AMERICAN ARTIST WALKER ‘DOES NOT SHY AWAY FROM COMPLEX HISTORIES’

by AMIT ROY

THE American artist has taken the idea of the joyous Victoria Memorial in front of Buckingham Palace and subverted it to create Fons Americanus, by way of a scathing critique of the slave trade in which America and Britain were implicated.

The sculpture, a 42ft tall fountain in the Turbine Hall of Tate Modern, incorporates a noose hanging from a branch, sharks in the water and a distressed boy filling a shell with his tears to denote the African experience of the slave trade.

This is not an exhibition that will go down well with right-wing English historians, who insist that colonial Britain might have had a few flaws, but brought a civilising influence on the whole to lesser mortals. Possibly, after Brexit, some of them say, the glory days will return.

Could Walker’s work be connected to the Windrush scandal and the “hostile environment” for immigrants witnessed during Theresa May’s tenure at the Home Office?

The response was a careful but honest one from Dr Achim Borchardt-Hume, head of exhibitions at Tate Modern. He said the Turbine Hall and Tate Modern were used “to have debates about the society we live in, the society we want to live in ... of course, there is a relationship thinking about where are we today in the context of post-colonialist history”.

Describing Walker as an “extraordinary artist”, Tate Modern’s director Frances Morris said: “The Turbine Hall occupies a unique place in the public imagination. It has acted as a stage for cutting-edge, risk-taking contemporary art.”

She encouraged people to examine public sculptures in Britain’s towns and cities with a new understanding after visiting Walker’s latest work, part of a series commissioned by South Korea’s Hyundai Motor Company.

Morris implied that sculptures which celebrated colonial achievements often hid a darker truth. Walker, she added, was “the first artist to respond to the role of civic sculptor in our towns and cities, bringing her own rereading of London’s vast Victoria Memorial”.

Clara Kim, the exhibition’s senior curator in international art (Africa, Asia & Middle East), commented: “Kara’s investigations of race and gender and sexuality and violence is something that resulted in a profound group of works in the way she brings in fact, fiction and fantasy, (which) come together in very compelling ways. Her work deals with complex histories and doesn’t shy away from it and there are no easy answers.”

Could an artist have taken the statue of Queen Victoria in front of the Victoria Memorial Hall in Kolkata, for example, and produced a similar critique of the British Raj in India?

The reply from Priyesh Mistry, assistant curator (international art), certainly wasn’t kneejerk: “The history of colonialism is very complex – we wouldn’t be here otherwise. I am Gujarati, my parents came from Kenya.”

Mistry later explained the historical and contemporary references incorporated by Walker in her monumental work.

“There are disaster scenes and threat from sharks and the dangers of that kind of journey across the Atlantic,” he said. “Contemporary references include Turner and Damian Hirst’s Shark.”

Mistry was referring to JMW Turner’s Slave Ship 1840, Winslow Homer’s Gulf Stream 1899 and Hirst’s tiger shark, The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living 1991, which featured the creature suspended in formaldehyde.

Walker had also used the imagery and poetry of William Blake, currently the subject of a major exhibition at Tate Britain.

Mistry said: “There is a scallop shell as you enter the Turbine Hall which comes from depictions of Venus, including (that by) Botticelli. In Venus’s place you have a figure of a crying boy in this well, this pit, which references Bunce Island in Sierra Leone, a colonial commercial port where enslaved slaves were traded and forced on to the ships before they made that treacherous journey across the Atlantic.”

The “captain” was a composite figure of various people who had “led rebellions against colonial powers which had oppressed the African diaspora”.

“There is a direct reference to Queen Victoria at the back of this object – she stands there in joy and celebration in a way and full of life,” Mistry continued. “However, under her skirt there is figure of melancholy, kind of half hiding, which could be Queen Victoria’s own persona masked by all that good cheer.

“Finally, we have Venus herself on top of the fountain, a priestess from Afro Caribbean-Brazilian religion with water springing from her blessing the world

Tate Modern points out that “the full title of the work is... written in Walker’s own words.

...She presents the artwork as a ‘gift … to the heart of an Empire that redirected the fates of the world’. She has signed the work ‘Kara Walker, NTY’, or ‘not Titled Yet’, in a play on British honours awards such as OBE (Order of the British Empire)”.

- Kara Walker: Fons Americanus is at the Turbine Hall, Tate Modern until April 5, 2020.

