by LAUREN CODLING

DOCTORS have urged action to tackle “unjust” inequalities faced by BAME groups as new research found discrepancies in health-related outcomes between minorities and white Britons.

Those of Bangladeshi, Pakistani, Arab, and Gypsy or Irish Traveller backgrounds were considered to have a 20-year age difference in their health status, compared to those from equivalent white backgrounds, recent research published in The Lancet Public Health showed.

Ethnic groups were more likely to have underlying health conditions, poor experiences of primary care, insufficient support from local services and high area-level social deprivation, researchers found.

Responses were collected from patients registered at GP practices across England from July 2014 to April 2017, prior to the pandemic.

Researchers looked at how ethnicity was associated with five self-reported health issues – mobility, self-care, activity such as working or housework, pain or discomfort, and anxiety or depression. They then gave each patient a “health-related quality of life” for each ethnic group, ranging from perfect health (1) to poorest health (-5.94). The study found that on average, each of the five main ethnic groups scored poorer than white Britons, to the extent that it was as if patients from these groups were 20 years older than their counterparts.

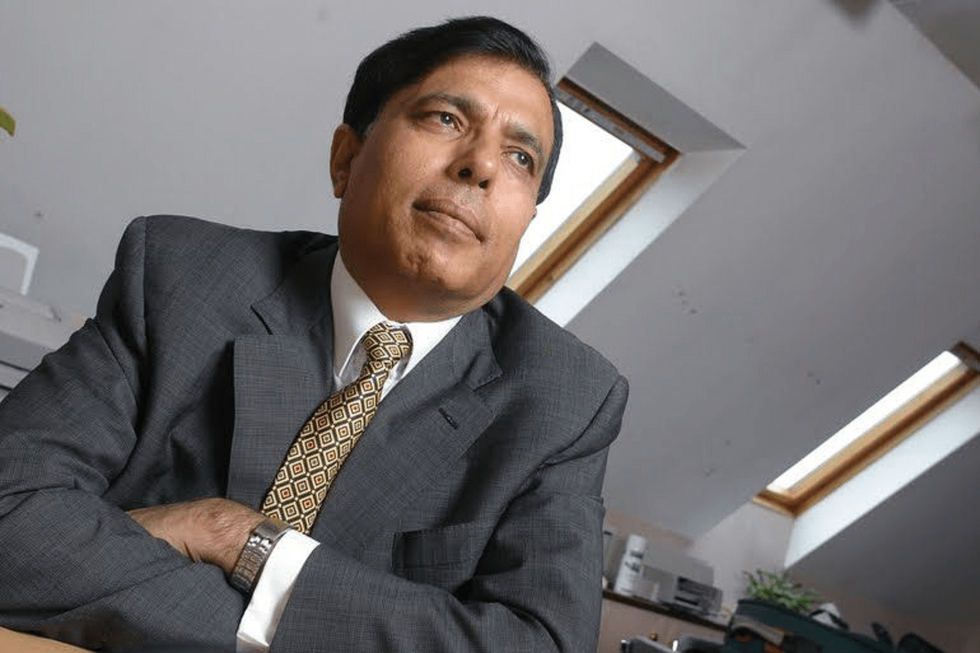

The British Medical Association (BMA) council chair, Dr Chaand Nagpaul, said the study highlighted the “enormous and unjust” health inequalities faced by minority ethnic groups in the UK. He warned the issues have prevailed for “far too long”.

The ongoing pandemic has further exacerbated the social, ethnic and economic divides within Britain, Dr Nagpaul added. Since the coronavirus outbreak last year, studies have consistently shown ethnic groups have been disproportionately impacted by the virus.

“Indeed, it would be short sighted not to see that health inequalities are partly to blame for the high Covid-19 death rates in this country,” Dr Nagpaul told Eastern Eye. “The dearth of public health provision reduces the life chances of already socially disadvantaged and clinically vulnerable groups – this must be urgently addressed.”

Dr Habib Naqvi is the director of the NHS Race and Health Observatory, an independent group working to tackle ethnic and racial inequalities in healthcare for patients, communities and the NHS workforce. Noting the findings, Dr Naqvi said the observatory was committed to closing the gaps in healthcare access and outcomes between ethnic groups.

“We know structural health inequalities blight the lives of many people from ethnic minority groups in disparaging and, often, life-limiting ways,” he told Eastern Eye. “It is therefore crucially important that we address the persistent and troubling problem of ethnic inequalities in relation to health.”

Dr Kailash Chand, the honorary vice-president for the BMA, told Eastern Eye any systematic investigation of any inequities in access to care has been “hampered by the failure of NHS institutions to collect ethnicity data on patients both at hospital and primary care level”.

“There is some evidence that the NHS has not catered well to Britain’s ‘diverse’ population,” he added. Dr Chand referred to a previous Department of Health patient survey which revealed a consistent pattern of higher levels of dissatisfaction with NHS services among some minority ethnic groups, when compared with the white majority.

“Those responding to the survey from BAME backgrounds reported significantly poorer experiences (as hospital inpatients) than white British or Irish respondents, particularly on questions of prompt access, as well as their experience of involvement and choice,” the Manchester-based GP said. He also noted BAME leadership at high levels is “very poor” – there are very few ethnic minorities involved in the delivery of the service that they use.

Dr Farzana Hussain, an NHS clinical director and GP, was also critical about the lack of senior ethnic minorities in the healthcare system, recommending an investigation into the cause of this. “More needs to be done to look into why people aren’t coming forward (for these roles),” she said. “Is it that they don’t feel confident or empowered enough?”

Dr Hussain’s GP surgery is based in Newham, east London. The borough has one of the highest BAME populations in the country, with an estimated 73 per cent of the population hailing from an ethnic background. She said there was a significant lack of investment in the area, with evidence showing Newham was the second poorest borough in England. The first is Tower Hamlets in east London, which also has a substantial BAME population.

She said there was a link between the findings and the lack of funding is areas such as Newham.

Both Dr Nagpaul and Dr Chand called for action, rather than more reviews and reports on inequalities. “We have known these problems have existed for decades, so further evidence-seeking exercises on ethnic disparities and inequalities while useful, should not deter the urgent action that is clearly needed,” Dr Nagpaul said. “The BMA believes that attention should now be on implementation of solutions to address the known ethnic disparities and inequalities, with any further research focused on where it is required to support or monitor action.”

Dr Chand added: “We have plenty of reports – we need action. Empty rhetoric makes no difference. A culture change in the long run and mandatory targets and penalties in the short term are essential.”

Ruth Watkinson, the lead author of the report, from the University of Manchester, said, “We need decisive policy action to improve equity of socio-economic opportunity and transformation of health and local services to ensure they meet the needs of the multi-ethnic English population.”

Co-author Alex Turner added the data showed the need for “more nuanced research” to understand the specific barriers to good health in older ethnic groups. “For example, Bangladeshi, Pakistani and Chinese ethnicities are often all categorised as ‘Asian’,” he said. “In our study, people of Bangladeshi and Pakistani ethnicity had the worst disadvantage in health, compared with white British, whereas people of Chinese ethnicity had a relative advantage.”

The analysis surveyed almost 1.4 million adults aged over 55, including more than 150,000 people who self-identified as belonging to an ethnic minority group