This week marks the first anniversary of the biggest human tragedy in the English Channel for decades.

On 24th November last year, a fishing boat spotted dozens of bodies floating in the icy water. A rubber dinghy had left the French coast the previous evening but capsized before reaching England.

At least 27 of the 34 people on board died, with five still missing, and just two survivors. Candelit gatherings on the beaches at Sunny Sands in Folkestone and across the water in Dunkirk in France mark Thursday’s anniversary, remembering how those who drowned are mourned as mothers and fathers, sons and daughters.

Harrowing details of their final hours emerged this month. The French newspaper Le Monde reported on how French authorities received distress calls at 1.51am, with the boat in French waters, but later told passengers seeking help at 2.30am and 3am as the dinghy capsized that they should call 999 instead as they had drifted into British waters. Logs of calls made to the British authorities have yet to be released. A UK Marine Accident Investigation will not report until next summer. Issa Mohammed, a Somali asylum seeker who survived, told ITV’s The Crossing documentary of hearing children screaming while those emergency calls were made, and how those who died in the freezing water held hands until the end.

That human tragedy shows why dangerous journeys across the Channel can be nobody’s idea of a well-managed system for claiming asylum. Yet hopes that so many deaths might lead to a less heated public argument proved short-lived.

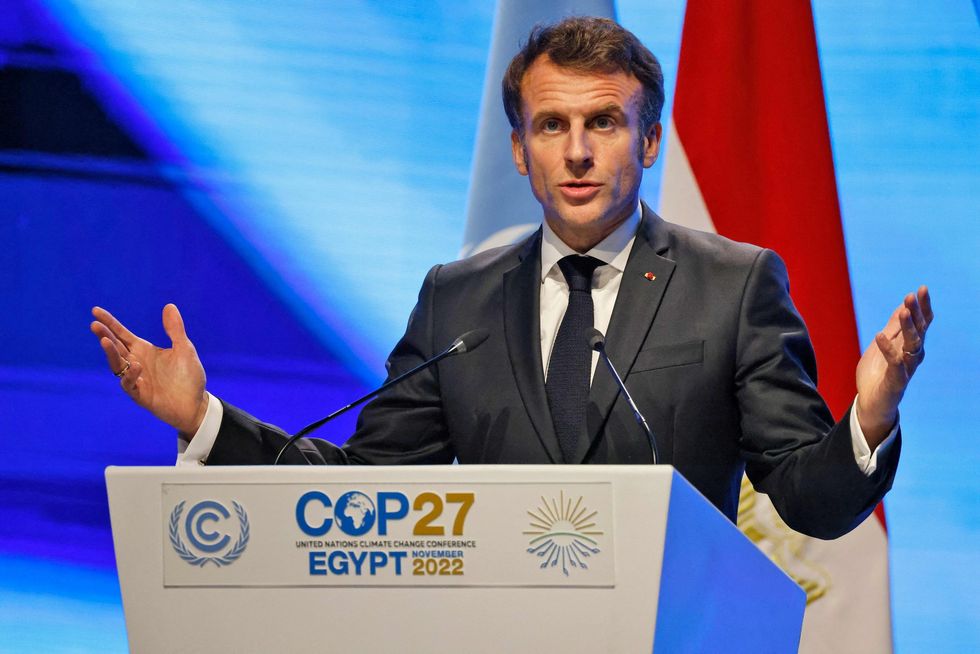

French President Macron did sombrely state that ‘we can not let the Channel become a graveyard’. Prime Minister Boris Johnson acknowledged that the tragedy was predictable and risked happening again. Yet within days, the British and French governments were clashing again. Ironically, Johnson’s letter to President Macron calling for closer inter-governmental cooperation led to Home Secretary Priti Patel being disinvited from a meeting with her European counterparts. The French complained that Johnson’s letter being posted on Twitter before being received in Paris made it less a serious diplomatic initiative than part of a political blame-game.

The current administration of British prime minister Rishi Sunak administration now seeks a more constructive relationship with France. The two governments have struck a new deal to try to contain the crossings. Yet both governments say that they have stopped more than 30,000 attempted journeys and that more boats are getting through. Over 40,000 people crossed the Channel over the past year.

The threat to life remains real. Over 6,000 people have been rescued at sea. NGOs in France report that many are just dumped back, disorientated, on the French coast, before trying to cross again. Those who make it to the UK via France are usually told, under last year’s new borders bill, that they can now be deemed inadmissible to claim asylum in the UK. Yet this usually just adds another delay of several months before around 99% are admitted into our asylum system anyway.

While the UK has no returns deal with France, it lacks any realistic legal alternative in many cases. A deeper deal with France would reach beyond enforcement, and also seek to negotiate a framework for who could claim asylum in the UK, and how, and who should not.

Instead, the government’s flagship policy was a deal with Rwanda to deport asylum seekers to Africa. The Sunak administration will try to defend its legality in the courts but with fading confidence that the plan would deter the crossings anyway.

Despite the £140 million paid to Rwanda, the policy is unlikely to be operational before the next election – and will probably never become operational at all. The growing asylum backlog could have been cleared months ago for a fraction of that spending. The Rwanda policy exemplifies an all-too reliable rule of asylum politics: the political theatre that generates most media headlines often has least practical impact on delivering a functioning asylum system.

The hard work to do that can challenge all sides. Those who see border control as the litmus test of post-Brexit sovereignty cannot deliver this in reality without negotiating with other sovereign states. Governments who want migration via legal routes will struggle to make trafficking unviable while those routes do not exist.

Those who died a year ago came from eight different countries - Afghanistan and Egypt, Eritrea and Ethiopia, Iran and Iraq, Somalia and Vietnam - where even people with UK ties rarely have any safer route to seek asylum here. Those outside government, pressing for such safe routes, also need credible answers on practical challenges – such as what should happen to those whose asylum claims fail.

The anniversary of the Channel tragedy should remind us all why our urgent need for a more orderly, more effective and more humane system of asylum can be a matter of life and death.

Doraiswami addresses guests at the event

Doraiswami addresses guests at the event

Liakat Hasham and other dignitaries receive Aga Khan in the UK during an official visit

Liakat Hasham and other dignitaries receive Aga Khan in the UK during an official visit

Why Britain needs a more humane asylum system

On the first anniversary of the Channel tragedy, UK must relook its policy