'The Guilt Pill' her latest booksaumyadave.com

'The Guilt Pill' her latest booksaumyadave.com

Milli Bhatia

Milli Bhatia

Prithviraj Kapoor and Ramsarni Mehra Reddit/ BollyBlindsNGossip

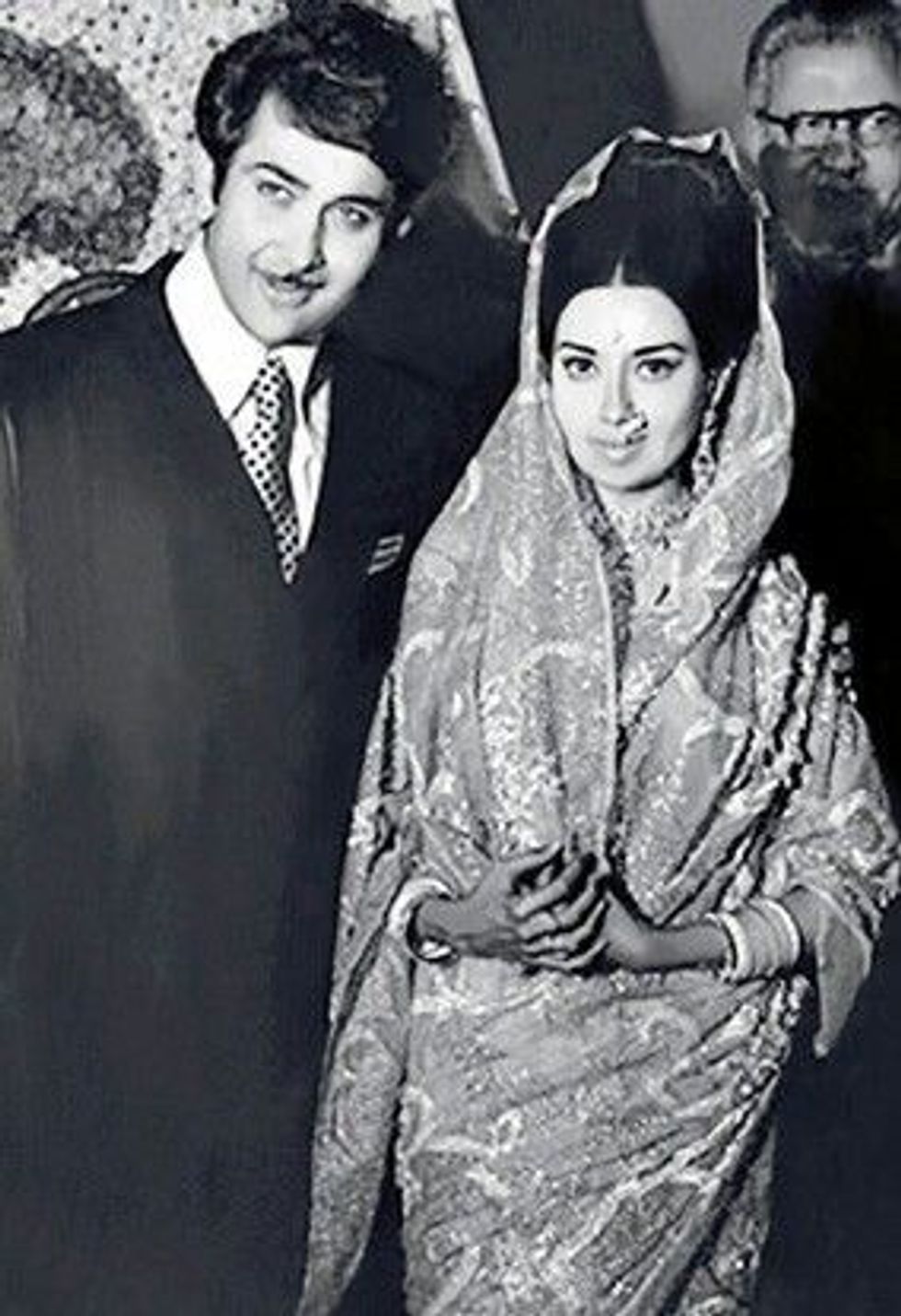

Prithviraj Kapoor and Ramsarni Mehra Reddit/ BollyBlindsNGossip Raj Kapoor and Krishna MalhotraABP

