The immigration white paper has been delayed to after the May local elections. The delay is sensible, as US president Donald Trump’s tariff games make economic conditions less predictable than ever, but necessary too. UK government ministers know how they want to talk about immigration – that control matters – but are torn about what policies that leads to.

There are real dilemmas of control. Downing Street and the Home Office want overall numbers to come down, but chafe at the Treasury constraint of making the fiscal numbers still add up. Health secretary Wes Streeting wants to invest more in NHS training, but not to turn away doctors and nurses who could reduce waiting lists in the meantime. With university finances more fragile than ever, education secretary Bridget Phillipson does not want to push half a dozen local universities over the brink to deliver a statistic on immigration.

Prime minister Sir Keir Starmer wants to “reset” the post-Brexit relationship with the EU at a summit this month – but can he agree on a youth mobility scheme for young people without reviving Brexit divides in Britain?

Delaying a little longer may help. The rear-view mirror drives immigration politics, looking back at the exceptional peak numbers of the last parliament. Net migration was 728,000 in the year before the general election – but immigration visa numbers fell sharply from 1.2 million to just under 800,000 since. The post-election rate of net migration is heading much closer to 300,000 than 700,000 – as the next rounds of headline figures in May and November will show. The Starmer government will be the first in living memory to exceed expectations on reducing immigration numbers, albeit mostly by sticking to the policies it inherited. But how far will anybody notice? Immigration salience reflects the visible lack of control of small boats and asylum hotels more than net migration statistics. The political debate will not shift unless government seeks to reframe it.

Falling immigration highlights a curious gap. This government’s policy is to reduce immigration – but with no public account of its preferred level or why. That mattered less given the common-sense consensus that inflows of up to 900,000 were unsustainable. Would this government keep saying that at 350,000 or 300,000? What about if it was 200,000 – with political opponents saying it should be net 100,000 or net zero? The past two decades show the limits of ‘pick a number’ sloganising about immigration levels if there is no serious mechanism in government or parliament to bring together the choices that decide them.

No other major democracy makes the net migration statistic so central to politics as Britain does. Home secretary Yvette Cooper and chancellor Rachel Reeves have criticised net migration targets for many years. The measure does not differentiate between different flows. Cooper often emphasises the futility of governments setting targets they always missed – but that does not quite answer the question of whether this government thinks net migration is a metric that does or does not matter.

Overall inflows to the settled population do make a difference to housing demand. Net migration running at over one per cent of the population (685,500) is unsustainable; yet the peak rate rose as high as 1.5 per cent under the Conservatives. The previous peak had been an inflow of 0.5 per cent of the population in 2016. This government could realistically treat that as a future ceiling for policy planning. Politicians – in government or opposition – who want to reduce numbers below that level need serious answers about the social care and NHS workforce and how to fund universities. They will also need to account for the hole in the public finances if governments reduce income from international students, visa fees and the NHS surcharge.

In such volatile times, declaring the right level of migration in four years’ time is impossible. A successful white paper should set out the framework for more accountable future decision-making. There is an emerging new consensus about this among policy wonks. A new Institute for Government proposal for an immigration plan – analogous to the three-year spending review and annual Treasury budget – reflects a new consensus on process from IPPR and Labour Together on the centre-left, Onward and the Centre for Policy Studies from the right, as well as non-partisan expertise from British Future and the Institute for Government itself. Politicians can see the merits too. Robert Jenrick backed the idea after he resigned from the previous Conservative government. Cooper supported this proposal when she chaired the Home Affairs Select Committee. The question is which politicians will support greater accountability when they are in power, not just in opposition. This government has an interest in producing a white paper that could reframe how we talk about the pressures and gains of immigration. An Immigration Plan could be the practical means it needs to move the argument on.

