THE latest research shows a majority of people – 64 per cent – are still “proud” or “very proud” of Britain’s history, but the figure has dropped from 86 per cent in 2013.

The findings in the British Social Attitudes Survey 2023 are based on a poll of 4,611 people done in April this year by YouGov.

It found that 81 per cent of those aged 65 or above were “very” or “fairly” patriotic, compared to just 39 per cent of 18 to 24-year-olds and 45 per cent of those aged between 25 and 49.

Alex Scholes, the senior researcher at the National Centre for Social Research (NatCen), which conducted the survey, said there was a connection between changing attitudes and the fact that there are fewer people alive today who lived through or fought in the Second World War.

“It definitely has an impact,” Scholes said. “History is possibly the standout area, because that’s where we’ve seen the greatest drop over the past decade. It was consistently over 80 per cent between 1995 and 2013 and now it’s 64 per cent, and that’s quite a sizeable drop in the last decade.”

Gillian Prior, deputy chief executive of NatCen, said the survey shows Britain is a “nation redefining itself”.

“These research findings show that while we are less likely to take pride in British history and [are] more critical about its politics, there is still a great deal of national pride in the country’s cultural and sporting achievements,” she said.

Prior added: “This change in attitudes may have been influenced by the increased diversity and shared citizenship within Britain, presenting a portrait of a nation redefining itself.”

To me the sample looks very small, but nevertheless, some historians have tried to put a spin on the findings.

Robert Tombs, professor emeritus of French history at Cambridge, said increasing criticism of slavery and the British empire has also contributed to the decline in pride in the country’s history. “I expect that not only the passing of the generation who lived through the war, but also of those who knew people who lived through the war is significant,” Tombs said.

“But the generally negative portrayal of British history in the media, fiction, TV, films and schools must surely have had an effect. This is true across the Anglophone world.”

Professor Lawrence Goldman, of St Peter’s College, Oxford, said: “Too much history teaching seems to start now from an assumption that the empire was inevitably malign.

“I would suggest that it’s not just about the distance now between events in 1914 and 1939, and the death of all the combatants, though, of course, these are factors.

“We are failing to explain why those wars had to be fought, what sacrifices they entailed and how everyone across the world, of all races and backgrounds, ultimately benefited from the defeat of militarism and dictatorship.

“We have lost that sense of what was at stake, with a consequent decline of pride in the sacrifices endured.”

There is another way to interpret the figures. Britain is an open society where people are proud of their culture and traditions, but are not afraid to be critical of the country’s past involvement in the slave trade or the evil aspects of empire.

As a child in India, we grew up with the romantic image of England as the land of Shakespeare, Keats and Shelley – and, despite everything, that perception has stayed with me down the years.