Raj Kapoor and Krishna MalhotraABP Geeta Bali and Shammi Kapoorapnaorg.com

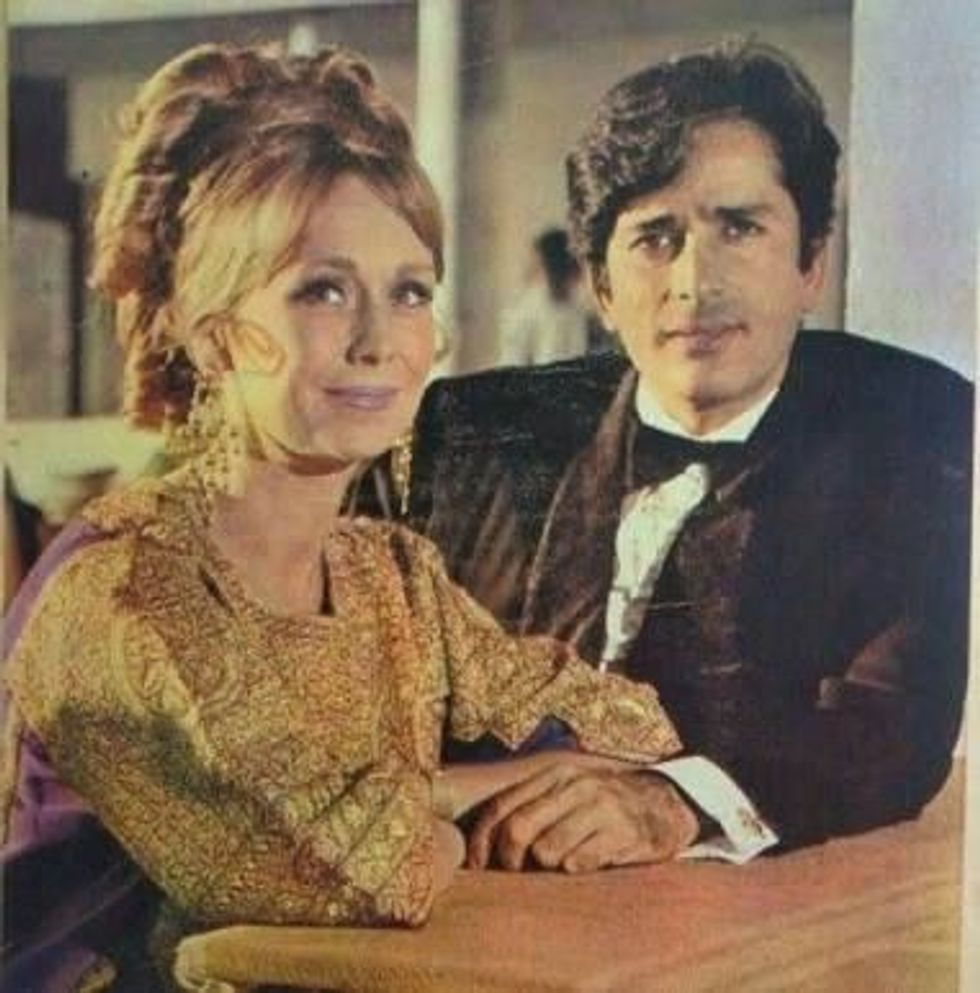

Geeta Bali and Shammi Kapoorapnaorg.com Jennifer Kendal and Shashi KapoorBollywoodShaadis

Jennifer Kendal and Shashi KapoorBollywoodShaadis Randhir Kapoor and Babita BollywoodShaadis

