NOBODY would today tell the story of post-war migration to Britain without reference to the Windrush.

The scale of attention to this week’s 75th anniversary of the boat’s arrival, at Tilbury Dock in 1948, speaks of its importance as a historic moment. It has become a symbolic ‘origins story’ of both the large-scale Black Caribbean presence in post-war Britain and the broader wave of Commonwealth migration that began this new chapter in the making of a modern, multi-ethnic Britain.

Yet that was not always the case. The meaning of Windrush has shifted from generation to generation. It was the catalytic moment of the 50th anniversary in 1998, marked by a major BBC television series based on a Windrush history by Mike and Trevor Phillips, which brought the story to mass public attention. As Trevor Phillips told IWM’s ‘From War to Windrush 75’ symposium on Saturday, it was not that these stories were not being told, but that there was not yet a significant mainstream attention to them.

This 75th anniversary year is an opportunity to reflect on race in Britain and to deepen the public conversation about our past, present and future. Indeed, the post-war period can be seen as a tale of three quarter-centuries, in which the British experience of race –opportunity and discrimination, racism and recognition – has shifted significantly in each generation.

The first 25 years is the story of the Windrush Generation itself – the contested story of arrival, adventure and expectation, yet also of discrimination and disillusionment. It is a story of racism and of resilience, as those who came as British citizens found that their status was not recognised or respected. It was a sharply contested story – the era of the Windrush Generation, 1948 to 1973, is defined by the end of Commonwealth free movement, once the 1971 Immigration Act built on the gradual restrictions of 1962 and 1968. The Windrush generation had little public voice, even as fierce arguments raged about their presence in the country – whether in the Powellite politics of repatriation, or the more benign response of the first anti-discrimination legislation in the 1960s, passed by parliaments that remained all-white.

The quarter-century from 1973 to 1998 was a different story. Immigration may have been curbed but the emerging diversity of Britain was here to stay. So the first British-born generation began to benefit more from broader opportunities in education, employment and public life, which the sacrifices of the pioneering generation had made possible. There were breakthroughs in national politics, sport, the law, media and other fields. As I reflect on in my book How to be a patriot, it is this generational experience of multicultural advance that informs the broadening-out of identity and opportunity in this period.

Those born in this century will often see things differently. They inherit the progress that has gone before, yet have higher expectations of how the remaining barriers to equal opportunities must be dismantled at pace. The last quarter-century, after 1998, has been a more complex one, of challenge and contestation, advance and retreat. There has never been more black and Asian presence in our public life, yet there is also more polarisation around issues of identity and race.

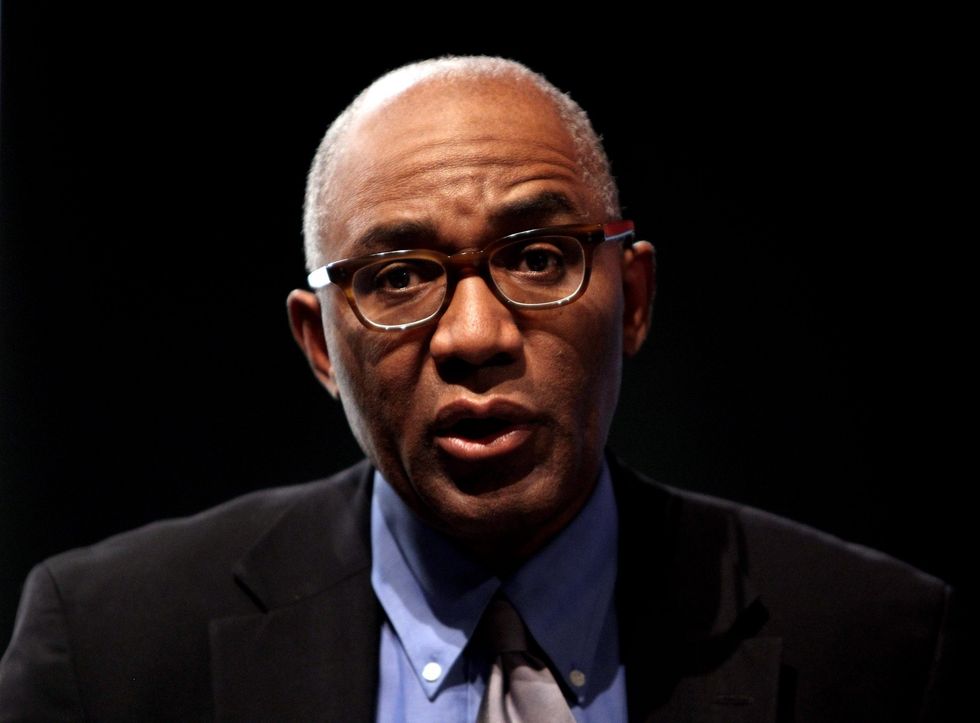

As Kamal Ahmed, of mixed Sudanese and English parentage, reflected at the IWM conference, the experiences of both the first and second generation were, to a significant extent, often shared across black and Asian minority groups. There is both a shared and parallel interest in recording and capturing the stories of the experiences of the first generation before it is too late. The pattern of opportunity and disadvantage has also become more complex. In part the retreat of the overt racism of the 1970s and 1980s made an umbrella identity of ‘political blackness’ less relevant to British Asians by the 1990s. British Muslims came under increased scrutiny and pressure following the 9/11 and 7/7 Islamist terrorist attacks. The Black Lives Matter anti-racism protests of 2020 reflected increasing scepticism among the Black British about the relevance of a ‘BAME’ label, not just because few people from any minority ethnic or faith background are likely to personally identify with such an umbrella term, but because more attention was needed to explore distinct dynamics of opportunity and disadvantage, including the specific challenges of anti-Black racism.

Three-quarters of a century into this story of modern Britain, one lesson of reflecting on the history of race is just how much can change in each generation. The anniversary is an opportunity to express how much of the progress we have made reflects the contribution and resilience of the first post-Windrush generation. The most important legacy would be to look forward as well as back, by renewing our efforts to redeem the full promise of a shared citizenship – by addressing those barriers to equal opportunity, equal voice and equal status in modern Britain that still remain.

Windrush 75 offers a chance to reflect on the history and future of race in Britain

The anniversary is an opportunity to express how much of the progress we have made reflects the contribution and resilience of the first post-Windrush generation, says the expert