THE year 2024 has been deeply sad for Indian music, marked by the loss of some of its greatest artists: Ustad Rashid Khan, Pandit Ramnarayan, Ustad Ashish Khan, and now Ustad Zakir Hussain. The connection to the “golden age” of Indian music is now almost entirely gone.

The loss of Hussain will be acutely felt by many who loved and admired him.

He had achieved celebrity status in the global music world, adding glamour to his performances with his youthful appearance and charisma, charm.

He was fortunate since childhood in having opportunities which others craved. His father Ustad Allah Rakha was already famous as the accompanist to the great sitar maestro Pandit Ravi Shankar. I think it was Ravi Shankar who gave Hussain a huge boost to his career by introducing him and having him accompany his sitar concerts, as indeed Ustad Ali Akbar Khan and Pandit Shiv Kumar Sharma did.

Living in California, Hussain was exposed to a variety of music styles beyond Indian classical traditions. This exposure led him to develop a performance style that appealed to younger audiences, lovers of jazz, and fans of contemporary music. Incorporating Western jazz and African rhythms into his repertoire, he became one of the most versatile Indian tabla players. His career also expanded into acting and composing for films.

Some purists might argue that there are tabla players in India as skilled as, if not better than, Hussain. These artists, while equally exciting and innovative, lacked the opportunities and support Hussain enjoyed. His detractors noted that some of his compositions were learned from other tabla players in India – a fact Hussain himself acknowledged.

I think he was somewhat unhappy that people in India followed musicians outside India, but not the ones in India. They loved and praised fusion music and Hussain was one of the most famous and finest of fusion musicians.

He played in the ‘Punjab’ gharana or style - something that evolved out of the pakhawaj and tabla styles of Varanasi, and, of course, Punjab. So, there was an element of power and technical virtuosity built into his performance, but this lacked the delicacy and emotional performance of the Delhi, Lucknow, Farukhabad and Ajrada table, so much demanded by listeners of solo performance as well as accompaniment.

Hussain acknowledged he could not stop people copying him – his hairstyle, his facial expressions, appearance on stage typically with his mouth open on occasions, his performance content which was slightly removed from the traditional classical tabla playing, but everything the younger generation loved. While he enjoyed all the adulation, he was concerned that tabla playing might get stuck in a certain groove far removed the from its great classical heritage. Some may say he was responsible for taking the tradition away from its heritage.

I first met Hussain formally in 1983-1984, when I sat on the music advisory panel of the Arts Council of Great Britain. ACGB had just formed the Contemporary Music Network (CMN) and its first years programme included a tour by Shakti, led by Hussain with Larry Coryell the great jazz guitarist.

I asked a question in a panel discussion as to whether they considered Indian music to be contemporary or traditional, but did not get any sensible answer.

However, I was asked to do an interview of both Hussain and Coryell at the South Bank Centre in London, where they were to perform later that evening in the Royal Festival Hall. The interview was successful as both were responsive to questions and discussion and were very professional.

Later, I was fortunate to have worked with Hussain, inviting him to UK and Europe with Pandit Hari Prasad Chaurasia, Pandit Shiv Kumar Sharma, and, of course, his famous group Shakti and Remember Shakti.

The Asian Music Circuit was commissioned by the BBC to produce a concert of Remember Shakti in Mumbai, which we did successfully. The concert tours in the UK were hectic, often involving travelling between venues in “sleeping coaches”, resulting in concerts on consecutive evenings up and down the country. The stamina needed was phenomenal, but the musicians relished the experience.

When Ustad Allah Rakha passed away, I organised a meeting at the Bhavan and also to speak there in his honour. Hussain also attended. I quoted a passage from the Bhagvad Gita, which invited us not to grieve for something that has not perished. The soul may have left the body it had occupied for some years, but had finally left it and moved on its journey to join the universal soul and conciousness. Hussain is on his way to join the universal soul and will live on in our memories and in the vast body of work he has left behind in films, recordings and friendship.

I send my most sincere condolences to his sister, Khurshid Auliya and her husband Ayub, and to his brothers and wider family in India and around the world. We pray to the Almighty and that his soul will rest in eternal peace.

