IN WILLIAM DALRYMPLE’S new book, The Golden Road: How Ancient India Transformed the World, the historian has vividly set out how India, not China, “was the beating heart of Asia between 250 BC and 1,300 AD”.

He spoke about his findings, first in a lecture at the Financial Times Weekend Festival, and then in an interview with Eastern Eye.

The book, he said, is divided into three parts.

“The first part is the story of how Buddhism was exported, initially by Ashoka, but then subsequently by merchants and individuals without any state assistance, in all directions.

“It was initially to Sri Lanka, with Mahinda, the son of Ashoka, eastwards to the Mekong Delta, China, Korea and ultimately Japan; westwards to Egypt, where more and more Buddhist remains are turning up on the Red Sea,” he told Eastern Eye.

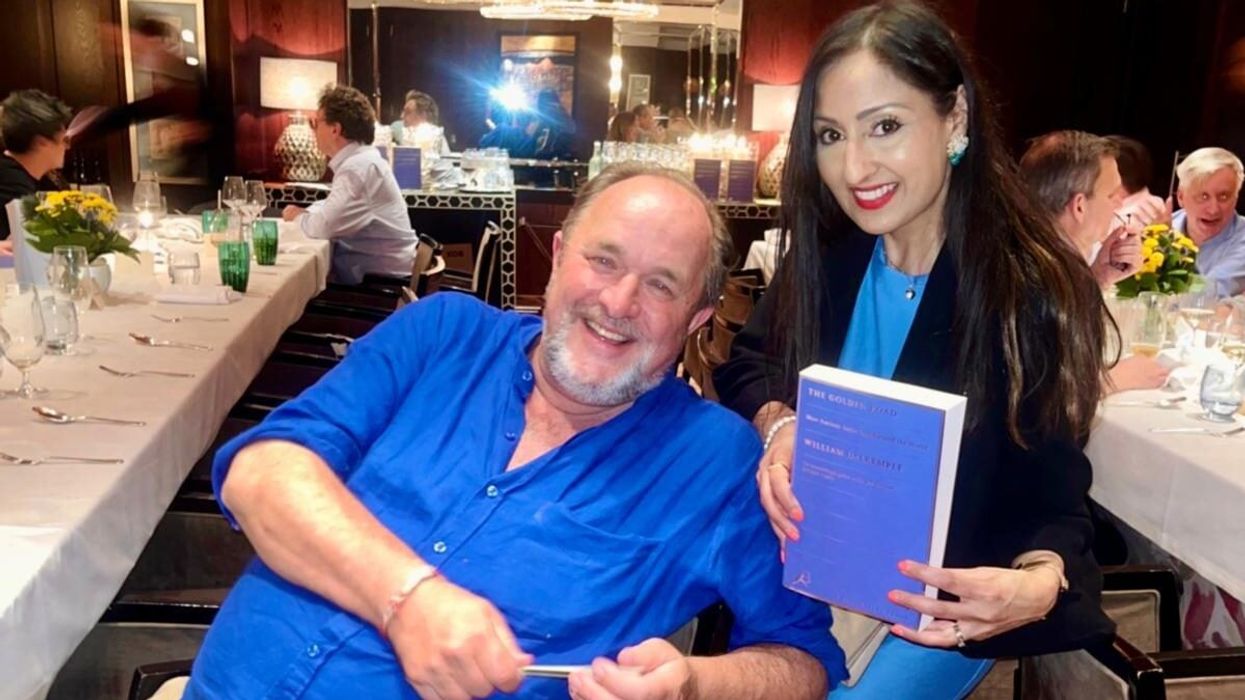

The cover of The Golden Road“And the book, in particular, is aimed as the corrective to this notion that China was the main organ of east-west contact, and the Silk Road, which sort of bypassed India in the classic map which went way to the north, was at all a thing until the 13th century. I think that the Silk Road existed, but only from the 13th century onwards.

“Up to that point, India was the centre of Asia and the monsoon winds blew Indian traders, missionaries, merchants, intellectuals, sages, mathematicians, westwards to the Arab world and the Mediterranean; eastwards to China.

“Part one is the story of the spread of Buddhism.