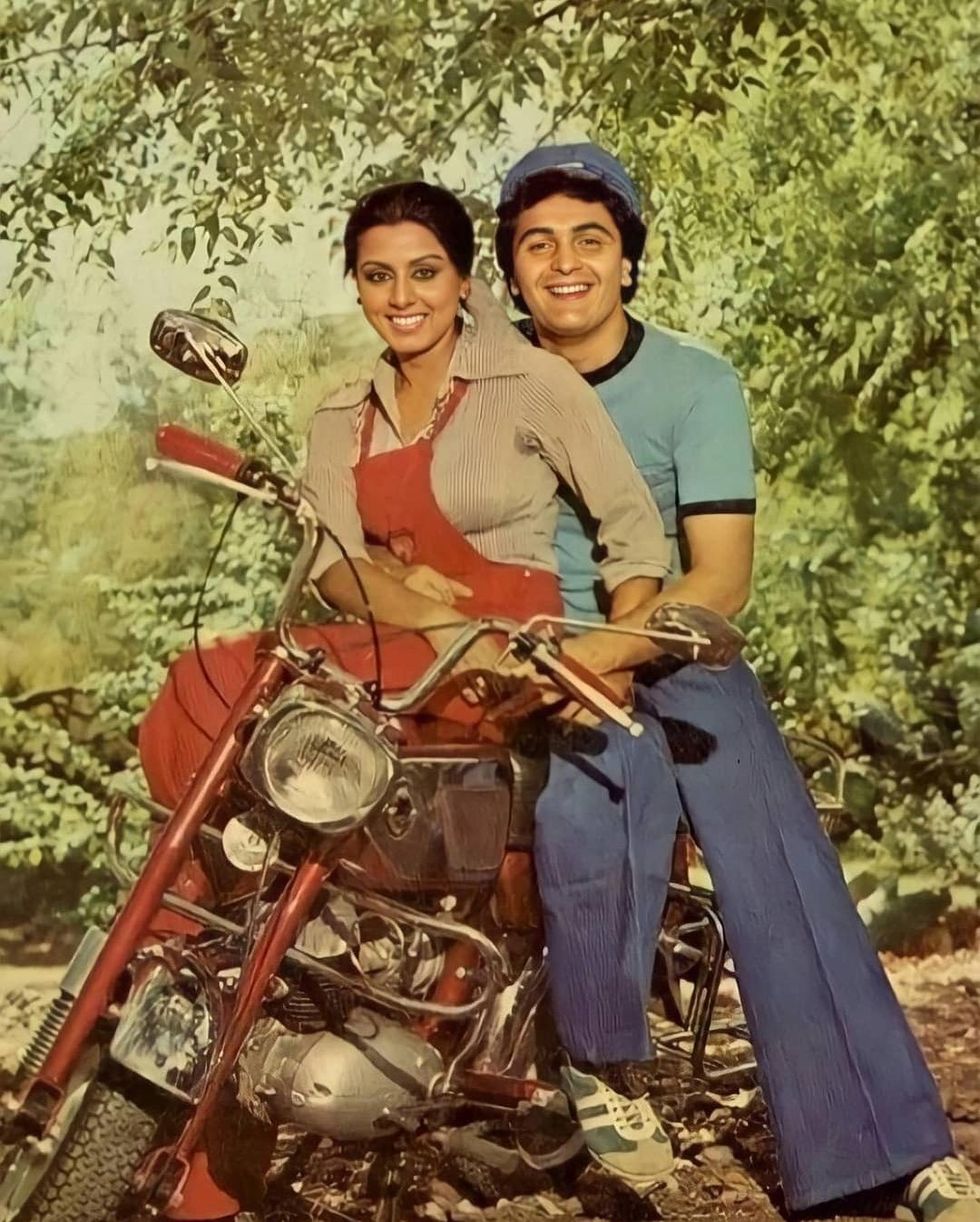

Randhir Kapoor and Babita BollywoodShaadis Neetu Singh and Rishi KapoorNews18

Neetu Singh and Rishi KapoorNews18 Rajiv Kapoor and Aarti Sabharwal Times Now Navbharat

Rajiv Kapoor and Aarti Sabharwal Times Now Navbharat Alia Bhatt and Ranbir KapooInstagram/ aliaabhatt