Viram Jasani is the former Chairperson and CEO of the Asian Music Circuit

Sonia Sabri Certain Blacks

Sonia Sabri Certain Blacks Sonia SabriCertain Blacks

Sonia SabriCertain Blacks

Himali Singh Soin and David Soin Tappeser

Himali Singh Soin and David Soin Tappeser Kinnari Saraiya

Kinnari Saraiya The Transformation (2024)

The Transformation (2024)

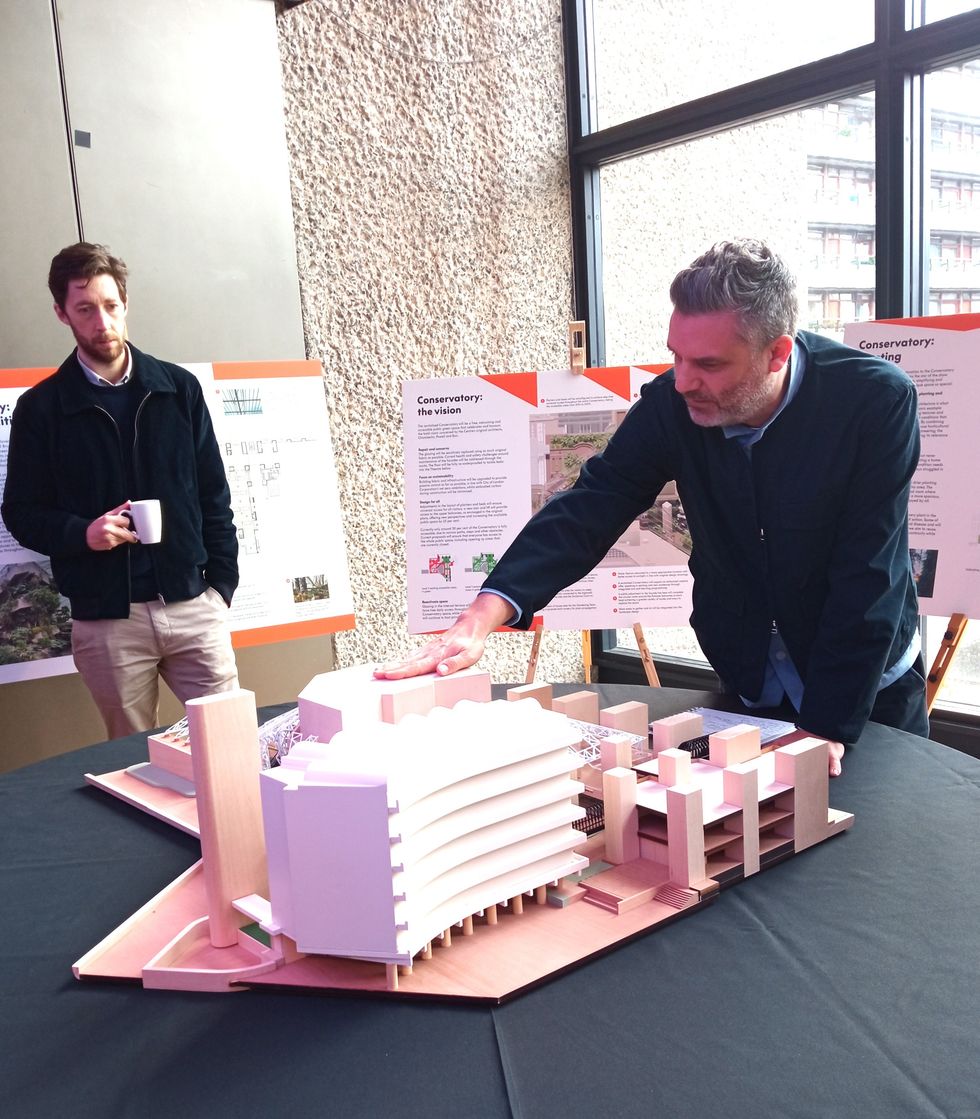

Oliver Heywood during planning discussions

Oliver Heywood during planning discussions The Lakeside Terrace

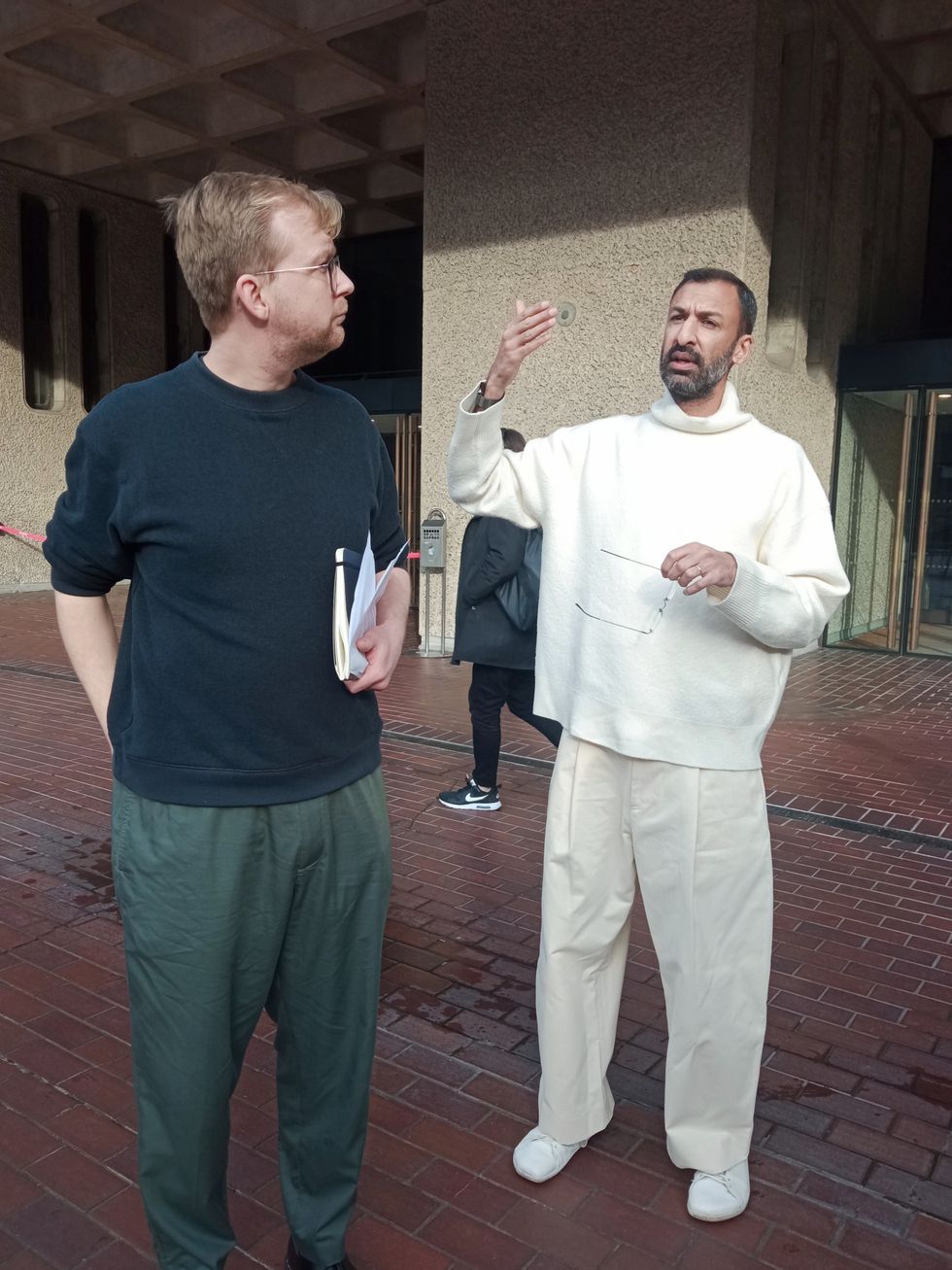

The Lakeside Terrace Asif Khan (R) with colleague Alex Watt

Asif Khan (R) with colleague Alex Watt The Conservatory

The Conservatory

Chowdhry on stageOMJ Photography

Chowdhry on stageOMJ Photography