If somebody of soaring public ambition ever seeks your advice on how to become Prime Minister, history suggests one obvious starting point: get elected to lead the Conservative Party.

Every single Tory leader from 1922 until 1997 got to Downing Street – until that pattern was broken by William Hague, Iain Duncan Smith and Michael Howard in quick succession. Whoever wins this 2024 leadership contest is less likely to find themselves Prime Minister in five years’ time than to join that unhappy club of Tory leaders who didn’t quite make it.

Who will be the next leader is the dominant question among Conservatives at their first party conference since their election hammering. The question many outside the party are asking may be: how much does it matter anyway?

This Birmingham party conference is a showcase to test the four leadership contenders before MPs knock two out, leaving party members to choose a leader from the two finalists. Robert Jenrick came to Birmingham as the frontrunner for two reasons: that he is the sole member of the quartet who is almost certain to make the final ballot – and because Kemi Badenoch seems unlikely to hang on to second place to face him.

Pre-conference polling of party members by Conservative Home finds Jenrick would start with a 27-point lead against Tom Tugendhat, double his 14 per cent advantage against James Cleverly. He currently trails Kemi Badenoch by 13 percentage points, so would become the underdog against her.

A tiny parliamentary party - just 121 MPs – makes the run-off hard to predict. The votes of one-third of MPs guarantee a ballot place. Second or third preferences will decide who makes it into the final two. Over a third of MPs – at least 37 – will choose again when their candidate gets eliminated.

Robert Jenrick, on 33 votes, is almost through. Kemi Badenoch, on 28 votes, is worrying out loud about a Westminster “stitch-up” if MPs don’t put her through as the members favourite.

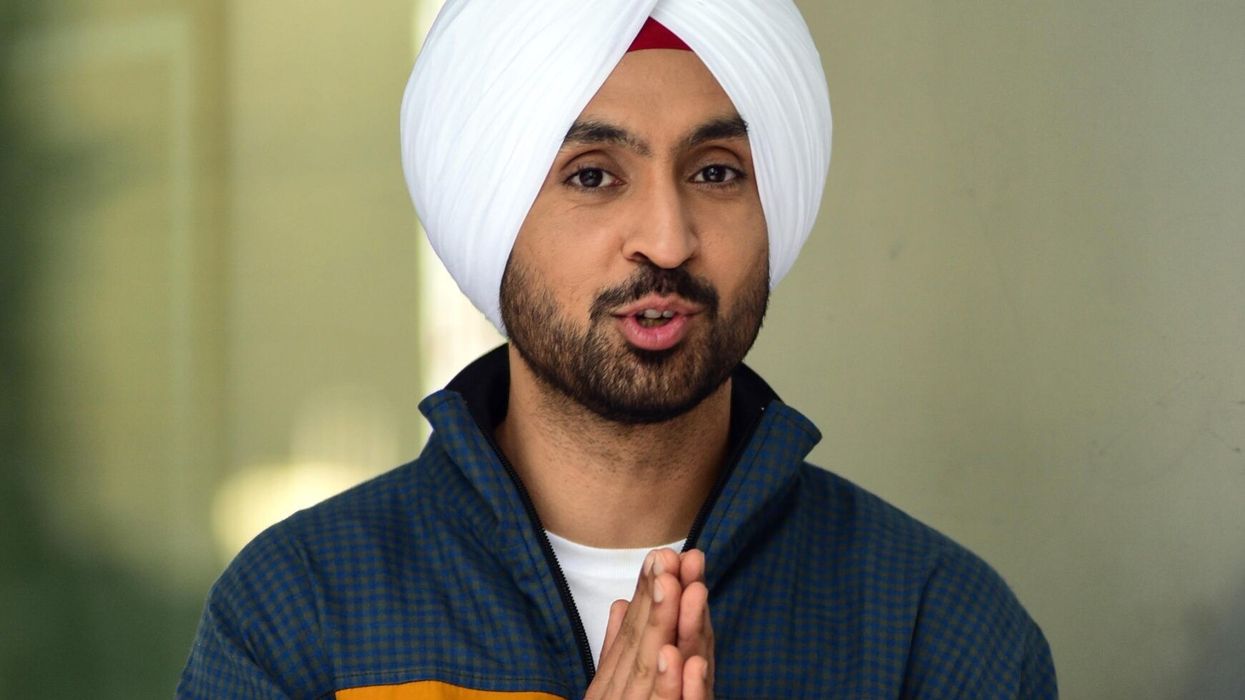

Britain's main opposition Conservative Party Shadow Housing, Communities and Local Government Secretary Kemi Badenoch hugs a delegate on the second day of the annual Conservative Party Conference in Birmingham, central England, on September 30, 2024. (Photo by HENRY NICHOLLS / AFP) (Photo by HENRY NICHOLLS/AFP via Getty Images)James Cleverly and Tom Tugendhat, both on 21 votes, are now in a head-to-head elimination battle to become the “stop Kemi” candidate. Whoever survives the next round might overtake Badenoch by converting the other’s voters. Yet Badenoch could pitch herself to MPs as being the “stop Jenrick” candidate instead – if she could win over a dozen more centrist MPs, from supporters of Mel Stride, or whoever gets knocked out next. Yet Badenoch’s opening interventions at this conference – questioning whether those from all cultural backgrounds could integrate equally into British identity, and a muddled interview criticising maternity pay – have probably made her Westminster challenge harder.

This contest has been more about personality than party strategy or policy., though the candidates do have different priorities. Tugendhat made his name on foreign policy. Badenoch is best known for wanting conservatives to take a robust line on identity issues. Jenrick has reinvented his politics over immigration and asylum. But there are few policy arguments. All four candidates have said what they think party members want to hear – influenced by how Rishi Sunak lost to Liz Truss after criticising the tax plans which were to implode so spectacularly.

This quartet stand for lower taxes – but defend a universal winter fuel payment to pensioners. They want the state to do less, better – but with more emphasis on higher spending on defence, prisons and policing than on what to cut back from. Badenoch opposes the smoking ban and a football regulator as excessively statist projects bequeathed to Labour.

Jenrick says the Conservatives were wrong to accept the New Labour legacy of Equalities, Human Rights and Climate Change Acts, and wants to leave the European Convention on Human Rights. Tugendhat – somewhat implausibly – says he would be prepared to do so too, as a last resort.

Keir Starmer gives the new Tory leader hope. He made it to Downing Street in one term himself, after succeeding Jeremy Corbyn; and Starmer’s stuttering start as Prime Minister makes the new Opposition leader’s task less hopeless than that facing William Hague in 1997.

Yet the Conservatives look in deeper trouble than Labour in 2019. Their MPs are outnumbered more than three-to-one-, and the-party membership is ageing and shrinking. The next leader must win back many of the voters lost to Nigel Farage’s Reform party while also winning back most of the 65 seats lost to the Liberal Democrats in the new “Yellow Wall” across the south of England and bridging the generational gulf in the party’s vote. It may take a minor political miracle to achieve all of that in one term – yet David Cameron’s four successors as Tory leader since 2016 have only lasted an average of two years. The next leader – announced on November 2nd – will need to prove this once-glittering prize in British politics is not now a poisoned chalice.

(The author is the director of British Future)

And , the the cover of her book.

And , the the cover of her book.