In the UK, local governments have declared a Climate Emergency, but I struggle to see any tangible changes made to address it. Our daily routines remain unchanged, with roads and shops as crowded as ever, and life carrying on as normal with running water and continuous power in our homes. All comforts remain at our fingertips, and more are continually added. If anything, the increasing abundance of comfort is dulling our lives by disconnecting us from nature and meaningful living.

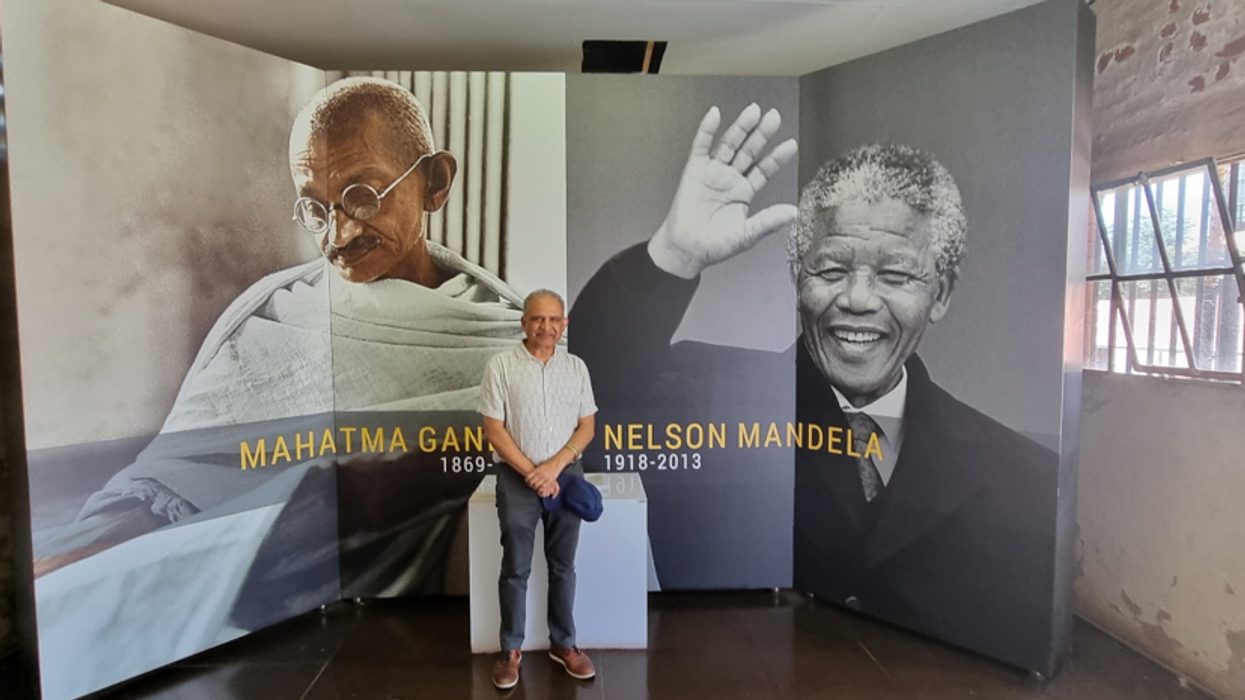

I have just spent a month in South Africa, visiting places where Mahatma Gandhi and Nelson Mandela lived, including the jails. They both fought against the Apartheid laws imposed by the white ruling community. However, no oppressor ever grants freedom to the oppressed unless the latter rises to challenge the status quo. This was true in South Africa, just as it was in India. Mahatma Gandhi united the people of India to resist British rule for many years, but it was the threat posed by the Indian army, returning from the Second World War and inspired by the leadership of Subhas Chandra Bose, that ultimately won independence. In South Africa, the threat of violence led by Nelson Mandela officially ended Apartheid in April 1994, when Mandela was sworn in as the country’s first Black president.

Mahatma Gandhi was not a politician but a spiritual leader, and his teachings have stood the test of time. In this article, I focus on Gandhi’s advice regarding diet and non-violence. He advocated for a purely vegetarian diet devoid of animal products such as milk, cheese, or eggs—a diet we now call vegan. To lead a meaningful life or achieve spiritual progress, we should cease killing sentient beings that do us no harm simply to satisfy our palate, especially when plenty of other choices are available. There is an apartheid against sentient beings—who will rise to reduce their suffering?