Priya Malik

Priya Malik Kaavish

Kaavish Kesari: Chapter 2

Kesari: Chapter 2 Laapataa Ladies

Laapataa Ladies Rizwan Muazzam

Rizwan Muazzam Manasi Ghosh

Manasi Ghosh Kavya Limaye

Kavya Limaye L2: Empuraan

L2: Empuraan Rahat Fateh Ali Khan

Rahat Fateh Ali Khan

The Calcutta Club

The Calcutta Club The Bengal Club lawns

The Bengal Club lawns

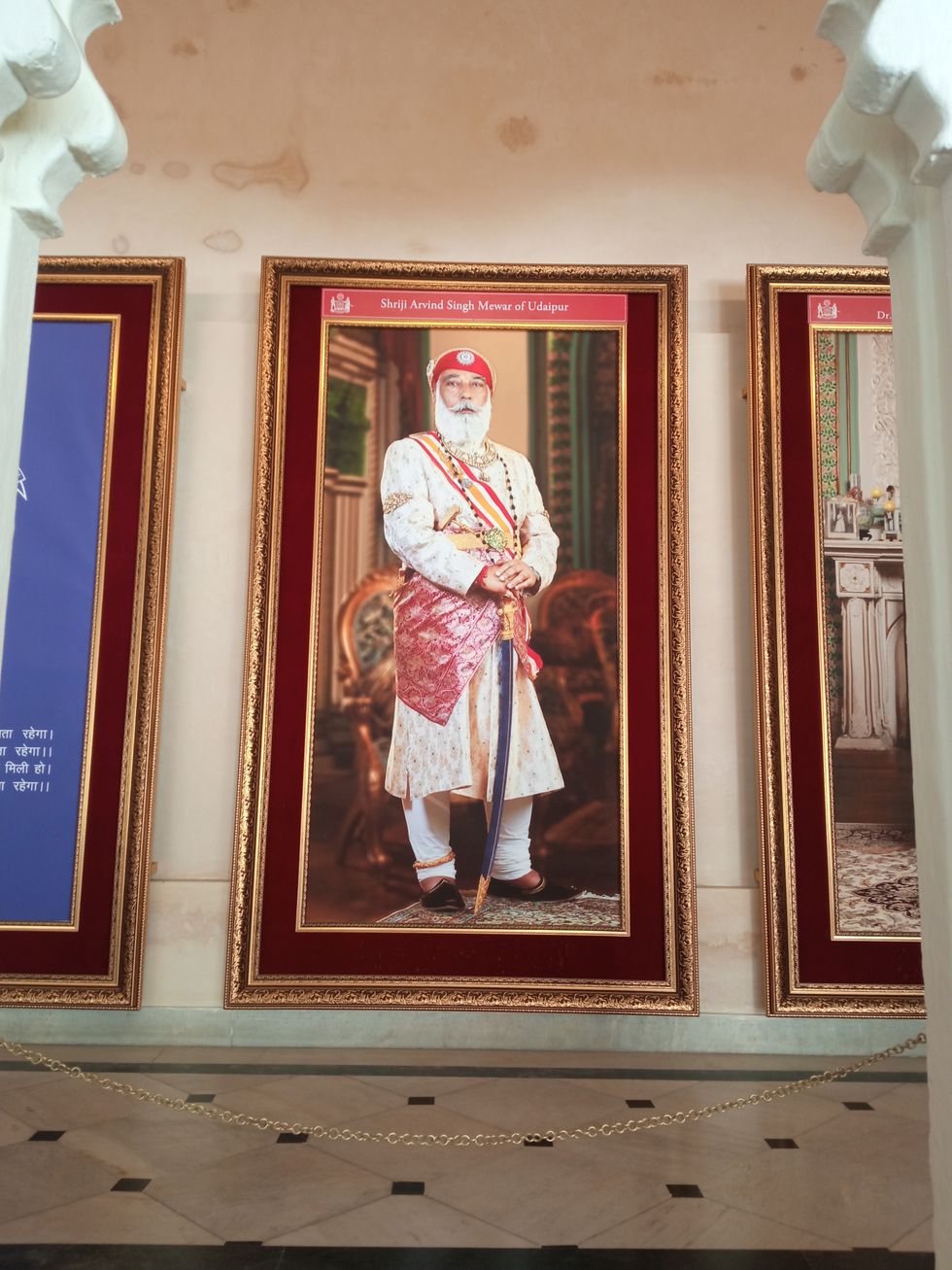

His portrait in the City Palace

His portrait in the City Palace

Pakistani artist Moazzam Ali Khan caught the attention of Bollywood legend Javed Akhtar with his soulful YouTube cover of Yeh Nain Deray Deray

Pakistani artist Moazzam Ali Khan caught the attention of Bollywood legend Javed Akhtar with his soulful YouTube cover of Yeh Nain Deray Deray John Abraham to headline action thriller Tehran

Getty Images for DIFF

John Abraham to headline action thriller Tehran

Getty Images for DIFF

Tikri Border, Haryana-Delhi by Aban Raza

Tikri Border, Haryana-Delhi by Aban Raza Harmz Matharu

Harmz Matharu Abhishek Bachchan in Be Happy

Abhishek Bachchan in Be Happy Devika's soulful vocals shine in her new Punjabi ballad Wisteria

Devika's soulful vocals shine in her new Punjabi ballad Wisteria Indian Idol star Nitin Kumar promises a soulful mix of qawwali, Sufi, and folk music at his upcoming UK performance

Indian Idol star Nitin Kumar promises a soulful mix of qawwali, Sufi, and folk music at his upcoming UK performance Kunal Kamra during his show

Wikipedia

Kunal Kamra during his show

Wikipedia

Swiss-Indian singer BombayMami is making waves with her bold style and sound

Swiss-Indian singer BombayMami is making waves with her bold style and sound Hania Aamir receives a questionable honour in London

Hania Aamir receives a questionable honour in London