The Calcutta Club

The Calcutta Club The Bengal Club lawns

The Bengal Club lawns

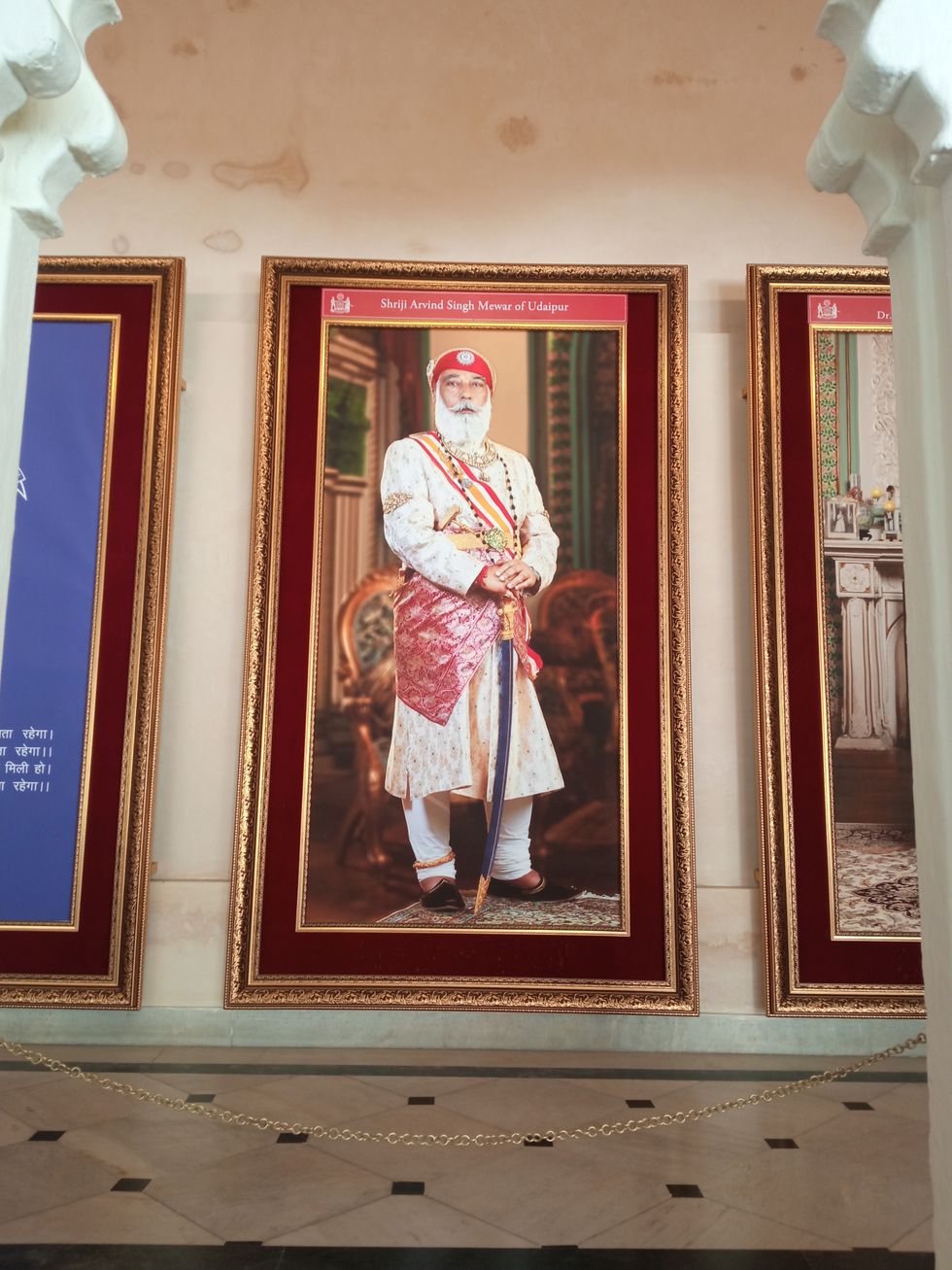

His portrait in the City Palace

His portrait in the City Palace

Pakistani artist Moazzam Ali Khan caught the attention of Bollywood legend Javed Akhtar with his soulful YouTube cover of Yeh Nain Deray Deray

Pakistani artist Moazzam Ali Khan caught the attention of Bollywood legend Javed Akhtar with his soulful YouTube cover of Yeh Nain Deray Deray John Abraham to headline action thriller Tehran

Getty Images for DIFF

John Abraham to headline action thriller Tehran

Getty Images for DIFF

Tikri Border, Haryana-Delhi by Aban Raza

Tikri Border, Haryana-Delhi by Aban Raza Harmz Matharu

Harmz Matharu Abhishek Bachchan in Be Happy

Abhishek Bachchan in Be Happy Devika's soulful vocals shine in her new Punjabi ballad Wisteria

Devika's soulful vocals shine in her new Punjabi ballad Wisteria Indian Idol star Nitin Kumar promises a soulful mix of qawwali, Sufi, and folk music at his upcoming UK performance

Indian Idol star Nitin Kumar promises a soulful mix of qawwali, Sufi, and folk music at his upcoming UK performance Kunal Kamra during his show

Wikipedia

Kunal Kamra during his show

Wikipedia

Swiss-Indian singer BombayMami is making waves with her bold style and sound

Swiss-Indian singer BombayMami is making waves with her bold style and sound Hania Aamir receives a questionable honour in London

Hania Aamir receives a questionable honour in London

A resident in Odessa, Ukraine, as smoke rises from a fire following a strike earlier this month amid the Russian invasion

A resident in Odessa, Ukraine, as smoke rises from a fire following a strike earlier this month amid the Russian invasion