Religious Impediments

Religious ideologies have shaped societal cultures and practices, some of which have included inhumane acts such as animal sacrifices, slavery, the caste system, and restrictive roles for women. Many of these practices are convenient and boastful acts of devotion that ignore basic animal rights and human values. Such cultural practices, consolidated by economic factors, often defy modern ethics.

There is a general reluctance to reinterpret religious texts in progressive ways, but only communities that adapt to contemporary needs will thrive in the long run—others will perish.

In Hindu philosophy, Krishna is closely associated with cows and is also called ‘Gopala,’ meaning protector of cows. For thousands of years, Indian culture, deeply rooted in Vedic philosophy, has distinguished between the worldly (Vyavaharika) view and the spiritual (Paramarthika) view. The spiritual view emphasizes humanity’s intrinsic connection with nature, all life forms, and the environment.

Around 10,000 years ago, our ancestors, including those in India, advanced agriculture using knowledge, tools, and animals such as cows, bulls, water buffaloes, and horses. Among domesticated animals, cows and bulls were most prominent. Rishis (sages) emphasized preventing cruelty toward cattle as a standard for protecting all animals. Associating cattle with Krishna served as a benchmark for others to follow.

In modern times, however, bulls are almost entirely absent from agriculture, while milk demand has surged, leading to excessive cruelty toward cattle. The table below shows the per capita consumption of meat and milk in 2022 in India, the UK, and the USA:

India’s high milk consumption and low beef consumption create economic imbalances, causing misery for farmers and cruelty toward animals. Bulls and calves, deemed unnecessary, are often killed shortly after birth. Cows that stop producing milk after four to five pregnancies lose their economic value and are sold for cheap meat. These cows endure extreme suffering during transport, often without food or water, tethered upright in overcrowded trucks for hundreds of miles.

Some self-proclaimed gurus advocate for gaushalas (cow shelters) by placing a few cows in them, but many of these initiatives are mere shows to raise money.

Poor farm-level economics has also led to unhygienic conditions for farmers, animals, and products like milk and meat. The dairy industry exploits packaging, social media, culture, and religion to promote milk products. India, where lactose intolerance is higher than in Western countries, also has the highest proportion of people suffering from diabetes and heart diseases.

India stands at a critical juncture—it can rise to heal itself, lead the world, and protect the planet.

Cognitive Dissonance

Cognitive dissonance occurs when a person’s behavior conflicts with their beliefs, values, or knowledge. Over the past 50 years, industrial (factory) farming has intensified, leveraging technological, scientific, and economic advancements to maximize productivity. However, this comes at the expense of severe animal cruelty, environmental degradation, and health risks.

For instance, chickens that stop laying eggs and cows that stop producing milk are slaughtered. Many cows on UK farms are so weakened by repeated births and poor diets that they can no longer stand. These “spent” animals are sold for cheap meat, often destined for fast food markets.

The negative impacts of industrial farming include:

- Ethical concerns: Animal cruelty (e.g., suffocating male chicks or slaughtering diseased animals).

- Environmental degradation: Greenhouse gas emissions and deforestation for animal feed.

- Health risks: Zoonotic diseases and antibiotic resistance.

Supply chains are designed to make animal products convenient and affordable, but they rely on consumer demand. Companies like Just Eat encourage mindless consumption, removing the effort and thought involved in food preparation. This disconnect shields consumers from unethical practices, harming both health and the environment.

Activists, educators, and charities in India, the UK, and the USA are working to reverse these trends.

Non-Violation of Dharma (Duty)

It is impossible to live a life entirely free of violence—walking on grass, gardening, or even vacuuming a house can inadvertently harm insects. Even plant-based diets involve some level of harm. However, a plant-based diet aligns with the principle of "least violence." This is why I prefer the term non-violation over non-violence.

Mahatma Gandhi, in his autobiography, states that humans need no milk beyond their mother’s milk and should sustain themselves on sun-dried fruits and nuts. Such a diet represents an ideal alignment of knowledge, thought, words, and actions—a hallmark of spirituality.

(Dr Prabodh Mistry (prabodh.mistry@gmail.com) qualified as a biochemical engineer, with a PhD from Imperial College London in 1985 and has a deep interest in applying human values in education, science and technology. He works as an environmental consultant, teaches mathematics and is a proponent of Sathya Sai Education in Human Values.)

Anurag Bajpayee's Gradiant: The water company tackling a global crisis