“Part two is how Hinduism and Sanskrit and the world of Sanskrit and Hinduism and Hindu kingship came to dominate Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, Malaysia and Vietnam.

“And the third part is how Indian numerals travelled west, first to the Arab world and then to Europe, with the Sanskrit literate former Buddhists who became the viziers in Baghdad. And they were the mediators who brought Indian mathematics and astronomy to the Arab world.

“It spreads through the translations and the transliterations of al-Khwarizmi, from whom the word algorithm derives. And then he’s read in Algeria by Fibonacci, who brings it into Italy. From Italy, it spreads through the rest of Europe.”

Dalrymple explained what he had done in The Golden Road: “So it’s a long relay lace of Indian influence, different ideas in different directions, but bringing them all together into a single narrative.

“So often, the story of the spread of Sanskrit is seen as something on its own, different from the spread of Buddhism, which is different from the spread of numbers.” He emphasised: “I think it’s all part of one process by which India is the beating heart of Asia, and that the Golden Road following the sea lanes using the monsoon winds, not some spurious Silk Road which never existed, is the force which knits it all together.”

That India was at the centre during this period “is not at all known in the west. Everyone knows it in India. On the current book tour (in the UK), I’ve been asking, how many know what they call Arabic numbers originated in India, and two people out of 1,000 will put up their hands – and they’re always Indian. It’s completely unknown here (in the west).

He had referred “totally tongue in cheek” to claims by some in India that there had been nuclear power in the past and people flying around.

“But this is, I think, out of the frustration that Indians have that no one in the west knows about their glorious past. This often assumes strange incarnations. And you do find, often on the internet, people talking about nuclear weapons in Kurukshetra and or plastic surgery in early India.

“And one of the jobs this book is trying to do is parse fact from fiction.”

He talked about the genesis of The Golden Road: “When I was growing up, I was always interested in archaeology. I got into university doing archaeology, and then ended up doing history and art history. So the two have come together. In my teens, I was digging on archaeological sites.

The temples sparked a curiosity about Indian cultural exports in the author“And when I first went to India, the places I was going to were Ajanta, Ellora, Sanchi and the ancient sites. I think my teenage self would be very surprised to learn that I spent most of my professional life writing about the 18th century.

“The idea came when I was visiting Angkor Wat. I was very surprised to see representations of Kurukshetra and the Battle of Lanka sitting in the middle of the Cambodia, stories which originated in northern India represented so far from home.”

He started working on The Golden Road after his last book, The Anarchy: The Relentless Rise of the East India Company, was published in 2019.

In his FT Weekend lecture, Dalrymple began by showing a picture of a Buddha’s head which was discovered two and-a-half years ago. “It’s about the most multicultural object you could imagine from antiquity. This Buddhist head was discovered improbably on the Red Sea shores of Egypt, even more improbably carved in Prokonnesian marble from the Marmara, judging by the drill used for the tortellini curls of the Buddha’s head. It represents, obviously, the Buddha, an Indian holy man whose faith had only just at this point begun to emerge from the north Indian plains, but shown somehow transformed into a sort of Roman solar deity, Sol Invictus. Look at the wonderful sun rays coming out of the back of his head. So, every imaginable eastern and middle eastern and Mediterranean world is converging in this one object.”

For an FT travel piece, he had gone to Angkor Wat in Cambodia. “Reading about something which is put up by an Indian sea captain in an Egyptian temple in the Roman Empire to mark his safe arrival on a ship from Kerala, I realised that there is a story here, the incredible spread of Indian culture.

“We think of these countries as far apart, but using the speed of the monsoon winds, it takes only 40 days to sail from Kerala to the Red Sea coast in Egypt. If you get the winds right, the monsoon winds reverse for the next six months, and you can come back with equal speed. It has meant that Indian sailors on both coasts can propel themselves at speed, first westwards to Egypt and the Persian Gulf, and then from the east coast eastwards to the Malacca Straits and beyond China. So, India is geographically primed to be a major maritime power.”

To Eastern Eye, he made it clear that his book was “a work of history. It’s not a work of contemporary geopolitics. It’s not a political or economic guide to modern India.”

TikTok's future uncertainty sparks competition for top creatorsGetty Images

TikTok's future uncertainty sparks competition for top creatorsGetty Images