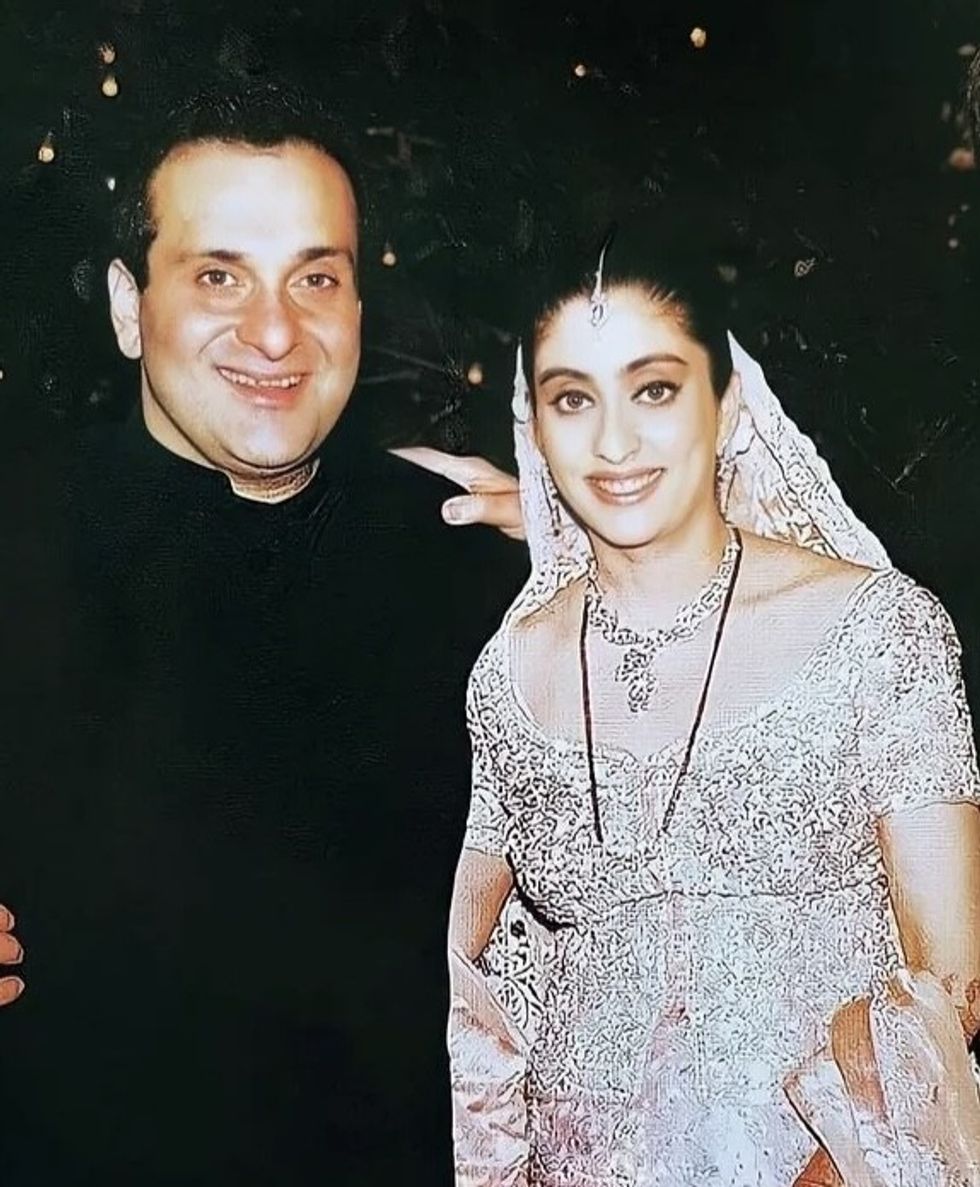

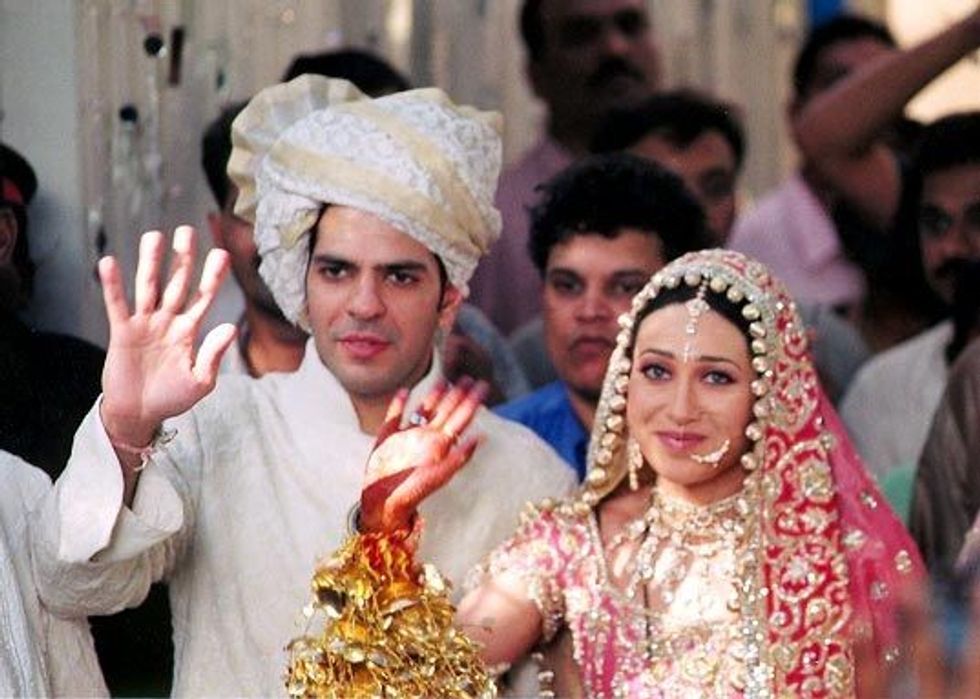

Alia Bhatt and Ranbir KapooInstagram/ aliaabhatt Sunjay Kapur and Karisma KapoorMoney Control

Sunjay Kapur and Karisma KapoorMoney Control

With actor Kanwar Dhillon in 'Ram Bhavan'Instagram/ rahultewary

With actor Kanwar Dhillon in 'Ram Bhavan'Instagram/ rahultewary Udne Ki AashaScreen Grab 'Udne Ki Aasha'

Udne Ki AashaScreen Grab 'Udne Ki Aasha'