by LAUREN CODLING

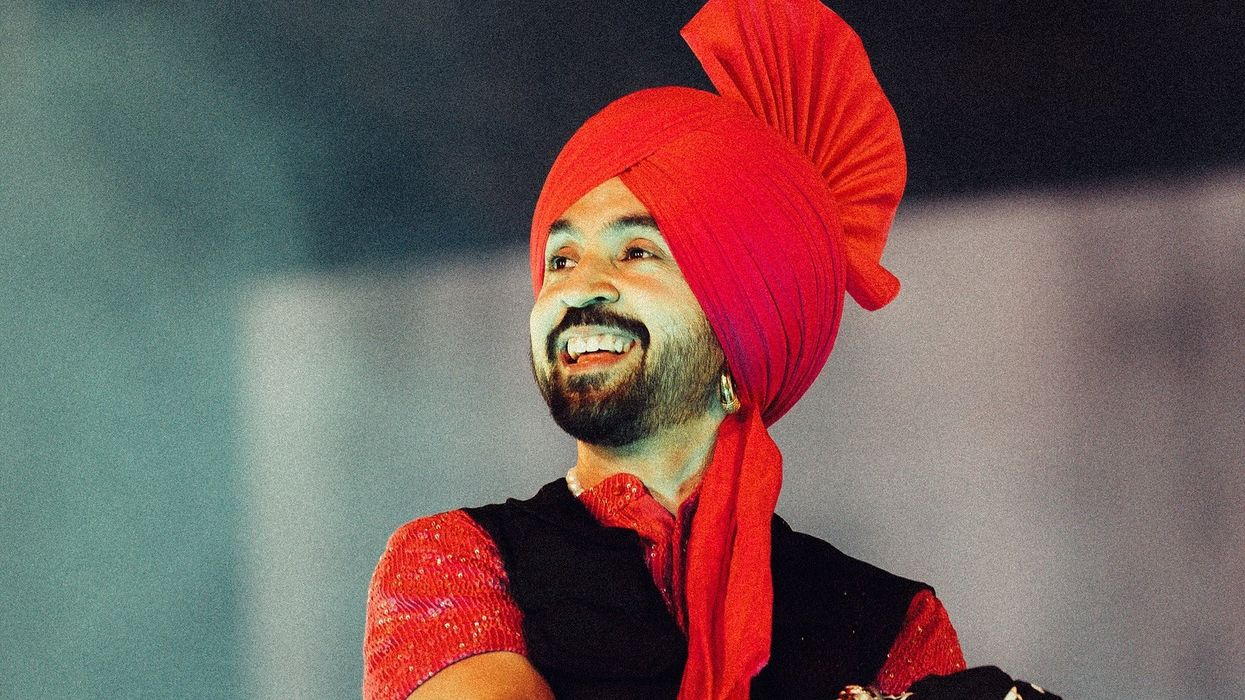

A “POWERFUL” book hoping to showcase the identity and culture of turban-wearing Sikhs was launched this week by a pair of award-winning Asian photographers.

Turbans and Tales is a collection of portraits of modern-day Sikhs by Amit and Naroop, two critically acclaimed artists who have worked with Riz Ahmed and Ricky Gervais.

The duo, full names Amit Amin and Naroop Jhooti, have put together 72 striking images of Sikh men, women and children in turbans across the UK and the US. The book, their first, aimed to “define what the modern Sikh identity represents”.

The subjects chosen to appear in the photographs were all from various backgrounds and generations.

Some were aspiring footballers and kickboxers while others worked in politics or medicine.

Each photograph is accompanied by personal stories of what the turban meant to the individual.

Ahead of the book launch on Thursday (24), Naroop told Eastern Eye he believes the project has helped Sikhs “have a different relationship with their identity”.

Since 2014, the portraits have toured galleries in London and New York, and are still

being exhibited globally.

As the photographs attracted interest, a museum curator once told the collaborators that turbans appeared to be less toned down by those who wore them.

“Our project can’t take full credit, but a lot of younger guys tend to wear more flamboyant

turbans now, which is something we’ve never seen before,” he said. “They want to stand out and look different and that is the new face of the Sikh identity.

“They are proud of the way they look, and they don’t feel they have to conform.”

Noting the similarities and differences between the subjects, Naroop said he was interested to hear the contrasting experiences between British and American Sikhs.

Older British Sikhs spoke of the persecution they faced when they first arrived in the

country, but the younger generation did not dwell on this as much as they felt accepted in British society, he revealed. They spoke of how they loved their turban and how much it had empowered them.

In the US, however, Sikhs described their daily struggle of living with the turban because of the discrimination they faced.

“They said their turbans and beards aren’t as understood in American society,” the British-born photographer said. “They talked about fighting for opportunities.”

Naroop added although there has been progress, the fight for equality was an ongoing battle, and he hoped that the book would help clear “misunderstandings” about the turban.

For instance, historically, the turban was not worn only by Sikhs, but also by people in other religions and cultures. People fought for the turban and died for it, Naroop noted.

In 1658, when the Mughals ruled India, emperor Aurangzeb used the turban as a way to segregate the population. If a non-Muslim wore a turban, they were killed.

“The reasons Sikhs took to it (the turban) was in defiance of the effective rule,” Naroop explained. “They wanted to show that everyone should be treated equally and have the same privileges, as one of the main tenets of Sikhism is equality.

“Everybody should trace their own history and see how important it was to their own religion.”

Having photographed a number of celebrities, the pair found working with inexperienced subjects posed a new challenge.

“None of these guys had ever had a professional photo shoot. So, for them, it was quite daunting and nerve-wracking,” Naroop said.

“We had to create an image that looked natural, but was striking, and [where] the subject

didn’t look nervous.”

When they worked with elderly men, they found some preferred to speak Punjabi.

While Naroop is fluent in the language, it was a challenge for Amit.

“His usual wit and charm didn’t work on them” Naroop joked. “I had to step in and translate, which could be pretty amusing to do.”

Amit and Naroop, who are cousins, grew up together in Southall, west London.

They lived on the same street and enjoyed a close relationship.

Growing up, their Sikh grandfathers sported the turban, taking pride in the process of wearing it. Naroop said one of his earliest memories was taking his grandfather’s turban from the shelf, and dancing with it on his own head.

“My grandfather didn’t tell me off, but he took it off me and told me the turban was to be respected and was not a toy,” he recalled.

His grandfather explained that the turban was more than just a garment – symbolically, it had immense meaning. That message stuck with Naroop.

“Whenever I saw a man with a turban, I would always think I needed to respect him,” he said. “That was my own understanding and it came from respect for my grandfather and others who wore turbans.

“To this day, anyone who wears a turban, I show them respect because it isn’t easy to stay true to an identity that isn’t the norm.”

For more, see here: https://www.amitandnaroop.com/turbansandtales/