the funeral of the late Queen, I wondered why her son Charles, the new King, somehow seemed to resemble an actor playing the role.

This was partly simple unfamiliarity. Nobody aged under seventy can remember there actually being a King before. It may have been a function of familiarity too. Charles’ long apprenticeship as Prince of Wales means many fictional Kings on stage and screen over the last half century have been modelled on his persona. Decked out in military dress, wearing his medals and sword, the King resembled those staged performances.

Costume and ceremony play a big part in the symbolic role of a monarchy. May’s Coronation will be the first edition in this century of a tradition dating back over ten centuries. This Coronation takes place in a different society from that of 75 years ago. “Charles at odds with Church over diverse Coronation” was a Mail on Sunday splash headline, reporting former Tablet editor Catherine Pepinster’s report that a tug-of-war over the role played by minority faiths had delayed the order of service.

This plural, somewhat disunited Kingdom has acquired a multiculturalist King, eager to ensure that an increasingly diverse Britain feels invited to this national occasion.

Professor Tariq Modood, the leading academic theorist of multiculturalism in Britain, recognises a kindred spirit in this multiculturalist King. Charles’s decades of engagement across faiths was reinforced by his using one of his first public statements, after his accession last Autumn, to declare his sense of a ‘duty to protect the diversity of our country’.

Charles has often spoken of Britain as a ‘community of communities’. The King may now emerge as Britain’s most prominent champion of multiculturalism, after two decades when the term has fallen somewhat out of political fashion. That was a complex story. The same word often meant different things to different people: for some it was simply the positive recognition of the new reality of a multi-ethnic society. Yet for others it was too relativist and risked going beyond recognising difference to actively incentivising it, at the expense of efforts to find common ground. The constitutional constraints on the Monarch mean that Charles must float above politically contested debates about inclusion and integration policy – but he can legitimately help to set the tone in which they take place.

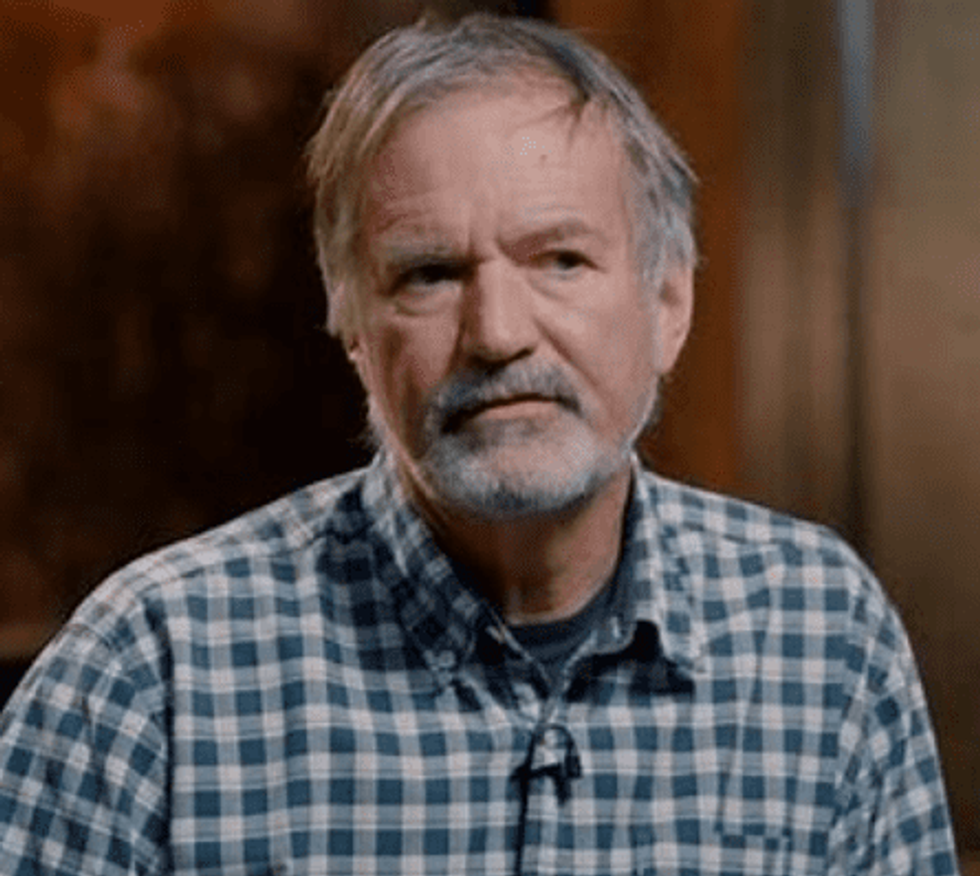

Those with differing views of the politics of multiculturalism can see value in what the King is trying to do. David Goodhart, who has written sceptically about the limits of multiculturalism, sees potential in the King’s emphasis on recognising minority contributions. The King, born in 1948, marks a shift to the generation which grew up with a changing Britain. “The Queen engaged with race primarily through the Commonwealth abroad. It may be Charles’ role to bring that home,” Goodhart tells me. Since politicians are struggling to bridge Britain’s identity divides, the Monarchy’s symbolic power could reach across them, he says, as long as it can signal an increased recognition and inclusion of minority faiths in ways that can keep Anglicans onside.

My local vicar, the Reverend Edward Barlow in Bexley, told me that many in the Church believe it should play a bridging role to promote the common good: “One approach is to acknowledge that, as the Established Church, we have privilege and can use this to create a platform for minority groups, usually to the end of community cohesion”. That does not involve the King sacrificing the integrity of his own faith. “My compering a recent Iftar during Ramadan does not mean I have suddenly converted to Islam,” he says.

What Modood and Goodhart both note is that religious minorities seldom contest the role of the Church of England as an Established Church, reflecting a preference for securing religion’s place in public life in an increasingly secular age. Minority faith leaders say they are relaxed about attending a Christian Coronation service. The King today has a more evolutionary, gradualist agenda than his initial 1990s idea of styling himself as ‘defender of faith’, emphasising both his commitment to the Established Church and his desire to reach beyond it too, taking care to acknowledge humanist and secular principles as well. That he wears different hats – as Supreme Governor of the Established Church, and head of state of a society of many faiths and none – gives him different opportunities to engage.

The census showed that all faiths in Britain are a minority now. “The Coronation and its public reception will be a test of whether we have evolved from an Anglican establishment to a more egalitarian, diverse and inclusive – in other words, a multiculturalist – understanding of religion and state in Britain today,” Modood tells me. Recognising the multi-faith presence in modern Britain should be something that this Coronation ceremony and broader celebrations can achieve without any great culture clash or political controversy. Reaching out across generations in this increasingly secular society may prove the greater long-term challenge.

The multiculturalist King

The King can legitimately help to set the tone in which the politically contested debates about inclusion and integration policy take place, says the expert