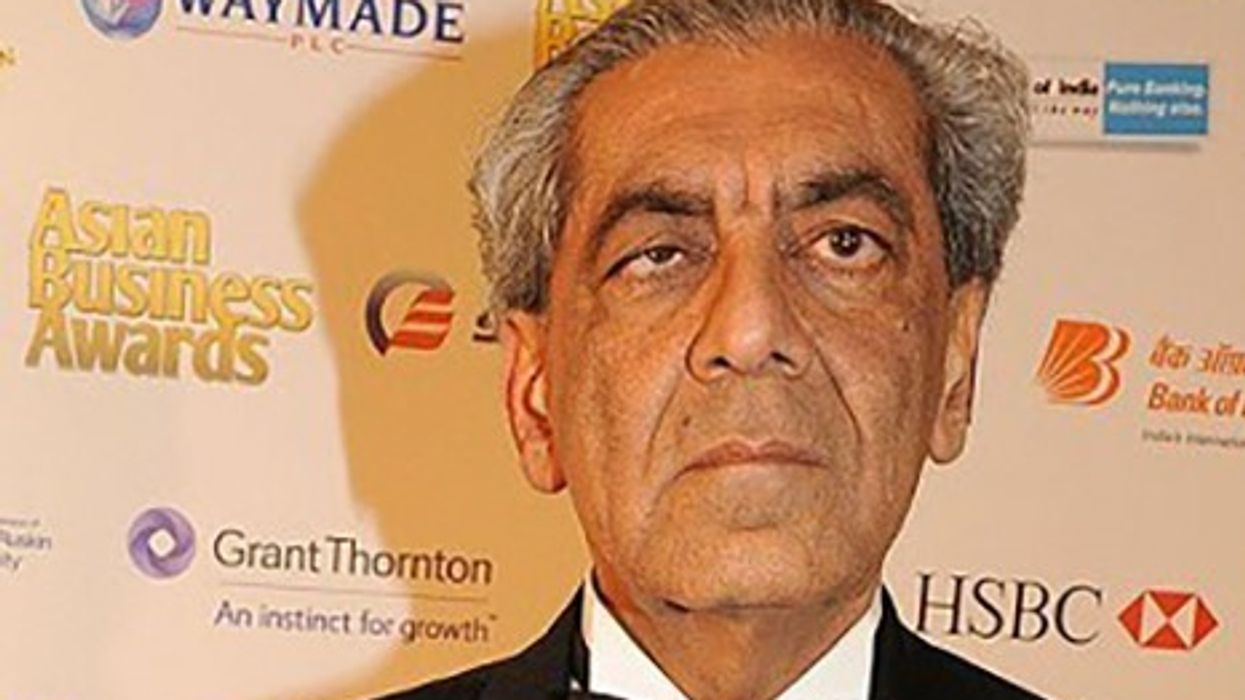

By Sailesh Mehta

IT IS in the nature of all governments, whether democratically elected or autocratic, to amass more and more power until their citizens say “enough”.

Ministers of state do not like protesters. Bad ones crush all dissent; good ones allow just enough steam to escape before the whole thing explodes.

The police, crimes, sentencing and courts bill seeks to give the home secretary and the police more powers to ban, curtail and crush protests. If a demonstration is deemed too noisy or too annoying, the police will be able to restrict it. Parts of the bill create new powers of stop and search, as well as trespass provisions that may lead to increased police enforcement against minority communities. It gives the home secretary power to legislate by decree, without the usual parliamentary scrutiny.

The second reading of the bill was voted through by a huge Tory majority last week and is likely to become law after a pause, when recent memories of violent arrests of female protesters at the Sarah Everard vigils have faded.

The home secretary has made no secret of her disdain for protesters. Her tough stance on law and order plays well to the Conservative party base and to the media that supports it. It begs the question how she might have reacted to historic protest movements that changed the course of human liberty for the better.

In March 1930, when Mahatma Gandhi started his salt march, it was a non-violent protest against the British Raj’s salt laws. Thousands of Indians joined him along the 240-mile route. This simple act of dissent led to widespread civil disobedience and the imprisonment of 60,000 protesters, including Gandhi. These were unlawful demonstrations against unjust laws and Gandhi’s actions were deemed to be seditious. Would our home secretary have allowed these peaceful marches if they were being organised today, or would she have sent in the police to stop the protests? Existing powers and the new bill would have allowed the police to ban all independence demonstrations and arrest every participant, particularly its leaders.

In December 1955, Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her seat on a bus for a white person. This incident sparked nation-wide protests led by Martin Luther King Jr. The violence inflicted on thousands of peaceful protesters horrified the world, filled up every prison and eventually led to changes in US segregation law. Would Priti Patel have sent in baton-wielding officers and vicious dogs to break up these unlawful but justified protests, or would she have exercised restraint and chosen not to use the new powers under the crime bill?

Patel’s immigrant parents came to the UK as refugees, being given shelter from Idi Amin’s murderous regime. As an MP, she has backed key parts of Theresa May’s ‘hostile environment’ policy for immigrants, leading to a stricter asylum system and to members of the Windrush generation being wrongfully told they had no lawful right to live and work in the UK.

In their fight for women’s voting rights, the Suffragettes regularly broke the law to raise awareness for their cause. Politicians and right-wing newspapers called for the police to crush their cause, of which Princess Sophia Duleep Singh and Emily Pankhurst were leading figures. A commentator said during the November 1910 ‘Black Friday’ protest : “I saw a policeman grab women by the collars, shake them and fling them aside like rats.” Would the police today have behaved in a similar heavy-handed way towards peaceful female demonstrators? Would the home secretary have supported such police violence if the Suffragette movement was happening today?

We will never know whether Patel encouraged the Metropolitan Police commissioner to go in hard against the peaceful vigil organised in memory of Sarah Everard, who was kidnapped and killed when walking home at 9.30pm on March 3. What we do know is that a message was sent to all police chiefs making Patel’s position clear – she wanted them to stop people gathering at vigils. She also promised she would personally urge people not to gather, a promise she broke.

The death of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in May 2020 sparked protests against the brutal treatment of black people in America by the police. Mass demonstrations, often declared unlawful, spread to every major city in the US and across the world. They led to much soul-searching, discussion and changes in legislation. The Black Lives Matter protests that swept the UK were described by our home secretary as “dreadful”, stating for good measure that she did not agree with the silent and peaceful gesture of ‘taking the knee’.

An index of the freedoms we enjoy is the extent to which legitimate protest is tolerated by the state. The extent to which we tolerate injustice without protest is the exact measure of legislative control that will be imposed upon us.

Dissent and protest are a healthy safety valve for every democracy. The more the home secretary clamps down on legitimate protest, the weaker she makes our democracy.

Sailesh Mehta is a barrister practising in human rights law.

Birmingham’s basic services are collapsing as council mismanagement leaves city flooded and filthy West Midlands Fire Service

Birmingham’s basic services are collapsing as council mismanagement leaves city flooded and filthy West Midlands Fire Service

Why the right to protest is vital in a democracy